Vol 2 (2019), No 2: 123–156

DOI: 10.21248/jfml.2019.20

Face-Work and Identity Construction Online

Abstract

In this article, we build on research arguing that linguistic self-representation on social media can be viewed as a form of face-work and that the strategies employed by users are influenced by both a desire to connect with others and a need to preserve privacy. Drawing on our own analyses of usernames as well as that of others which were conducted as part of a large-scale project investigating usernames in 14 languages (Schlobinski/T. Siever 2018a), we argue that these conflicting goals of wanting to be recognised as an authentic member of an in-group while retaining a degree of anonymity are also observable in the choice of username. Online self-naming can thus be viewed as a key practice in the debate of face-work on social media platforms, because names and naming strategies can be studied more readily than broader and more complex aspects, such as stylistic variation or text-image interdependence, while at the same time forming part of these.

Keywords: usernames, self-naming, handles, face-work, social media, onomastics

1 Introduction: Creating a Self-Image online[1]

When discussing self-representation in online spaces in public discourse, the predominant focus is often on the detrimental effects of a distorted reality that is created by presenting only a polished, positive version of oneself only (Turkle 2012), a concept that is also well-established in academic discourse (but in a more nuanced way), in particular that “[users] can freely decide to a large extent how they want to present themselves to their communication partners” (Bedijs/Held/Maaß 2014: 10). From a linguistic point of view, however, there is a lack of systematic investigation and comprehensive analytic and theoretical framework for identity construction online. In this article, we discuss studies that have addressed the topic either explicitly or implicitly and aim to demonstrate that identity construction is skillfully and consciously employed by people engaging in online communication.

When investigating identity construction online, it is not only important to consider “Who says what in which channel to whom with which effect?” (Lasswell 1948) but also “with which code?” (Androutsopoulos 2003: 1), code being the linguistic layer of a mediated message. We address these questions and investigate in what way and to what extent social, technical, platform-specific and pragmatic affordances shape online identity construction by analysing the stylistic variation of different user communities, thus leading to a comprehensive study of the strategies involved: how users stylistically align with an online community, for example Twitter, using self-naming strategies.

Identity construction online can be viewed as a form of face-work in Goffmanian sense (Fröhlich 2014) and manifests in a wide-ranging set of practices, e. g. the choice of username (also referred to as screennames or nicknames (cf. Aleksiejuk 2016b) but for clarity, only username will be used to refer to this type of name throughout this article), form and content of online profiles and status messages, which contribute to the linguistic positioning of users. The alignment that “speakers and hearers take toward each other and toward the content of their talk” (Goffman 1981: 128) is ever-shifting and is linguistically signalled by the interlocutors (see also Graham 2015).

According to Bedijs/Held/Maaß (2014) as well as our own work on internet onomastics (Kersten/Lotze 2018; Lotze/Kersten 2020; Lotze/Kersten under review), the face-work strategies employed by users on social media are influenced by a desire to connect with other users and an increasing need to preserve privacy and, at least up to a point, anonymity. These conflicting goals of wanting to be recognised as an authentic member of an in-group while retaining a degree of anonymity are, for example, observable in the choice of username (i. e. incorporation of elements of the onymic inventory of a given language, the level of opacity with which this is done and the use of common nouns or other parts of speech communicating specific interests or group memberships to signal group membership but then potentially foregoing authenticity; for more detail, see discussion in section 3.2.2). Therefore, usernames are a key factor to consider and analyse in the light of the dilemmas faced when doing face-work online:

• the social positioning between private and public discourse (Bedijs/Held/Maaß 2014);

• the collapse of contexts online (boyd/Marwick 2011), i. e. the possibility for de- and re-contextualisation of online postings, resulting in the fact that “the exact composition of the audience for any one post is therefore unknowable” (Seargeant/Tagg 2014: 8);

• the transformation of all traditional forms of audience design into a new form of face-work online, which is sensitive to the problems of ‘privacy vs. authenticity’ and ‘context collapse’.

In this article we discuss self-naming[2] as a conscious choice of a username (or usernames) and a form of face-work. We understand online self-naming as a key practice in the debate on face-work on social media platforms, because names and naming strategies can be studied more readily than broader and more complex aspects, such as stylistic variation or text-image interdependence, while at the same time forming part of these.

The aim of this article is to discuss how username onomastics can contribute to the study of usernames as a means of self-expression and self-authentication drawing on research on community-specific online styles (i. e. variational linguistic perspective). Throughout, we refer back to our study on English usernames that was part of a large-scale project on username choice across 14 languages conducted by us and colleagues under the helm of Schlobinski/T. Siever (2018a). The empirical data of our study as well as those of our colleagues who worked on the project Nicknamen international have been published in an edited volume (Schlobinski/T. Siever 2018a), however the discussion there focusses predominantly on structural and functional aspects of usernames (i. e. structural and functional perspective). A more detailed discussion of the onomastics of self-naming and identity construction can be found in Lotze/Kersten (2020) where doing identity is discussed in detail and which includes definitions of terms in relation to self-naming and identity construction, drawing on philosophical, sociological and psychological approaches of identity and self (i. e. onomastic and philosophical). An additional contribution focussing on the methodological aspects and challenges of online onomastics is currently under review (Lotze/ Kersten under review) (i. e. the methodological perspective). Since the present paper is intended to be an extension of our analyses in Schlobinski/T. Siever (2018) and draws on the results of our original study of English usernames for illustrative purposes only, it does not follow the traditional Introduction, Methodology, Results, Analysis, Discussion structure, but is instead content- and theory-driven.

