Vol 2 (2019), No 2: 60–89

DOI: 10.21248/jfml.2019.14

Smartphone-Based Language Practices among Refugees:

Mediational Repertoires in Two Families

Abstract

This paper explores how refugee families in Germany draw on mediational repertoires to accomplish a range of digital literacy practices on their smartphones. We introduce the concept of ‘mediational repertoire’, i.e. a socially and individually structured configuration of semiotic and technological resources for communication, and use it in an ethnographic case study with participants from Syria and Afghanistan in a refugee residence in Hamburg in 2017/18. The collected data includes nine semi-directed interviews, video demonstrations of smartphone usage, and ethnographic fieldnotes. Qualitative analysis draws on mediagrams, i.e. visualizations of mediational repertoires in two families. Findings suggest that individual mediational repertoires in these families differ especially by generation and other factors, such as literacy competence, type of social relationship and purpose of online use, including smartphone-based language-learning.

Keywords: linguistic repertoires, mediational repertoire, polymedia, refugees, smartphone-based language practices, informal language learning

1 Introduction

In 2015, approximately 890.000 refugees, mostly from Syria, Albany, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq, were registered in Germany (BAMF (2016); Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat (2016)). Media reports from this period repeatedly discuss smartphone usage among refugees, and the image of newcomers who seemed to enjoy apparently easy access to mobile devices sparked outrage among certain segments of the German society. Here are some headlines and excerpts from these media stories:

Handys sind für Flüchtlinge kein Luxus

‘Cell phones are not a luxury item for refugees’

(Sueddeutsche.de, 11.08.2015)

Das ist der Grund, warum so viele Flüchtlinge ein Smartphone haben

‘That is the reason why so many refugees have a smartphone’

(Focus.de, 12.08.2015)

Warum so viele Flüchtlinge mit

ihren Handys auf dem Marktplatz zu sehen sind.

‚Ich kann mir kein Handy leisten; die Asylanten haben fast alle eins und hängen

wie die Chefs telefonierend den ganzen Tag auf dem Marktplatz rum.‘

‘Why are there so many refugees with their cell phones on the market square?’

“I cannot afford having a cell phone; most of the refugees possess one, they hang out on the market square phoning as if they were some kind of boss”

(Remszeitung.de, 24.09.2015)

Viber, Xavier und deutsches Gemüse. Was haben Flüchtlinge auf ihren Smartphones? Welche Apps mutzen sie? Und welche Bedeutung hat das Handy?

‘Viber, Xavier and German Vegetables: What’s on refugees’ smartphones? What Apps do they use? What do cell phones mean for them?’

(Spiegel.de, 12.05.2016)

Some media stories of this sort focused on the disapproval of ‘luxury items’ possessed by refugees, given their price and non-affordability for many Germans. Other media stories feature interviews with refugees and explain the various functions mobile devices fulfill for them, including digital storage of identity documents and photos, machine translation, learning German, and gaining orientation in the new country. However, given the diversity of asylum-seekers in terms of their linguistic repertoires, educational biographies and socio-economic status, premature generalizations about their digital media use seem problematic. Our starting point for the pilot study reported in this paper is therefore the assumption that refugees’ digital media practices are closely related to their multilingual repertoires, on the one hand, and the process of their (linguistic) integration into a new social environment, on the other. In this paper, we focus on two explorative research questions: First, how is smartphone usage by asylum-seekers related to their linguistic choices in written or spoken language? Second, how does their smartphone usage relate to informal learning of German?

This paper is organized as follows. We first discuss research findings on the interdependence of forced migration and digital media, and introduce the notion of mediational repertoires (section 2). We then outline our fieldwork, access to data (section 3), and technique of visual representation of mediational repertoires (section 4). Against this backdrop, a detailed analysis of the mediational repertoires of two asylum-seeking-families from Syria and Afghanistan is provided (section 5), followed by findings on informal language-learning practices by our informants (section 6). We conclude by summarizing our findings and exploring possibilities for further research (section 7).

2 Smartphones, mediational repertoires, and informal learning

Unlike media stories, academic research on how asylum-seekers and forced migrants use their smartphones is still scarce. Harney (2013) carried out research on how African refugees in Italy use their mobile phones and emphasizes their dual function of connectivity and self-protection from potential risk such as police raids. Wall et al. (2015) carried out qualitative interviews with Syrian refugees in a Jordanian camp. Their findings show that smartphones are their key medium to deal with the information precarity on the camp. Smartphones enable refugees contact to left-behind family members, access to relevant information, cues to assess uncertain information, and access to their own representation in the media. To avoid being surveyed and to protect their relatives and other addressees from being prosecuted by Syrian authorities, these informants reported using coded language in their smartphone messages (Wall et al. 2015: 11). In another ethnographic study, Jacquement (2017) examines how refugees use smartphones after their arrival in Italy. One important function is in the juridical process, where an applicant’s status as an asylum-seeker is being determined in court. Refugees draw on documents saved on their smartphone and video clips they recorded on their refuge route in order to prove their identity claims. They also use their smartphones as evidence for claims of cultural ethnic or religious belonging (e.g. symbols used as background images or other saved materials), and the translation function is also important before court and elsewhere.

In a three-year ethnographic study on media practices of asylum-seekers in Germany, Witteborn (2015) explores the processes of information sharing, transnational grouping, and political learning that her informants pursue online. She finds that computers and mobile phones were highly important for the refugees in order to establish connections, for job-seeking, dealing with daily routines of schooling and health care, and maintaining socio-cultural and religious networks and family communication outside Germany. In contrast to the present-day situation where refugees’ media practices are highly focused on smartphones, Witteborn’s fieldwork from 2011 to 2013 documents the importance of computers in the accommodations, whereas mobile phones were still expensive and unavailable to refugees due to their unstable stay permit. Witteborn (2015: 352) also mentions that around forty percent of her informants used Skype and almost fifty percent used Facebook, thereby exploring the opportunities of these media to present themselves in ways that downplayed, or indeed erased, their stigmatized asylum-seeker status, highlighting instead other identity aspects (Witteborn 2015: 357–358).

A main finding of these studies, which also holds true for our informants, is the importance of mobile devices at various stages of the refuge and asylum-seeking process. For example, one informant told us that map applications on mobile phones were the only opportunity they had to verify the claims of the human trafficker regarding their current territory. Should a trafficker attempt to deceive them by saying they were already on Greek soil, a map application with GPS tracking was the only way to verify this. Some of our informants also report that after having secured asylum in Germany, smartphones remain crucial for a variety of purposes, including language learning, contacting people from one’s own community, and receiving news from their homeland. There is a remarkable overlap here between these few studies and research on transnational family communication among migrants, which also suggests digital media have become indispensable tools for transnational family lives (Thomas/Lim 2010: 188; Madianou/Miller 2012). The insight that polymedia (i.e. the availability of various media channels for interpersonal communication) transform the experience of migration (Madianou 2014) seems therefore valid for refugees and asylum-seekers as well.