1.1 Authenticity, Transparency and Narcissism in the Digital Age

The ‘digital revolution’ – which has been described as the fourth major media revolution (Schlobinski 2012: 18) – has not only freed global and mobile communication from most of its physical constraints, it has also given permanence to what had hitherto been mostly ephemeral communication. The increased reach of any form of communication and seemingly limitless storage capacity have resulted in entirely new interactional contexts. It has also put the users’ privacy at risk in two ways: first, from a (semi-)public audience who can read what may once have been considered to be private communication and, second, from large-scale data storage and analysis by Silicon Valley companies.

This blurring of private and public spheres poses a dilemma for the users: their wish to engage in social interaction on the one hand and their desire to protect one’s privacy on the other. The result is a new type of face-work (Goffman 1967): How do you communicate when you know that a considerable number of people may be reading along?

This question is currently the focus of public debate and is framed either in terms of a compulsion to be authentic in an “Age of Transparency” (Sifry 2011), excessive self-presentation in an “Age of Narcissism” (Durvasula 2016) or as the symptom of a “Narcissism Epidemic” (Twenge/Campbell 2009). Are these new forms of interaction really the driving factor behind the predicament described above or are they actually just all-too familiar human behaviour, albeit in slightly snazzier clothing? In other words, is this new and potentially narcissistic form of face-work really a phenomenon that can be attributed to the rise in social media use?

Without wanting to succumb entirely to cultural pessimism, it is important to remember that, from a media studies perspective, social media use can be both a filter and a driver for new ideas and trends. Friend-based social networks and hashtag communities can result in echo chambers and filter bubbles (Hegelich/Shahrezaye 2015) leading to an acceleration of stylistic variation and differentiation. Individuals can become well known to millions almost overnight and thus gain a tremendous amount of influence, an aspect of which is for example the choice of username, as can be exemplified by the YouTuber LeFloid who interviewed the German chancellor Angela Merkel on his channel in 2015, Dagi Bee, Germany’s most popular beauty YouTube star, as well as Zoella, her counterpart in the UK who, among other things, launched her own range of products. When traditional media write about so-called social media stars, their ‘real’, i. e. their birth and/or legal, names are occasionally mentioned, but it is the username that is inextricably linked to the ‘brand’ and that followers and fans recognize. The name thus becomes the brand and is celebrated by the followers, e. g. the fans of cosmetics influencer Dagi Bee allude to her name by including the bee emoji in their comments and thus signaling their status as her followers.

The possibility of internet stardom in turn seems to appeal to certain individuals more than others. A recent comprehensive psychological study by the Hans Bredow Institute using standard narcissism questionnaires (Hölig 2018) found that Twitter users who tweet both frequently and regularly exhibit pronounced narcissistic traits. Hölig (2018) found that 10 % of Twitter subscribers produce 90 % of the content and that these particularly active users also score high on the standardised narcissism scale. This begs the question whether the differences between heavy users (i. e. the minority who produces the majority of the content) and the less vocal majority (i. e. those who are predominantly consumers rather than content creators) also manifests in linguistic features (e. g. their choice of username, the focus of this article).

Researchers have proposed various criteria for interpreting users’ styles. Boyd/Marwick (2011), for example, investigated teenagers’ online privacy practices and established what could be termed exclusivity through the use of “in-jokes” and group-specific lexis, and positivity by avoiding sad or controversial topics, thus creating a polished, retouched, curated image of themselves (see also Turkle 2012).

Other studies found that users create subjectivity and emotionality through conventionalised emoji usage and formulaic group-specific phraseology, often hyperbolic in nature (e. g. allerallerbeste Freundin ‘absolute best friend ever’ or ich verlass dich nie ‘I’ll never leave you’). In a case study of a group of adolescent girls on the now defunct German social media platform SchülerVZ, Voigt (2015a) describes how this group presents themselves as particularly cute and popular by using a specific style (emoticons, iteration of letters, relationship phrases and intensifiers) and deduces from this rather too generally that “Schulmädchen”, i. e. school girls [sic], use a new variety of communication online (Voigt 2015b). We would argue that it is impossible to make any such general claims based on a single case study and that what is described is, from a sociolinguistic perspective, if anything, a style rather than a variety. The studies nevertheless highlight that there is a need for further, more comprehensive and generalizable studies of face-work online which, instead of perpetuating stereotypes, need to be methodologically sound and sufficiently detailed and broad in equal measure.

To this end, self-naming can be investigated regarding the extent with which users conform to a Community of Practice (CoP, Lave/ Wenger 1991) and the implicit norms associated with this CoP or, alternatively, how they try to distance themselves from it. As part of a contrastive study (Schlobinski/T. Siever 2018a; for a more detailed discussion see below) of usernames, we compared usernames and self-naming strategies, and found functional similarities and that the structural means to establish a sociolinguistic function differ (Kersten/Lotze 2018), for example in terms of the degree of privacy retained by anonymising usernames or by alignment with a particular group through judicious username choice.

1.2 Online Styles

This section outlines the current discourse on narcissistic self-presentation online and the state of the art in style analysis, face-work and identity.