From a sociolinguistic viewpoint, such extreme cases of forced transnational displacement highlight two key points about language in the context of global social mobility. First, they reinforce the suggestion that language practices are a key resource for digital literacy (Jones/Hafner 2012). This suggestion is not limited to specific languages, such as Arabic or German, but to languaging, i.e. communicative practices by which speakers (and writers) draw on their linguistic repertoire for purposes of meaning-making (cf. Madsen et al. 2016). Language practices are crucial to both key dimensions of mobile communication: human-computer-interaction (i.e. practices of interactivity with the digital device) and human-to-human interaction (i.e. digitally-mediated interaction with human interlocutors in spoken or written language). In both, language is bound by the affordances and constraints created by smartphones (Hutchby 2001; Bucher/Helmond 2018) at the level of hardware and software. In other words, the ways smartphone users deploy their linguistic resources is closely related to the design of the device itself (e.g. the size of its keyboard and screen, which create conditions for typing and reading or watching) as much as to the design of the software applications they might decide to install on a device (each application enables particular communicative practices, but not others).

A second key point about language and digital connectivity is the flexibility of linguistic repertoires under conditions of intense (forced) mobility. Recent sociolinguistic scholarship suggests that transnational mobility and digitally-mediated communication may impact on individual linguistic repertoires in diverse ways (Androutsopoulos/Juffermans 2014; Deumert 2014; Blackledge/ Creese 2017). Linguistic repertoires become more flexible, less constrained by community norms and traditions, more individualized, and more fragmented. They are constantly enriched by (fragmented) resources, which may originate in the global circulation of digital content and exchanges or in the spatial trajectories that people move through (Androutsopoulos 2014; Blommaert/Backus 2013; Busch 2015). Taking this to the present study, we ask whether smartphone-based language practices in conditions of forced migration are characterized by repertoire stability or rather fluidity and growth. In the present case, such growth is especially related to the role of German, the majority language that forced migrants are confronted with and under pressure to acquire in order to move on in the new country.

To examine the close and complex relationship between language practices and the technological conditions of digitally-mediated communication, we draw on the notion of ‘mediational repertoire’, recently developed by the second author in research on multilingual digital communication in migrant families (Lexander/ Androutsopoulos 2019; Androutsopoulos/Lexander, subm.) This notion pulls together the concepts of linguistic repertoire (discussed above) and mediational means (Scollon 2001). Scollon’s notion of mediational means posits that all communicative action is mediated, and that “mediated action is carried out through material objects in the world (including the materiality of the social actors – their bodies, dress, movements) in dialectic interaction with the habitus” (Scollon 2001: 4). Adapting this to interpersonal communication, a mediational repertoire can be thought of as a socially and individually structured configuration of semiotic and technological resources that are available for communication. It comprises modalities of language (speaking, writing, or signing), sets of digitally-available, pre-figured pictographic and multimedia signs (e.g. emojis, memes, animated gifs, video clips), and sets of software applications (e.g. smartphone apps such as WhatsApp or Telegram), as well as patterned co-selections of linguistic and media resources to conduct communication to particular (types of) addressees. A mediational repertoire can thus be thought of as an augmented, or extended, approach to a linguistic or semiotic repertoire, an extension that seems necessary in view of current communicative practices. When people communicate via smartphones, their linguistic choices pattern together with their choice of software apps. Examining languages in isolation therefore becomes increasingly meaningless. What is important to people’s digital communication is, first, the range of semiotic sign-sets they have at their disposal (including additional signs besides typed-in ones, such as emojis, gifs, memes, which are weaved together with linguistic signs into language-based utterances), and, second, a range of software applications which, once installed and ‘opened’, provide a grid for interactivity (e.g. Google maps) and interaction (e.g. via WhatsApp). The figures presented below, ‘mediagrams’ (cf. section 4), are a technique that aims to represent visually such multi-faceted patterns of language, modality and media choice for interpersonal interaction and human-computer-interactivity.

Part of our approach in this paper is to examine relationships between smartphone-based practices and informal language learning in post-refuge conditions. Sociolinguistics scholarship on repertoires (notably Blommaert/Backus 2013) theorizes informal learning as a key impact on the dynamic structure of linguistic repertoires in a globalized world. We suggest this holds true for forced-migration processes as well, where language-learning is often fragmented and transient. People might learn a few words in the local language to get by while attempting to move on. However, once the opportunities to settle are given (for example for Syrian asylum-seekers in Germany), language learning becomes of paramount importance. As discussed in the empirical part of this paper (see section 6), our informants draw on various smartphone-based activities for learning German, such as YouTube language tutorials or machine-translation interfaces such as Google Translate. Indeed, even the setting of people’s language preference on their smartphones could be considered a learning activity. For example, using a certain app in the German language due to the lack of an Arabic version is a necessity, which increases exposure to German on a regular basis. Using German language apps can therefore be considered an outcome of language learning, but also itself a part of the learning process.

Research on such digital practices of informal language-learning by forced migrants/refugees seems non-existent at the completion of this paper. We therefore briefly turn to educational research on learning with technology outside the classroom, or mobile learning. Nunan/Richards (2015) present a range of case studies on out-of-class language-learning, including Internet learning and learning through TV, which are considered important pedagogical resources for autonomous learning. Demouy et al. (2015) examine how distance learners use a range of smartphone apps for learning activities such as watching videos in the target language. All informants attended a regular language-learning class as well and used mobile learning as an addition to their formal training, thereby reporting a gain in autonomy and access to authentic speech patterns through smartphone-based learning activities. Lai/Zheng (2018) study a group of university-level language-learners and identify three dimensions of mobile language-learning outside the classroom: personalization (i.e. creating a personalized learning space), authenticity (i.e. access to authentic materials), and connectivity as an actual interactive practice. Chik (2018) explores practices of out-of-class learning by which people carve out time in their daily routine for learning a foreign language. She investigates foreign language acquisition within Stebbins’ concept of ‘serious leisure’ (Stebbins 1994, 2015). Drawing on a study of the self-managed out-of-class learning of three students at the undergraduate level, Chik highlights several paths of independent, personalized language learning and links them to the affordances of various digital spaces such as online gaming, reading news, watching series, and participating in social media communities such as Flickr and YouTube (see also Barton/Lee 2013). Generally speaking, the learners of the out-of-class language training are free to design and manage their “portable learning space” in a highly individualized and therefore unpredictable way (Chik 2018: 57).

A number of similarities can be identified between this research and our field observations and findings (see section 6), and general parameters such as personalization and authenticity are clearly also valid for the ways in which refugees manage access to digital content for learning purposes. However, educational research on mobile learning is designed in ways that are not entirely transferable to forced-migration and post-refuge contexts. In particular, mobile learning is often considered an additional and therefore complementary way of learning a foreign language, and an outcome of this research are indeed suggestions on how to adjust in-class teaching material. The learners interviewed in these studies refer to mobile learning as a leisure activity, which often offers interaction and entertainment. Among forced-migrants, however, smartphone-based language-learning is only partially a complement to institutionally supported language (or so-called ‘integration’) classes. Rather, learning materials on the Internet are sometimes the only available resource for language-learning, and learning activities are thus entirely unguided by local institutional actors. We return to these issues in sections 3 and 6 below.

3 Explorative ethnography and data collection at a residence site

This paper is based on explorative ethnography carried out from August 2017 to January 2018 in Hamburg, Germany’s second largest city. It involved participant observation in an asylum-seeker residence site that was mostly used by families with children. Access to the field was enabled through the first author who volunteered to teach a German-language class to adult residents on the site. The site residents come from various countries and continents, but most participants in the German course offered by the first author were from Syria and Afghanistan. The course was offered for six months and was attended each week by four to ten residents with various fluency levels in German. Active observation was therefore possible at two sites, i.e. within the classroom where the German class was held and on the residence site as a whole, which comprises several apartment buildings, a shared leisure time room and shared laundry room.

All class participants were adult learners who either had no legal claim to attend an official integration course[1] due to stay permit restrictions or were waiting for their integration course to start in the future. This learner group was highly diverse in many regards. Some participants (like Omar, discussed below) were largely illiterate, some could read but not write, and some were literate in several languages. These varying degrees of literacy were closely related to participants’ widely differing educational biographies. Some had never attended any type of school, some had to quit school at some point due to economic or political reasons, others had completed some type of professional training. Most participants could speak several languages and dialects from their respective home country as well as (fragments of) languages they acquired on their forced-migration route. Some were competent in foreign languages such as French or English. However, as the teacher of the volunteering German class (i.e. the first author) does not speak any of the residents’ first languages, most classroom interaction involved some form of translingual practice (Canagaraja 2013), which included features of German, English, Arabic, Farsi, Pashtu, and Kazakh. The last one, which happens to be the first author’s second language, shares some common lexis with some Farsi dialects and therefore was a useful asset for building a trustful relationship within the group. In addition, classroom communication was facilitated by the students’ and teacher’s mobile phones, which were regularly used to search for specific terms, pictures, translations and even socio-historical and political facts. For example, the celebration of Reformationstag[2] was used as an occasion to discuss with students the impact of Protestant reformation on modern European societies.

The refugees’ situation in terms of internet access was precarious. There was no freely-accessible internet access or WiFi on the entire residence site, nor was a computer room available. Most residents therefore depended on wireless access spots in cafés and other public places in order to visit social media platforms and use web-based applications. Most asylum-seekers on the residence site had a mobile phone, most commonly a smartphone, which they all used frequently.

Brief conversations with site residents at the start of fieldwork quickly revealed that mobile phones are indispensable communication tools for all basic ‘migration needs’. For example, the residents learn German online with the help of various apps. They rely on Google maps and similar online map services to gain orientation in their new urban environment. They search the web for jobs, doctors, and permanent accommodation. They use phone or WhatsApp calls and messages to communicate with state authorities, lawyers, and their children’s schools, as well as to stay in touch with family members and friends in their home countries and worldwide, and to create new contacts in Germany. Not least, they use their cell phones for emergencies. These communicative practices are not entirely specific to recent asylum-seekers. Rather, the overall impression gained from ethnographic fieldwork is that site residents perform the same activities on their phones as many other migrant groups do. However, one important difference here is the fact that non-permanent resident status makes it very difficult to open a cell phone contract in Germany. As long-term mobile phone contracts require proof of permanent residence, most residents rely on overpriced pre-paid SIM cards they buy in call shops or supermarkets. Most of the residents find themselves in this precarious situation, experiencing a high pressure to integrate socially and linguistically, while not having stable means of communication.

|

Pseudonym |

Gender |

Country |

Age |

Stay in Germany |

|

|

1 |

Ebrahim |

M |

Afghanistan |

17 |

3,5 |

|

2 |

Sarina |

F |

Afghanistan |

56 |

4 |

|

3 |

Omar |

M |

Syria |

52 |

3 |

|

4 |

Elayla |

F |

Syria |

17 |

4 |

|

5 |

Kadira |

F |

Syria |

44 |

4 |

|

6 |

Sabira |

F |

Syria |

25 |

2 |

|

7 |

Yusuf |

M |

Syria |

48 |

3,5 |

|

8 |

Mustafa |

M |

Syria |

36 |

5 |

|

9 |

Miran |

M |

Afghanistan |

15 |

2 |

Table 1: Informants’ data

Three types of data were collected during this six-month ethnography, i.e. ethnographic fieldnotes, guided audio interviews, and short video recordings of selected informants who demonstrated their mobile phone usage. Fieldnotes include the ethnographic descriptions of the observations on site and in the classroom. Guided interviews were carried out with nine informants, i.e. five males and four females, three from Afghanistan and six from Syria (see Table 1).

The age of the informants varies from 15 to 56, three are school students (Ebrahim, Elayla and Miran).[3] Two informants highlighted in grey (Sabira and Miran) were recruited outside the accommodation: They are friends of the interviewed residents. The average stay of the informants in Germany on the time of the interviews was 3 years. Interviews’ topics covered the informants’ linguistic repertoires, their media usage in Germany and their homeland, their communication networks and language choice, and language-learning practices. At the end of each interview, informants were asked to demonstrate the smartphone apps they use most frequently in their current daily routine.

4 Mediational repertoires and mediagrams

To represent relationships between language and media choices in our informants’ smartphone-based practices, we draw on a visualization technique termed ‘mediagram’ (Lexander/Androutsopoulos 2019). A mediagram is a visual representation of the co-patterning of language, language modality and media choices in digitally-mediated communication. The idea and term are inspired by sociograms, a social network visualization method (Hoang et al. 2006) that has been widely adapted in sociolinguistics for research on linguistic variation and change (Sharma 2017). Similar to the use of sociograms in social-scientific research generally, mediagrams are a graphical representation of qualitative data aimed at making patterns visible and at presenting information during the data-gathering process (Huagan et al. 2006; Tubaro et al. 2014). The design of mediagrams orients that of sociograms for ‘ego’ networks (or personal networks), which represent social relationships between a core informant (ego) and relevant partners (alters) by means of a circular layout and ‘ego’-centered graphic pattern (Sharma 2017). However, mediagrams differ from other versions of sociograms in the kind of information they represent and the graphic means deployed to this aim. Their main focus is on networks of communicative connections enabled by mobile devices. Shapes, layout, and color are deployed to represent different languages, language modalities, and mediational tools (i.e. software apps).