Both German and English language digitally mediated interaction (DMI) can look back on more than 20 years of academic debate of the linguistic behaviour of users. Despite this, it is still not fully understood which platform-related and socio-pragmatic variables influence the communicative behaviour of users and their engagement in online communities. This may partly be due to the fact that theory generation takes time and is often outpaced by technological change. For the younger generation, a life without social media is inconceivable; even though social media have only become a part of our lives very recently. It is all the more important to work on a more accurate definition of these new social spheres and their communicative agents (to borrow Habermas’ [1993] terminology).

Following a phase that mainly focused on describing the early internet and its affordances by comparing it to other forms of written communication (English: e. g. Herring 1996; German: e. g. Runkehl/ Schlobinski/Siever 1998), researchers began investigating whether the internet gave rise to a new register, so-called “Netspeak” (Crystal 2001, 2010). The idea of a homogenous online register or style was quickly refuted in light of the diversity of communicative contexts and the heterogeneity of the user groups themselves. Today, the linguistic and multimodal stylistic variants that are present in DMI are viewed as community-specific and as diverse as these communities and their participants.

Nevertheless, DMI can result in the emergence and conventionalisation of certain features, such as the use of emoticons/emojis and morphological or syntactic abbreviations, which in turn are often seen as typical for DMI (see e. g. Baron 2008; Beißwenger 2007; Szurawitzki 2010). The conceptional orality of, in particular synchronous written, communication has taken on a prominent role in this context (see e. g. Dürscheid 2007 with reference to Koch/ Oesterreicher 1985). Texting or text-speak as a form of DMI is no longer regarded as merely a result of the affordances and restrictions im-posed by the medium; instead it is regarded as a reflection of the user’s underlying cognitive processes (see e. g. Dürscheid 2016 for an in-depth discussion). The focus of inquiry consequently shifts to the user’s experience of online communication in real time and therefore the language of immediacy (as opposed to distance). As a result, studies of DMI tend to not to focus on the medium alone anymore but also on the cognitive dimension of the user experience.

The problem with this approach is that communication in the digital age has been defined with recourse to traditional concepts of orality and literacy, which fail to adequately capture this new form of literacy (cf. Androutsopoulos 2007), in particular its multimodality. Consequently, few definitions of linguistic practices used in the vast variety of online contexts, communities and networks are widely accepted.

We argue that any investigation in this field has to be able to adequately capture the fundamental sociological and psychological principles of human interaction and identity construction (Erikson 1974; Keupp et al. 2002), self-presentation (i. e. face-work, Goffman 1967) and group behaviour within a CoP. Taking into account the basic principles of human interaction and social community is in our view instrumental in uncovering variables that have hitherto not been widely studied and to identify which communicative strategies are simply “old wine in new wineskins” (Dürscheid 2007) and which ones are pivotal and genuinely novel (see also Herring/Stein/Virtanen 2013).

The first step towards doing this is to conduct further analyses of identity construction online by investigating the degree to which online identities are constructed by ‘writing oneself into being’ (as exemplified in the choice of usernames) and the effect which this newly crafted existence has on all subsequent communication.

The second compounding factor is the loss of clear boundaries between the private and the public (Bedijs/Held/Maaß 2014). Everyone who engages with others online is confronted with the desire for social connection which in turn necessitates at least a degree of authenticity and identifiability on the one hand and the conflicting desire to protect one’s privacy by disclosing as little as possible on the other, but how these are addressed varies from communicative situation to communicative situation as well the CoP.

As a result, there is a broad spectrum of self-naming strategies ranging from usernames that are utterly opaque to those containing common nouns or other parts of speech and/or (parts of) the onymic inventory of the given language as well as everything in between (Kersten/Lotze 2018; Lotze/Kersten 2020). This is just one of numerous examples of the stylistic variation in communicative strategies which have evolved alongside the phenomenon of private communication in a public space.

The third factor is the communities the individual does or wants to belong to. Many aspects of face-work and group effects (e. g. filter bubbles and echo chambers) can be linked to the positioning of oneself in relation to other groups. Research has found evidence of adaptation processes in the form of interactive alignment in online communities at both the lexical and syntactic level (for face-to-face dialogues see Pickering/Garrod 2004, for DMI see Lotze 2016). In the case study discussed above, Voigt (2015b) discusses stylistic accommodation among adolescents by shared use of relationship phrases or via emulated prosody (Haase et al. 1997), which is often represented by the iteration of letters (T. Siever 2006) and emoticon usage. On a functional level, boyd/Marwick (2011) observed a tendency among adolescents to engage in linguistic positivity and emotionality as a reaction to the possibility of any communication on social media potentially being read by others who are not the intended audience. There is also evidence of adaptation strategies in choosing usernames within different Communities of Practice (e. g. Twitter and Flickr: Kersten/Lotze 2018; Facebook and online gaming: Kaziaba 2016; more generally: Aleksiejuk 2017). Alignment with an “in-group” (Tajfel/Turner 1986) can be found at all levels of interaction. With regard to political linguistics/discourse analysis (Twitter: Hegelich/Shahrezaye 2015) and research on linguistic cyberbullying (Marx 2017), there is evidence that valorisation of the in-group can go hand-in-hand with a devalorisation of an out-group in the form of othering and scapegoating (see also Pörksen 2005).

The guiding questions are thus the following: how do people ‘do naming’ when choosing a username to participate in online communication; to what extent is this platform-dependent or motivated by a desire to align with a particular group of users; which strategies are employed to preserve privacy and how do users cope with the conflicting desire to preserve privacy (and therefore anonymity) on the one hand and disclose enough information about themselves to be recognisable (and therefore make themselves partially or fully identifiable) on the other hand?