For the purposes of this paper, mediagrams are compiled based on information reported in the interviews in order to represent the following types of information. Based on a circular layout, each informant is represented in the center of a mediagram, their interlocutors (as reported in the interview) radiating in distinct nodes. Our scheme distinguishes between Germany-based interlocutors and those abroad. All addressees are identified by their social relationship to ego and their country of residence, if abroad. Against this backdrop, colors and layout structure are used to represent language choices: each reported language is given one color, and all languages reported by an informant are arranged in a pie graph around the ‘ego’ node, with the size of each slice signifying the importance of each language in the interviewees’ report about their smartphone-based language practices.[4] However, our data are not sufficient to provide deep insights into how our informants experience each language in their repertoires; additional narrative interviews would be required to this purpose. Each ‘ego’ is connected to all reported interlocutors by lines, with line type signifying reported modality of language: continuous lines are for written, dotted ones for spoken language use, and a ‘Morse’ pattern means both modalities are being used in a particular dyad. Each application is represented by its respective (trademark) icon. Non-interpersonal practices, where our informants interact with software rather than with other humans, are listed separately and also coded by language choice.

5 Smartphone-based mediational repertoires in two families

The following mediagrams, based on the guided interviews, summarize the interdependence of three key notions: language selection, medium/program selection and the addressees. In order to explore this interdependence, two families of different origins were selected: one Syrian and one Afghani family. Our analysis explores the complexity of their language acquisition and general integration processes practiced on smartphone. Our decision to interview families rather than individual users was motivated by the chance to explore the role of older children and adolescents in refugees’ communication practices. Most of the parents in these families were not fluent enough in German or English to participate in the interview, therefore their teenage children translated and explained our research goals to their parents and helped to set up the interview appointments. As in many other migrant families, teenage children mediate between their parents and various institutional authorities (school, doctors, migration office), and even act as German language trainers to their parents. Therefore, studying refugees’ language and media practices ought to take into consideration the family networks adult refugees rely on in order to get by in their new sociolinguistic environment.

5.1 The Syrian family

The Syrian family consists of father, Omar, mother, Kadira, and daughter, Elayla, who was a high-school student during fieldwork. Elayla also acted as an interpreter in her parents’ interviews. This family has lived in Germany for four years.

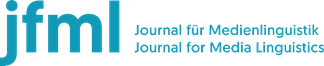

Figure 1 shows Omar’s mediagram. His meditational repertoire is quite distinct compared to all other informants considered in this paper. Most of the practices he performs on his phone are carried out in spoken Arabic. His preferred software apps are regular phone-calls and WhatsApp, which he also uses to do phone calls. This limitation is explained by Omar’s educational biography, more specifically the fact that he only had three classes of school education and therefore has great difficulties reading. Regarding Omar’s learning of German, his daughter, Elayla, reports that her father used to have a phone application for learning numbers and letters, which he however stopped using after a while. Elayla explains some strategies Omar uses in his daily communicative routines while in Germany. (All excerpts are presented in English translation, see appendix for original excerpts and transcription conventions).

Excerpt (1): Omar (interpreted by Elayla)

218: E: He can write in Arabic • but very little • and also when he writes, he makes mistakes • he knows many streets even though he cannot read the name of the (bus/train) station properly • but when he hears its name pronounced and he sees one thing in that street • then he can keep it in his head • therefore he knows a lot of streets in Germany this way • even when I’m looking for a doctor’s office for example • and I say let’s google it • he says • just follow me, I know the address • he’s got a kind of computer in his head

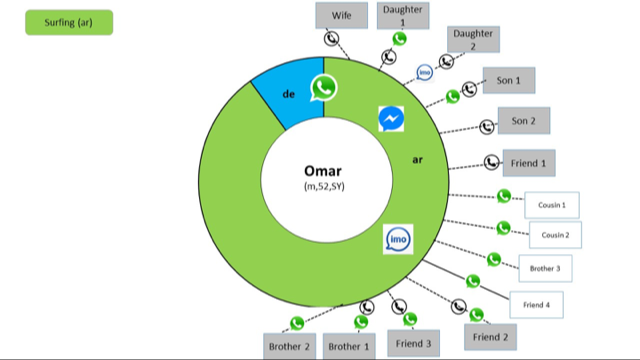

Unlike her husband, Kadira has a broader meditational repertoire (Figure 2). One of its most distinct features in her mediagram is the range of German-speaking interpersonal contacts. Kadira mentions at least six contacts in the interview, two of which, namely a teacher and her mentor, are external to the residence site. Kadira also communicates in German within her two sons and her daughter, Elayla, who explained in her interview that she puts pressure on her mother to actively use the German language (see below). Kadira also speaks English, which is explained by the fact she attended school for 11 years and has a higher literacy level.

Excerpt (2): Kadira (interpreted by Elayla)

178 E: in contrast to my father, my mother is always online • she surfs online because she can read better than he does • she can read both German and Arabic very well, but he can’t, therefore he cannot do that much on the Internet

Kadira also learns German on her phone with the help of her children. Her daughter, Elayla, reports that her mother learns German online every day for at least one hour. Kadira also uses German to surf the web and translate from Arabic to German via Google Translate. She highlights the importance of this ability when it comes to a critical situation such as a hospital emergency:

Excerpt (3): Kadira (interpreted by Elayla)

36 E: my mother wants to say, that she had been alone in the hospital last week and that she had used this program [Google Translate], so that the doctors could understand her well.

Figure 1: Omar’s mediagram

Figure 2: Kadira’s mediagram

Like her husband, Kadira prefers the spoken mode and WhatsApp. She also uses other apps such as Facebook, SMS-Messaging, Viber, and Imo, which are not part of Omar’s repertoire. Kadira touches in her interview upon the lack of wireless internet access on their accommodation site, emphasizing the importance of internet access for her younger children’s language-learning:

Excerpt (4): Kadira (interpreted by Elayla)

340 E: She says, that she finds it bad that we do not have the internet at home and that we cannot use YouTube for learning German. My younger brothers also want to watch the children series in German, but they can’t because we don’t have any internet.

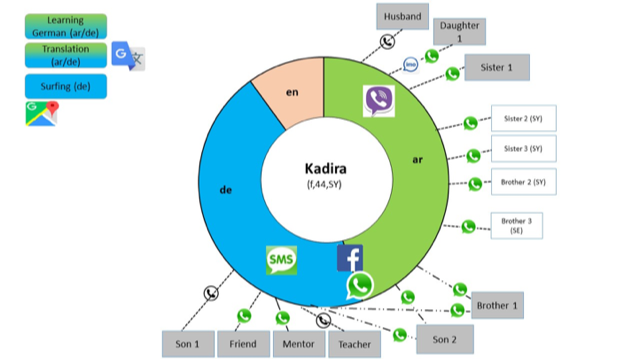

As for Elayla, one obvious characteristic of her mediagram (Figure 3) is that she has almost no contacts outside of Germany. An exception to this are her friends abroad whom she stays in contact with via Facebook, thereby using English as a lingua franca. These are mostly people she met on her way to Germany. Elayla’s linguistic repertoire is more diverse than that of her parents. She speaks German, English, Arabic, Kurdish, and Turkish at different proficiency levels. It is remarkable that even her family language had become German, which she reports as being one of her two most frequently used languages along with Arabic. She even tries to use some German with her father, whose German knowledge is quite limited. Besides German, she uses Arabic and English in both the spoken and written mode.