In the following, we provide an overview of the theoretical concepts of onomastics and digitally-mediated interaction research that are relevant for the discussion at hand, focussing in particular on face-work, and relate these to our findings of an analysis of 500 English usernames (Kersten/Lotze 2018) as well as more generally the findings of the a project analysing usernames across the 14 languages our data analysis formed part of (Schlobinski/Siever 2018a).

2 Naming and Identity Construction

The topics of naming, face-work and stance are closely related to the philosophical topic of the identity of the individual, which in turn is linked to the very essence of human existence. Therefore, the academic discourse on human identity goes back to the beginnings of philosophy and shares links with several other disciplines, such as the psychology of the individual (as well as developmental psychology), social psychology, sociology and linguistics. The following section outlines the theoretical frameworks of identity construction in Western philosophy, sociology and linguistics as well as the relevance of every aspect of these theoretical approaches for onomastics.

In Western philosophy, the individual is defined as the very entity which cannot be divided, as discussed in Plato’s Cratylus dialogue with reference to the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus. The individual is in union with herself (Latin: idem = ‘the same’), i. e. in spite of dynamic development, the individual must recognize herself everyday as one indivisible entity (both qualitatively and numerically). This indivisible being is referred to by a name which is (at least ideally) mono-referential, i. e. has one unique referent (cf. Nübling/ Fahlbusch/Heuser 2015; Hansack 2004). The being is able to reflect on their inner identity via their consciousness, which is what John Locke calls the ‘self’ (Locke, Essay: II, 27, 8). It is this capacity of critical self-reflection that makes the individual a rational agent in the Kantian sense, who is ethically responsible for their actions (Kant, MdS VI 223). This in turn can be related back to onomastics, because an official or legal name typically refers to an authentic person with rights and duties (see e. g. Lettmaier 2015 on the legal aspects of names in the UK; Lawson 2016; Nübling/Fahlbusch/ Heuser 2015).

In more recent times, the constructivist school shifted the focus from the individual’s inner conscious experience of identity to the inter-personal construction of identity. While a radical form of constructivism could be criticized as being relativistic, the idea of identity as a process rather than a product has proven to be fruitful in a wide range of disciplines. Following this line of reasoning, identity is subject to interactional negotiation and is therefore a social construct, which in turn is symbolically transmitted (Mead 1978).

In post-modern approaches identity is seen as a ‘patchwork’ of partial identities that are relevant for different aspects of one’s life (e. g. me as an academic, me as a singer). Identity is conveyed in a number of ways, linguistic and otherwise, and it is only the choices made that we can tap into when trying to analyse how linguistic resources, in this instance usernames, are used to construct identity.

In onomastics, this is then linked to the idea that a person can have more than one name (e. g. a family name, one or more given names, pet names, pseudonyms, usernames etc.; see Hansack 2004; see also Antos 2004 and Nicolaisen 1999 on how names are subject to change over time and dependent on the situation).

As discussed above, the concept of social identity construction is closely related to Goffman’s (1967) notion of face-work, because we do not necessarily show each other our true, authentic, inner-most selves, but rather a more polished version, a mask for social interaction, which Goffman refers to as the social “face”. Using empirical methods, we can only ever really tap into a speaker’s face-work, not their identity and we argue that self-naming practices online are a form of such face-work.

Face as a person’s social value can also be negotiated linguistically. This negotiation process can be interpreted with Bucholtz and Hall’s (2005) “principle of emergence” as “doing identity”. In onomastics, online naming is also seen as a negotiated process (“doing naming”, see Aldrin 2011).

Following Bucholtz/Hall (2005), this can be viewed as the positioning of the individual in relation to an online community, which in turn is a CoP. The username can indicate whether the individual is part of an in-group (Tajfel/Turner 1986) with regards to a specific topic, a fandom etc., while at the same time excluding outsiders by referencing a topic, a fandom etc., which only the initiated would be able to recognize (“principle of positionality”, “principle of indexicality”, Bucholtz/Hall 2005).

Consequently, in our analysis of online identity construction we adopt the post-modern view of identity as a patchwork of partial identities which are negotiated in relation to a CoP and the basic principles of linguistic construction of identity as defined by Bucholtz and Hall (2005) as “emergence”, “positionality”, “indexicality”, “relationality” and “partialness”:

• Emergence: Identity is understood to be the result of an interactive negotiation process and can thus be interpreted in the context of an interacting doing approach (doing gender, doing identity).

• Positionality: Identity is constituted as a function of spatial and temporal variables as studied by traditional ethnography (diatopic and diachronic variation).

• Indexicality: The process of identity construction is indexical, which means that identity is constituted in relation to social groups to which one refers with certain culturally grown linguistic means (labels, style characteristics).

• Relationality: Identity is replaced by concrete semantic relations such as similarity, difference, naturalness vs. artificiality or power vs. impotence constituted, e. g. through by self-staging as authoritative.

• Partialness: Because identity is intersubjectively constituted, it is always only partially experienceable, interpretable, etc. and therefore agentivity is fundamentally collaborative.

Name choice can also be interpreted as a partial aspect of the identity constitution of an individual. As a sociolinguistically relevant practice, name choice could be understood to be an interactive negotiation process (doing naming, see also Aldrin 2011). Furthermore, name choice often includes a temporal or spatial positioning relative to a group (fashionable names, regional names). Names refer indexically to social groups (see Nübling 2017: Charlotte vs. Chantal). Self-naming practices can even be interpreted semantically in relation to certain relevant topoi (e. g. self-representation as authentic by using one’s real name on social media); name choice is thus a genuinely collaborative, only partially controllable process that involves choices between names that have been bestowed on ones (birth or legal names, nicknames) and self-naming (usernames, pseudonyms[3]).

To break down the concepts mentioned above and to systematise the explanation of empirical data on self-naming online we posit four main principles of onomastic identity construction as a useful framework of interpretation. These are:

• the use of names to establish mono-referentiality to a unique referent (Nübling/Fahlbusch/Heuser 2015)

• names as a means to model the human consciousness (following Locke, Essay: II, 27, 8)

• names as a device to authenticate oneself as a rational agent with a concept of ethical responsibility (following Kant, MdS VI 223))

• the use of names to position the individual in relation to social groups (Bucholtz/Hall 2005)

In the following section, we discuss our own research findings on online self-naming as well as those of others. This is mainly done in the light of these main principles of onomastic identity construction following the broader concepts of online face-work with its restrictions and affordances (see Bedijs/Held/Maaß 2014, Tagg 2015) and identity construction as “doing identity” following Bucholtz and Hall (2005) in relation to Communities of Practice (Lave/Wenger 1991).

3 Self-Naming Online as Face-Work

3.1 New Parameters for Face-Work Online

It can be argued that people have always striven to put the best foot forward and to present themselves in the most positive light possible. Radford et al. (2011: 447), for example, discuss the way in which users “actively create and maintain face” in Live Chat Reference Interactions, even though it is a very goal-directed form of interaction. They also note that, although some have argued that DMI is inherently levelling and democratic, since all clues about ethnicity, gender etc. are supposedly absent, this is not actually the case since cues are derived from e. g. email addresses and other types of username (Radford et al. 2011; see also Barton/Lee 2014, chapter 6).

As discussed above, the digital revolution has led to a blurring of the boundaries between private and public spheres, which in turn leads to the conundrum the users of social media find themselves in, namely that between authenticity and anonymity. These are conflicting goals, in particular the desire to remain anonymous and the fact that users cannot be sure who is reading their contributions, which make it difficult to identify the audiences (Graham 2015) on the one hand, and the need to provide important identity cues to the co-participants on the other. Graham (2015) also notes that as interlocutors grow more comfortable with each other they may disclose more about themselves, thus reducing their anonymity and privacy. She also argues that the degree of control as to who the audience is is intricately linked to how users choose to present themselves. One strategy to potentially retain a level of control is to compromise in terms of self-naming by combining parts of one’s ‘real’ name with other group- or platform-specific lexis, since a username, “as the first interaction a person has with a platform, sets the tone for how communication and content flows through platforms” (Van der Nagel 2018: 312).

While it has been argued that the online sphere could be described as the stage in the Goffmanian sense and the offline life as backstage (see e. g. Bullingham/Vasconcelos 2013), this differentiation may not be feasible in the light of blurred boundaries between online and offline communication. Gatson (2011), for example, observed in her study of the Buffy the Vampire Slayer fan community that offline relationships between people posting on the fan site were reflected in their usernames. On the other hand, the strategies described above may alone not be enough to be perceived to be an authentic person: Angouri (2015) discusses an example in which one of the participants in a forum dispute makes a clear distinction between a ‘username’ and a ‘real’ person, stating that “besides I am addressing a username [nickname in the Greek original] not someone I personally know, we are kept apart by the interface! :)” (Angouri 2015: 333). The user in question may potentially feel this way because the other user did not disclose enough information about themselves through their username.

In the context of data protection during ethnographic studies, Varis (2015) goes so far as to argue that usernames and avatars should not be regarded as not being legal names, since they are being used to present oneself online and should therefore be protected just like any other kind of personal data. Furthermore, Varis (2015) posits that the distinction between ‘false’ profiles and ‘real’ selves is rooted in the notion that the internet is somehow less ‘real’ that the offline world. Users often perceive others they communicate with online as friends and, as discussed above, the lines between on- and offline worlds become increasingly blurred. There is evidence of careful management of usernames (e. g. Thomas 2007; Gatson 2011; Hagström 2012), the days in which usernames were regarded to be mostly ad hoc creations without much meaning are long gone (Bechar-Israeli 1995; Kaziaba 2013).

Many users use the same or similar usernames across different platforms and contexts (Varis 2015), leading to conscious use of the affordances and constraints of the platforms used, meaning that “people are better able to strategically self-present through the platforms they choose” (Van der Nagel 2017: 314) and make informed choices on how much they disclose when, where and to which perceived audience, which Van der Nagel (2017: 326) likens to “what in a professional arena would be an audience segmentation strategy”, which could be interpreted to be a strategy to counteract context collapse. The important point here is that the technical affordances are “possibilities of action” (van der Nagel 2017: 314), even if some encourage the use of ‘real’ names, which users are also known to circumvent, for example in the data from the study discussed in more detail below (Kersten/Lotze 2018), people filled in the box requiring them to disclose their location with anywhere or Not telling. Users therefore seem to strive for at least a modicum of control over context collapse and one way in which they address this is in the choice of username.

A study of usernames in an online dating context (Bullingham/ Vasconcelos 2013: 18) found that usernames “can, in Goffman’s terms, act as a personal front” creating a reaction in other users, for example when asked to rate the attractiveness of users based on their usernames. Similarly, if a username exhibits a trait that is not desirable in a particular communicative context (e. g. a username suggestive of masculinity in a chatroom frequented by and meant for lesbians), the users may face rejection (Del-Teso-Craviotto 2008).