Elayla is enrolled in a German high-school (Gymnasium) where she has to communicate in German to her teachers and classmates. She expressed a high commitment to improving her German, which she prefers to other languages in her linguistic repertoire. In the extract below, Elayla refers to her preference of German in her interaction with an Arabic-Kurdish speaking friend of hers.

Excerpt (5): Elayla

164 E: She is a best friend of mine. And we always write each other messages over WhatsApp. We speak German. And I send her a lot of written messages. She can speak Kurdish and Arabic. But we only speak German. So that we don’t make our German worse.

Along with German and English, which are mandatory language-subjects at school, Elayla also learns Turkish, which is offered as a foreign language along with French and Spanish. Her interest in this language was raised long before coming to Germany:

Excerpt (6): Elayla

17 E: I can speak a bit of Turkish. And I can also understand it, but I cannot read and write it. I can sometimes use it. […] I’ve learned a lot of Turkish songs and I keep singing them all the time. When I was in Syria, my sister and I used to watch a TV series in Turkish. Well, dubbed in Arabic.

Figure 3: Elayla’s mediagram.

Remarkably, Elayla’s mediagram includes some apps that her parents don’t use, namely email and Instagram. Being a student, Elayla must have an email account in order to send and receive school documents and weekly assignments. Instagram, on the other hand, is one of the most popular social media platforms in Elayla’s age group. Elayla also uses her smartphone for watching videos and movies in Arabic, and surfs the Internet in two languages, German and Arabic.

Summing up, this Syrian family shows a wide range of smartphone-based practices with clear intergenerational differences. All three family members use their smartphones to browse the web, look up information, keep up contact with other people, entertainment (e.g. watching videos), and various language-related practices such as everyday-purpose machine translation and learning German. While both parents are mainly limited to the use of one (Omar) or two (Kadira) languages and a strong preference for the spoken mode, the daughter displays a multilingual repertoire, which is shaped by her forced-migration experience (friends in Turkey) and her media practices (e.g. Turkish series, Facebook communication in English). While both parents actively maintain contact to family members who remained in Syria, Elayla does not maintain any contacts to Syria, perhaps due to her young age of forced migration. Omar’s case exemplified the close relationship between illiteracy and smartphone usage, especially when it comes to metalinguistic practices and more specifically language learning. Having had only three classes of school education, Omar strongly prefers spoken-language applications and avoids text-messaging.

5.2 The Afghani family

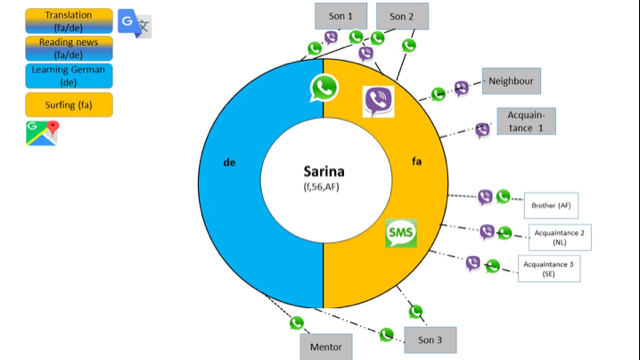

The second family consists of mother, Sarina, her son, Ebrahim, and two more sons who were not interviewed. The family has been in Germany for four years. Ebrahim attends high-school and Sarina stays at home.

Sarina speaks Farsi and learns German in a class offered on the accommodation site. Most of her communication is performed in Farsi. Like the Syrian parents discussed above, Sarina remains in contact with her family and acquaintances abroad. Some of them still live in Afghanistan, others have migrated to other European countries, e.g. Netherlands or Sweden. Sarina uses two main apps, WhatsApp and Viber, for most of her media interactions, thereby both speaking and writing. In her interview, Sarina told us she installled Viber long before WhatsApp and keeps using this app out of convenience. To communicate with her sons, Sarina draws on both German and Farsi. Her only German-speaking contact is her mentor, an elderly German woman, who helps her buy groceries and gain orientation in Hamburg. The mentor communicates with Sarina only through WhatsApp text messaging. Along with the German courses offered by the first author on the resident site, Sarina also learns German online (see section 6).

Sarina also reads the news in both languages and uses Google Translate, the machine translation app, on a daily basis. When surfing the Internet, Sarina also uses both languages interchangeably. She loves to watch YouTube cooking shows in Farsi and to then try out the recipes. Sarina also showed us a smartphone application called “Muslim Pro” which Muslims use for conducting their prayer sessions.[5] It provides information about prayer times and draws on the smartphone user’s GPS (geo-positioning coordinates) to identify the position of Mecca. It also offers some prayers in Arabic, transliterated into the Latin alphabet with a German translation.

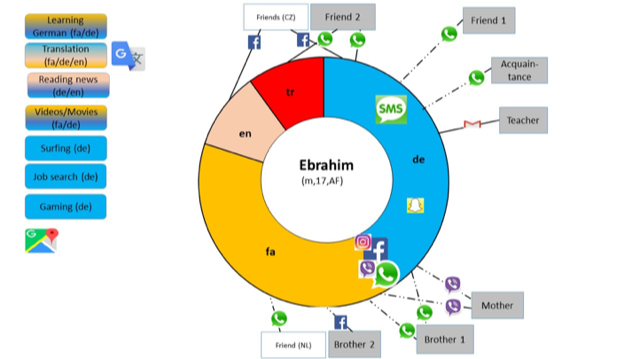

Sarina’s son, Ebrahim (Figure 6) was 17 years old during fieldwork. His linguistic repertoire includes Farsi, German, Turkish and English, with German and Farsi being his most frequently-used languages. WhatsApp is the app he uses most. Ebrahim uses certain apps for communication with particular speakers. For example, he uses email for communication with school teachers, while Viber is reserved for interaction with his mother.

Figure 4: Sarinaʼs mediagram

Figure 5: Ebrahim’s mediagram

Like Elayla, Ebrahim’s mediagram is more diverse and complex than that of his mother. Not only does he speak and write more languages and uses more apps, but he also maintains more contacts in his daily communication. Like Elayla, Ebrahim maintains no contacts to Afghanistan, his country of origin. His connections abroad are friends in other EU countries (Netherlands and Czech Republic), which he mostly contacts via WhatsApp or Facebook. Both Elayla and Ebrahim use Facebook for communication with friends abroad and do so mainly in English. Ebrahim’s repertoire also includes Instagram, where he uses both his main languages, German and Farsi. Additionally, Ebrahim mentions Turkish as one of the languages he uses on WhatsApp with one of his friends in Germany:

Excerpt (7): Ebrahim

47 E: I can understand Turkish a bit and I can also speak some. Not a lot. I learned it from my classmates. In my class there are 24 students and 18 of them come from Turkey. That is why. They taught me the languages a bit.