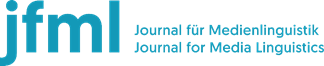

Figure 1: Notions of identity, self and face in DMI (Fröhlich 2014: 117).

As outlined above, we differentiate between the identity of a person as a unit in a patchwork of partial identities, the self as a self-reflexive component in the form of a self-aware being, and the social face which is presented in interaction (cf. Fröhlich 2014).

3.2 Empirical Studies: The International Username Project[4]

To illustrate our argument that username choice does indeed constitute a form of face-work and that names are negotiated, we will refer to results of our empirical study on usernames which combined a quantitative corpus study on the lexis, syntax and morphology of online names with a qualitative questionnaire on the motivation of name choices. As part of this study, we adopted an onomastic approach by investigating whether users tend to give their actual, i. e. ‘real’, names on a platform or rather opt for other naming strategies, such as appellatives, short forms of their names or childhood nicknames or a combination of these.

3.2.1 Quantitative Analysis of Usernames

Research design: For the corpus study on the structure of usernames, the authors worked on Anglophone online self-naming practices and collected 500 usernames from predominantly British platforms. This was done as part of a larger project analysing self-naming practices across 14 different languages and cultures (Schlobinski/T. Siever 2018a), among which are German, Italian, Swedish, Japanese and Chinese, which in turn provided a general framework for data collection and analysis to ensure overall comparability that all project members used no matter which language they focused on.[5]

For all 14 languages, a comparable dataset of 500 usernames was analysed which comprised the following: 100 names from Twitter, Flickr, a TV forum (or comments on a TV show if possible), a newspaper forum and an IT forum. To facilitate comparability, the different language datasets followed the same data collection procedure. If certain platforms were unavailable in specific countries, another service with similar functionality and popularity was chosen in its stead (e. g. Chinese: Weibo instead of Twitter; for a detailed discussion of slight deviations from this general data collection procedure, see sections X.3 Empirische Basis of the individual chapters in Schlobinski/Siever 2018a).

The names collected were analysed using a predefined tag set, including, but not limited to morphology and syntax, conceptual orality and orthographic features. A lexical and semantic classification was also carried out.

All project teams shared this tag set for those categories that were comparable across languages (onomastic categories, lexical-semantic categories). During tagging, language-specific or other additional criteria could be added. This shared tag set approach was used because software for automatic analyses and contrastive comparison was developed specifically for the project to ensure a level of comparability across languages.[6]

In order to generate a balanced sample that included different user types, the British usernames were collected from a variety of different social media sites (Twitter, Flickr, two types of below-the-line comments, one on current TV programmes in a broadsheet, the other on political articles in the yellow press, and forum threads from a tech forum; 100 names from each) to gain insights into self-naming strategies used in a predominantly UK context (for a detailed discussion of how this was achieved, see Kersten/Lotze 2018).

Results:[7] 57.4 % of all British usernames in the corpus are what was classed as transparent pseudonyms following the project-wide definition that they do not contain any ‘real’ name(s) (mooncarrot) at all or, if they do contain elements that look like ‘real’ names, these clearly are not the user’s legal or birth name (Gregor Samsa) or contain other elements in addition to the anthroponym(s). The resulting group of usernames often contains company, product or group names in addition to anthroponyms (pattern: FN LN Photography on Flickr) or consist of language play based on anthroponyms (mariolensa, a combination of the name the singer and 1940/50s film star Mario Lanza and the appellative lens). The proportion of pseudonyms was highest in the Twitter subcorpus at 66 % and lowest in the PC forum at 45 %. A possible explanation might be that users in the PC forum strife to present themselves as trustworthy experts and authentication is particularly important for this type of interaction.

The other names were full or short versions of personal names. 55 % of all names are compounds following Nübling, Fahlbusch and Heuser’s (2015) categorisation of the combination of first name and last name as compounding. For example, Saskia Kersten would be analysed as a compound (on the morphologic level) not as a noun phrase in form of an apposition (syntactic level). 11.6 % contain word play (e. g. mimicking anthroponyms: BillyGoat75, A Breeze or exploiting homophony: eye pad, SereniTEA). 73 % of all usernames exhibit unconventional orthography (omission of spaces/use of delimiter [@Favstar_Bot] or a deliberate use of capitals [CrazyWitchLady], which can be readily explained by the technical constraints of the platforms that e. g. do not allow spaces to be incorporated in user-names, forcing the users to resort to other strategies of indicating word boundaries instead. 33 % of all usernames make use of grapho-stylistics, i. e. numbers or other strategies often regarded to be ‘typical’ of DMI (> 1 %, Fruit Bat /\0/\).

Morphologically, 88 % of all usernames were based on nouns, either with an onymic or an appellative base, as well as on creative combinations of the two (a ** squirrel, j ****** daylight). Other parts of speech were present, but far less frequent, e. g. verbs (4 %, e. g. changed), interjections, onomatopoeia and pronouns (the remaining 5 %, e. g. YeahYeahYeah, Spluuuuurgh, usasoneiaswe) as well as non-analysable forms (e. g. mwbwey123) (for a more detailed analysis, see Kersten/Lotze 2018).

Of the 500 usernames in the corpus, 226 could be analysed as syntagmas, most of them as appositions[8] (24 %, consisting of names + numbers [@D **** EW ***** 17] or names + title [Lady of Nothing]), imperatives (@grabthisbook) or ad hoc constructions for the intro-duction of postings (e. g. Just me thinking). All in all, usernames that constitute a clause with a finite verb are extremely rare (5 %).

3.2.2 Qualitative Analysis of Self-Naming Practices

In spring/summer 2017, qualitative data on self-naming practices were collected using a questionnaire[9], in order to better understand the motives behind choosing a nickname and to tap into username choice in the light of different communities of practice. 71 participants were asked about their self-naming practices and the motivation behind their choice of username, the nature of which informants could disclose as vaguely or specifically as they wished to retain their privacy. Informants could also ask for their actual user-names not to be included in any publications; the examples below are therefore ones that informants gave permission to be used. Most of them were students based in the UK (78.9 % female, 21.1 % male) with an age between 19 and 23 years.

As part of this study, 121 usernames with explanations of how and why these were chosen were collected in total in an open questionnaire design, which was part of the international nickname project. The students were able to fill in more than one name, if they used different ones on different platforms.

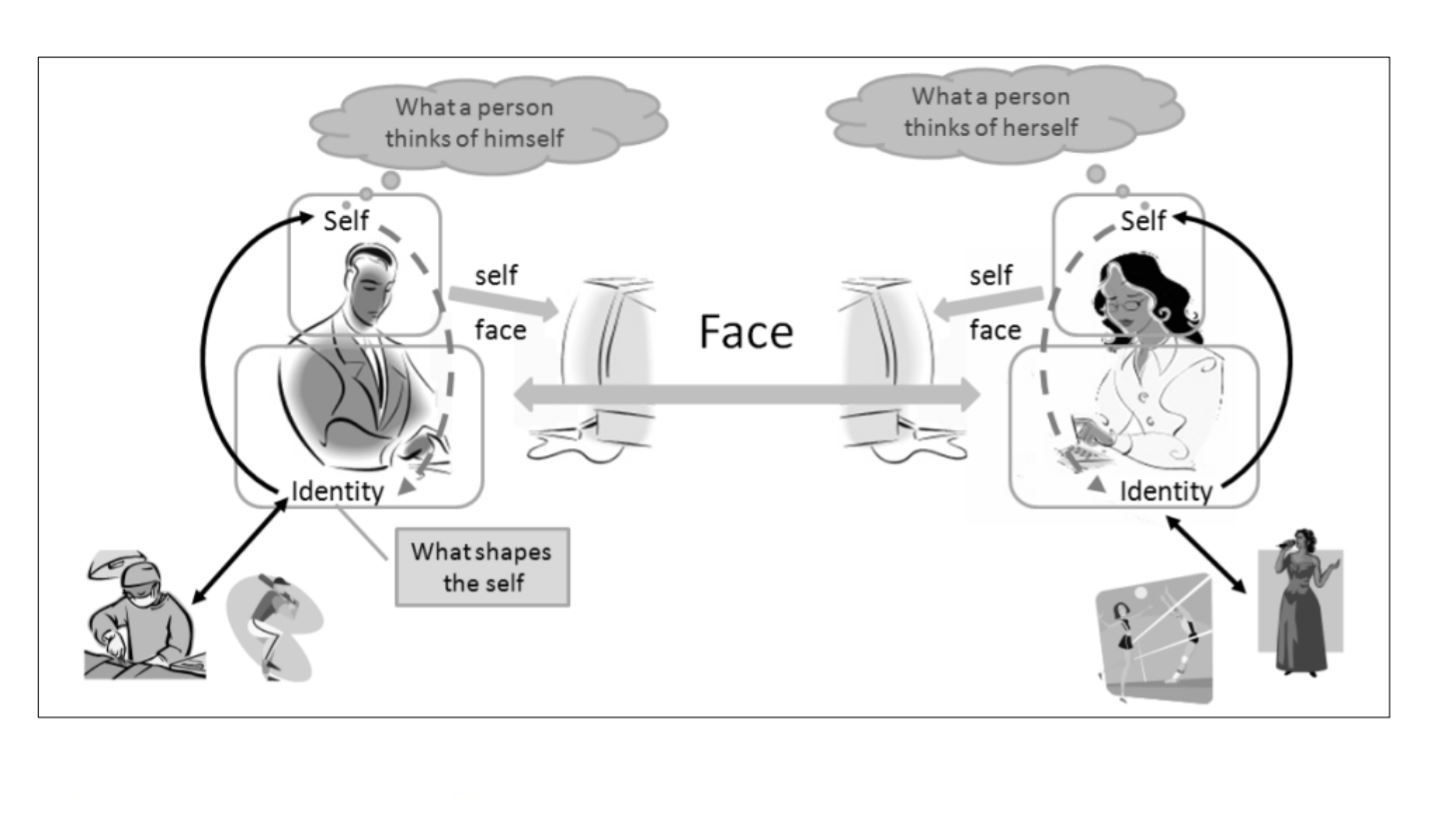

We clustered the usernames together with their motivations of name choice along three continua: a) Authenticity and Anonymity, b) Individualisation and Group Convergence, and c) Phonic and Graphic Aesthetics. The interpretation of self-naming practices on these continua was driven by the insight that users see the decision between personal authenticity or anonymity on the web not as a dichotomous choice between incorporating their full name or a completely opaque username but rather came up with interesting compromises.