Unlike Elayla, who gained interest in Turkish through her fondness for Turkish soap operas and learns standard Turkish as a foreign language at school, Ebrahim experiences spoken Turkish in his direct surroundings and thereby learns bits of the language informally. Some of his classmates have a second- or third-generation Turkish background and are Turkish/German bilinguals. Ebrahim did not attend an ‘integration class’ at the time of fieldwork.[6] He learned German on his smartphone, has now successfully passed that stage and attends regular school classes. In the following excerpt, Ebrahim reports about his first experience in a German school while attending the German integration class.

Excerpt (8): Ebrahim

185 E: On the first day of school my teacher got disappointed. All the students had to start with the ABC and I could already speak some German. She asked me why I could speak so well. At that point I had been in Germany for two months. I told her that I had learned German by myself but without any grammar.

Some of Ebrahim’s smartphone routines are monolingual (in German), e.g. online-gaming, job and apartment search, while others are bilingual (in German and Farsi) such as learning German, doing translations, reading news and watching videos or movies. Being the most competent speaker of German in his family, Ebrahim is responsible for all communication with relevant institutions. He also has a part-time job, which he mainly arranges via phone communication:

Excerpt (9): Ebrahim

117 E: Because I work part-time in a hotel, my boss calls me and I also have to call him back. I also have to arrange multiple appointments on the phone for my mother. For her doctor appointments or some apartment offers that we receive. We always have to contact them on the phone to confirm the appointment.

To sum up, we see several similarities in both families’ linguistic and media practices. The parent generation maintains consistent contact with relatives and friends in their countries of origins, whereas the children’s main communication partners are located in Germany, and while the parents stick to smartphone software they are already familiar with, their teenage children explore a variety of new apps. An important difference between the parents and their children is their competence in German. Elayla and Ebrahim became literate in their first language in their respective home country, learned English at school in their home countries and now attend the German school with mandatory German as a Second Language courses. Their exposure to languages and literacies is much greater than that of their parents, and their fluency in German is prompted by a number of German-speaking friends and acquaintances they interact with, while their parents’ communication is mainly limited to their monolingual community (both at the residence site and online). With their competence of German, the children arrange appointments for their parents and search for jobs and apartments. Most of these activities are carried out on the phone in spoken German.

6 Learning German on the smartphone

The discussion so far indicates the importance of smartphones for language-learning practices among our informants (and asylum-seekers generally). Learning German in the context of seeking asylum is not ‘leisure time’, but a necessity that is nurtured by real demands. Similar to educational research reviewed in section 2 (Chik 2018; Demouy et al. 2015), our informants organize their learning in a highly autonomous way in terms of time, place and content. However, unlike the learners studied in educational research on mobile learning, most of the adult asylum-seekers in this residence (excluding the students and adults who attend so-called integration courses) are not entitled to paid-for German language courses. Therefore, informal resources are highly important to them. There are obstacles to accessing such resources, however. First, some residents are completely illiterate and, being unable to read and type, they cannot surf the Internet. They are almost unreachable by any media learning opportunities and rely on state literacy courses. Second, the lack of Internet provision has a negative impact on the learning efforts of many residents. Since neither a computer room nor a free hotspot are available, they are left to their own devices with regard to gaining Internet access. Third, since no official support and guidance to language-learning opportunities on the Internet exist, vernacular knowledge about such opportunities is passed on among networks of site residents and their acquaintances, with more experienced asylum-seekers sharing their resources with newcomers.

In the interviews, our informants presented to us a wide range of digital resources for language learning across various platforms and formats. Remarkably, they seem to rely less on commercially successful software (e.g. Duolingo) than on amateur-produced learning materials (such as video tutorials), language technology (online dictionaries and machine translation, most specifically Google Translate), and self-help online networks.[7]

In the short videos we filmed at the end of the interviews, the two members of the Afghani family, Sarina and Ebrahim, presented to us their favorite German-learning resources. Sarina showed us (aided by her son) a German-learning channel on YouTube, Almani Be Farsi, that specifically caters to speakers of Farsi. Owned by an Afghani teacher who also produces the content, this channel features around 450 videos, all of them produced in the last few years. Mostly targeting beginner levels (A1 and A2), these videos are organized in playlists by grammatical categories, with a few videos on additional topics such as ‘German culture’. The language of instruction is Farsi throughout. The video he demonstrated to us in the interview covers elementary greeting patterns. The first line reads ‘salam = hallo’, and the speaker voice repeats the German greeting a few times to teach its intonation. Interestingly, while Ebrahim searched YouTube for us by typing in the Farsi script, the Farsi-language items on this screen are Latinized (transliterated), and we speculate this is the case in order to appeal to speakers who might be illiterate in Farsi, but are now becoming alphabetized while in Germany.[8]

Ebrahim reported having himself used these videos to learn German back in 2014, when his family arrived in Germany. Having no access to language classes at their first residence site, they were told about this video series by other residents. Ebrahim recalled having watched ‘around forty of these videos’ again and again, writing done the German words and practicing their pronunciation, until he had learned enough words and could speak a little bit himself. In his short video during the interview, Ebrahim first showed us the home-screen of Google Translate, where the list of his ‘frequently used languages’ features Persian, English, German, and Turkish. He critiqued that the machine translations are not always good, then moved on to open another messenger app, Telegram, where he is member of a group chat organized by one of his German-language teachers. He showed us the message stream, full with meme-like images with reference to German, some of them explanations of grammar or vocabulary. He zoomed on one image with German phrases for ‘agree with’ (zustimmen) and pronounced one of them. He then opens another Telegram chat, a machine translation tool by the name of @translategerman_bot, where users can paste in words and have them translated. He demonstrated its usage by typing in a Farsi word, upon which he received a list of German noun and verb equivalents, each with a Farsi translation. He reported being quite competent in handling this tool and demonstrated the opposite direction too, typing in the German word Regierung to receive Farsi equivalents. ‘With these two apps I can learn quite well’, Ebrahim said in conclusion. He then guided us through the various input options for Google Translate, including finger-writing on the screen, producing an audio message, and scanning a written document, and performed the latter skillfully with the interview consent form he signed for us.

7 Discussion and conclusions

In conclusion, the smartphone usage of the refugees we interviewed for this study seems broadly comparable to that of other migrant groups who also draw on a range of software applications to manage their daily routines and maintain transnational family communication. One distinct aspect of refugees is their sole reliance on a smartphone for distant communication and information retrieval. Unlike the earlier study by Witteborn (2015) whose informants spent their online time predominantly in front of a computer, most of the informants in our study do not possess a computer or a laptop and therefore manage their online activities exclusively on a smartphone. Their digital literacy skills with smartphones could be explained by the fact that many adult refugees already possessed a smartphone before being forced to migrate, and that smartphones were already essential on their escape route.

Both interviewed families demonstrate a wide range of digital literacy practices in their daily lives, involving various languages and apps. Older family members in both families use their smartphones to stay in touch with relatives and friends abroad, especially in their home countries, whereas their children’s contacts are mostly located in Germany or the EU. The Syrian and Afghani parents report different education biographies, from a completed middle school to three classes of primary school. This affects their digital practices, leading to specific mode and language choices, as in the case of Omar, whose reading skills are quite poor, resulting in him sticking to spoken Arabic when telephoning or making WhatsApp calls. By contrast, both adolescents attend a regular school in Hamburg and learn German there. Another distinction between the generations in both families is found in their linguistic repertoires. Both adolescents are multilingual with high competence in at least two languages, i.e. their first language and German. Both are eager learners of additional foreign languages. They learn English as a mandatory course in school and on top of that Turkish (Elayla in the foreign language course at school, Ebrahim through daily interaction with Turkish speakers). And while the parents rely on a few well-tried software apps to get by, their children try out a much larger number of apps. In terms of smartphone-based language-learning practices, our explorative study suggests that since the members of this refugee community cannot always rely on the official German courses due to their uncertain legal status, they develop sharing practices, by which software and weblinks are passed on from earlier refugees to newcomers. By sharing online learning sources such as YouTube channels, Facebook pages and language-learning apps, community members create a customized learning portfolio. However, such learning practices rely on stable internet access, the lack of which, according to our informants, is one of the greatest obstacles not only for the acquisition of German, but also for their further social integration.

We conclude with a note on the role smartphones might play in social integration processes. Early large-scale integration studies focused on language acquisition being the main indicator for a successful integration in a host country (Heidelberger Forschungsprojekt 1975; Deppermann et al. 2018). However, our findings suggest that language acquisition among refugees is closely related to their digital practices. Furthermore, smartphone affordances enable their owners to manage the daily routines that are essential upon arrival in a new country: using Google Translate for daily conversations and research, searching useful information about local doctors, looking for jobs and apartments, finding travel routes on Google maps, communicating with schools and teachers, reading and sharing news, documenting important events, and staying in touch with the old and new networks. In our view, three suggestions seem to follow up from the fact that language learning and digital practices are closely linked to one another: first, a prerequisite to successful social integration is not just learning the dominant language, but also being digitally literate and thereby able to manage everyday tasks with digital tools; second, supporting language-learning crucially depends on providing adequate internet access; the precarity of access we found in this residence site is a major drawback in this regard. Third, unlike their legal status suggests, both young and older refugee informants are not bound to one single physical, geographical or communication space. These interact internationally, managing family and friends’ networks all over the globe. Their communication space is characterized by multilingual practices, co-created by interactants active in the virtual and physical spaces. This polycentric environment (Blommaert et al. 2005) has emerged in a natural way, reflecting the life paths of the forced migrants being co-present in multiple communities and being situationally more or less intensively integrated in one or the other community of practice at a time.

References

Androutsopoulos, Jannis/Juffermans, Kasper (eds.) (2014): Digital language practices in superdiversity (= Guest-edited Special issue of Discourse Context & Media 4–5).

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2014): Moments of sharing: Entextualization and linguistic repertoires in social networking. In: Journal of Pragmatics 73, 4–18.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis/Lexander, Kristin V. (submitted): Snakke wolof, skrive fransk - the interplay of mode, language and media choices in transnational family communication.

Barton, David/Lee, Carmen (2013): Language Online. Investigating Digital Texts and Practices. London: Routledge.

Blackledge, Adrian/Creese, Angela (2017): Translanguaging in Mobility. In: Canagarajah, Suresh (ed.): The Routledge Handbook of Migration and Language. London: Routledge, 31–46.

Blommaert, Jan/Collins, James/Slembrouck, Stef (2005): Polycentricity and interactional regimes in ‘global neighborhoods’. In: Ethnography 6 (2), 205–235.

Blommaert, Jan/Backus, Ad (2013): Superdiverse Repertoires and the Individual. In: de Saint-Georges, Ingrid/Weber, Jean-Jacques (eds.): Multilingualism and Multimodality. Current Challenges for Educational Studies. Rotterdam: Sense, 11–32.

Bucher, Taina/Helmond, Anne (2018): The Affordances of Social Media Platforms. In: Burgess, Jean/Poell, Thomas/Marwick, Alice (eds.): The SAGE Handbook of Social Media. London/New York: Sage, 233–253.

Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) (2016): Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2015: Asyl, Migration und Integration. BAMF: 22, URL: https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Broschueren/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2015.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat (BMI) (2016): 890.000 Asylsuchende im Jahr 2015. Pressemitteilung vom 30.09.2016. URL: https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/DE/2016/09/asylsuchende-2015.html.

Busch, Brigitta (2017): Expanding the Notion of the Linguistic Repertoire: On the Concept of Spracherleben - The Lived Experience of Language. In: Applied Linguistics 38 (3), 340–358.

Canagarajah, Suresh (2013): Translingual Practice: Global Englishes and Cosmopolitan Relations. London/New York: Routledge.

Chik, Alice (2018): Learning a language for free: Space and autonomy in adult foreign language learning. In: Murray, Garold/Lamb, Terry (eds.): Space, place and autonomy in language learning. London: Routledge, 44–60.

Demouy, Valérie/Jones, Ann/Kan, Qian/ Kukulska-Hulme, Agnes/ Eardley, Annie (2016): Why and how do distance learners use mobile devices for language learning? In: The EuroCALL Review 24 (1), 10–24.

Deppermann, Arnulf/Cindark, Ibrahim/Hünlich, David/Eichinger, Ludwig (eds.) (2018): Flüchtlinge in Deutschland: Sprachliche und kommunikative Aspekte. Themenheft, Deutsche Sprache 3/2018.

Deumert, Ana (2014): Sociolinguistics and mobile communication. Edinburgh: University Press.

Harney, Nicholas (2013): Precarity, affect and problem solving with mobile phones by asylum seekers, refugees and migrants in Naples, Italy. In: Journal of Refugee Studies 26 (4), 541–557.

Heidelberger Forschungsprojekt (1975): Sprache und Kommunikation ausländischer Arbeiter. Kronberg: Scriptor.

Hutchby, Ian (2001): Conversation and technology: from the telephone to the Internet. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Jacquement, Marco (2017): Sociolinguistic Superdiversity and Asylum. In: Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies 171. URL: https://www.academia.edu/31144096/TPCS_171_Sociolinguistic_superdiversity_and_asylum_by_Marco_Jacquemet.

Jones, Rodney H./Hafner, Christoph A. (2012): Understanding digital literacies: a practical introduction. London: Routledge.

Lai, Chun/Dongping Zheng (2017): Self-directed use of mobile devices for language learning beyond the classroom. In: ReCALL 17, 1–20.

Lexander, Kristin Vold/Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2019): Working with mediagrams: a methodology for collaborative research on mediational repertoires in multilingual families. In: Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Published online, 24 September 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1667363.

Madianou, Mirca (2014): Polymedia communication and mediatized migration: an ethnographic approach. In: Lundby, Knut (ed.): Mediatization of Communication. Berlin: de Gruyter, 323–348.

Madianou, Mirca/Miller, Daniel (2012): Migration and New Media: Transnational Families and Polymedia. London: Routledge.

Madsen, Lian/Karrebæk, Martha/Møller, Janus (eds.) (2016): Everyday languaging: Collaborative research on the language use of children and youth. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.

Nunan, David/Jack C. Richards (2015): Language Learning Beyond the Classroom. London: Routledge.

Scollon, Ron (2001): Mediated discourse: The nexus of practice. London: Routledge.

Sharma, Devyani (2017): Scalar Effects of Social Networks on Language Variation. In: Language Variation and Change 29 (3), 393–418.

Stebbins, Robert A. (1994): The liberal arts hobbies: A neglected subtype of serious leisure. In: Loisir et Société/Society and Leisure 17, 173–186.

Stebbins, Robert A. (2015): The interrelationship of leisure and play: Play as leisure, leisure as play. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Thomas, Minu/Lim, Sun Sun (2010): On maids, mobile phones and social capital—ICT use by female migrant workers in Singapore and its policy implications. In: Katz, James E. (ed.): Mobile Communication and Social Policy. Trenton, NJ: Transaction, 175–190. URL: https://www.academia.edu/12367053/On_maids_mobile_phones_and_social_capital_ICT_use_by_female_migrant_workers_in_Singapore_and_its_policy_implications.

Tubaro, Paola/Casilli, Antonio A./Mounier, Lise (2014): Eliciting Personal Network Data in Web Surveys through Participant-generated Sociograms. In: Field Methods 26 (2), 107–125.

Wall, Melissa/Campbell, Madeline/Janbek, Dana (2015): Syrian refugees and information precarity. In: New media & society 19 (2), 240–254. URL: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1461444815591967.

Wandruszka, Mario (1979): Die Mehrsprachigkeit des Menschen. München: dtv.

Witteborn, Saskia (2015): Becoming (im)perceptible: Forced migrants and virtual practice. In: Journal of refugee studies 28 (3), 350–367.

Appendix

A.1 Transcript conventions

|

• |

minimal pause |

|

(unverst.) |

unclear word/phrase |

|

((2S)) |

measured pause, 2 seconds. |

|

[…] |

omitted word/phrase |

Interviews were transcribed with the EXMARaLDA software.

A.2 Original interview excerpts in German

Excerpt (1): Omar (interpreted by Elayla)

218 E: er schreibt arabisch • aber ganz wenig • so • auch wenn er schreibt macht er Fehler er erkennt die Straße und dadurch auch wenn er nicht • also also er kann die Haltestelle nicht richtig lesen aber wenn er einmal hört und ein Sache in dieser Station guckt dann merkt er • dann bleibt es in seinem Kopf dass es das ist er kann ganz viele Straßen in Deutschland auch wenn ich ein Arzt suche sag ich zu ihm warte • wir suchen das bei Google • er meint zu mir • komm, ich kann das komm hinter mir einfach • so ein Computer im Kopf

Excerpt (2): Kadira (interpreted by Elayla)

178 E: der Unterschied von meinem Vater und meiner Mutter ist immer online • also sie sucht so bestimmte Sachen weil sie lesen besser als • ihn kann • • also sie kann ganz gut deutsch und arabisch lesen aber er zu wenig deswegen kann man im Internet nicht so viel

Excerpt (3): Kadira (interpreted by Elayla)

36 E: sie will sagen, dass sie letzte Woche alleine im Krankenhaus war und dann hat sie das [Google-Übersetzer] benutzt, damit sie mit dem Ärzten sich gut um/verstehen kann.

Excerpt (4): Elayla

340 E: Sie sagt, dass so schlecht is, dass wir kein Internet zuhause haben, dass wir mehr im YouTube was Deutsch, also mehr auf Deutsch lernen oder so. Meine kleineren äh Brüder wollen immer auch so solche Fernsehn auf Deutsch gucken. Also solche Programme für Kinder und so. Aber ich kann das nicht an, also… Einschalten wenn ich kein Internet habe.

Excerpt (5): Elayla

164 E: Eine Freundin. Sie is meine beste Freundin. Und ja, wir schreiben immer • äh auf/ über WhatsApp. Wir sprechen Deutsch. Und äh ich schick ihr • oft so schriftlich. Sie kann Kurdisch und Arabisch. Aber wir reden nur Deutsch. Damit wir nicht unserer Deutsch • also schlechter machen

Excerpt (6): Elayla

17 E: Äh türkische Sprache kann ich n bisschen sprechen, • äh auch ähm gut verstehen, aber schreiben und lesen kann ich nicht. Äh benutzen manchmal. Ich lerne in der Schule Türkisch. • • Wir haben große Kurse in der Schule und wir können auswählen was wir lernen möchten. [...] Ich hab ganz viele Lieder auf Türkisch gelernt und ich singe die immer. Aber als ich in Syrien war, wir haben, ich und meine Schwester immer ähm Serie auf Türkisch gesehen. Aber die haben also auf Arabisch gesprochen. Das ist übersetzt halt.

Excerpt (7): Ebrahim

47 E: Türkisch kann ich bisschen verstehen ja ((2s)) also sprechen bisschen • • ganz kleines bisschen • • das hab ich von meinem Mitschüler gelernt also da wo ich jetzt zur Schule gehe da sind • äh • wir sind 24 Leute • • also äh• ich hab 23 Mitschüler • und • äh • 18 von denen kommen aus der Türkei und deshalb • • die haben mir • so ein bisschen beigebracht

Excerpt (8): Ebrahim

185 E: da wo ich • in der Schule war • erster Tag und Lehrerin • ich war in einer (unverst.)-Klasse • • da wo die Leute • die müssen von Anfang also von ABC • äh ja • aber da konnte ich schon Deutsch • und Lehrerin war • äh also war ein bisschen enttäuscht • Sie hat mich gefragt • Wie kannst du so gut Deutsch? • Ich war damals so • zwei Monate in Deutschland da hab ich gesagt • so hab ich • also selber Deutsch gelernt • ohne • konnte das ohne Grammatik

Excerpt (9): Ebrahim

117 E: Anrufe • weil ich • ich arbeite • also ich mach Nebenjob • arbeite in Hotel • und mein Chef ruft ruft mich manchmal an • und ich muss da anrufen und ich mach viele Termine für meine Mutter • also vom Arzt oder • wir bekommen immer Wohnungsangebote von Baugenossenschaft • da muss ich immer anrufen • und sagen dass ich zur • dass • dass wir immer eine • so Zusage sagen also muss man persönlich anrufen