The continuum in this model is solely based on the cognitive level of name choice. Users do not decide between two categories, but choose from a range of different variants between two poles. We understand the choices themselves as fluid. At the morphological and syntactic level of the names chosen, these choices manifest in concrete word forms or constructions that may contain more or fewer elements of the sematic domains of the two decision poles (full name, nickname from childhood, nickname from childhood + real age, real first name + appellative addend, etc.). User choices can be very creative, therefore we view them as a continuum, not a scale with discrete increments.

Authenticity-Anonymity Continuum: 59 % of usernames appear to be (at least in part) part of the onymic inventory. 27 % of usernames do not contain any element of standard onymic inventtory (giraffesocks) with a typical explanation being “don’t give my full name on a large platform”. The affordances of the platforms for which the username is created seem to lead to different strategies of name choice, since the users face the authenticity/privacy dilemma and context collapse. 14 % of usernames can be interpreted to reflect strategies of compromise, because they contain initials, middle names or childhood nicknames that are only transparent to an in-group.

Individualisation-Group Convergence Continuum: Most of the participants mentioned some form of identity work in relation to the online community in question (see Seargeant/Tagg 2014). DARK_eXtreme chose this name for a gaming platform “to indicate I was part of a group”. And PrincessMonoko wants to show that they are part of a anime fandom and thus attract other fans because “we share similar info and content”. Consequently, in this case the name itself is seen as aiding in creating a group similar to hashtag com-munities (see fluid community, Seargeant/Tagg 2014), that constitute around hashtags because users are attracted by the hashtag (other than e. g. “node communities” that built around a user who befriends the others). This name choice can be interpreted as a practice of authentication to an in-group and, therefore, as face-work.

Phonic-Graphic Aesthetics Continuum: Another important criterion in choosing a username is the perceived aesthetics of a name with regard to its sound or typeface (cf. Aldrin 2011). Which structural characteristics of a name are judged to be aesthetically pleasing depends largely on social factors (Nübling 2017), although personal preference may also play a role (see e. g. Silva/Topolinski 2018). Against the background of the discourse on conceptual orality in the written medium of the internet, two poles for the aesthetic design of usernames seem to emerge: a phonic and a graphic one, which in turn are intertwined with the other continua, particularly the Authenticity-Anonymity continuum.

For example, some users see online communication as conceptually oral (see Dürscheid 2003), which is also evident in their choice of nickname. The user named silkrivers, for example, describes their nickname as “a combination of euphonic sounding words”, which would be irrelevant without the concept of written orality.

By contrast, others focus on the visual aesthetics of the typeface and use features of this new form of literacy (see Androutsopoulos 2007). The Twitter user named @m****l****xo attaches the xo-emoticon to her first and middle name and explains: “'xo' looks nice”.

We believe that analysing linguistic strategies on the basis of decision continua which are shaped by the affordances and restrictions of the respective medium and the communicative needs of the users would be extremely fruitful for future studies. Aside from user-names, this can serve as a stepping stone for systematising other aspects of online face-work in relation to the medium or channel. These decision continua represent an important starting point for interpreting the usernames.

3.2.3 Self-Naming Practices in Other Language Contexts

As part of the international nickname project, comparable (as far as context allowed) questionnaire studies were carried out for seven languages in addition to English: German, Swedish, Luxembourgish, Croatian, Japanese, Chinese and (Moroccan) Arabic (see Schlobinski/T. Siever 2018a). The results of these are similar in many aspects, but also show clear differences relevant for the interpretation of self-naming as a sociolinguistic practice.

For the analysis of British usernames, we asked participants to provide information on their usernames by giving them the following prompt:

Please provide us with some examples of nicknames you use, which platform you use them on and the reasons for choosing this particular nickname. Below, you can find three examples of the kind of information we would like to obtain. If you have any questions, please let me know!

The participants then could add as many usernames as they wanted to the sheet they had been provided with.[10]

In particular, regarding the inclusion of ‘real’ names in usernames, i. e. decision making along the continuum of authentication and anonymization, clear trends and differences emerge.

Whether (parts of) the users’ actual names are included differs greatly depending on the cultural context: Arabic (Tahiri 2018, see chapter 1 in Schlobinski/Siever 2018a), Swedish (Siebold 2018, chapter 13), Luxembourgish (Conrad 2018, chapter 9) and Croatian (Mathias/Pintarić 2018, chapter 8) users’ choices are very similar to those of English users, as their usernames contain at least in part items from the onymic inventory in 59 % of cases. In the German study, only 40 % of usernames contained elements of the onymic inventory of German or parts thereof (Schlobinski/Siever 2018b). In the Japanese study (Oberwinkler 2018, chapter 6) 20 % of the usernames consisted of omyms that are part of the onymic inventory of Japanese, of which only 11.7 % are (most likely) surnames. And the analysis of the Chinese platform Weibo (Zhu/Zhang 2018, chapter 2) found that only 12.4 % of usernames contain what is typically regarded to be part of the respective onymic inventory, 8 % of which appear to be surnames.

How much information (i. e. how many clues as to what the birth or legal name of a user is) there is given therefore differs greatly across different cultural contexts. For example, Oberwinkler (2018: 166), who analysed the Japanese usernames, discusses a study by Orita/Miuri: “In Japan, it is often avoided to specify your own proper name on the internet. One can speak of a widespread resentment (see Orita/Miuri 2011, Orita 2009)”. Positive identity work in Japan is potentially more about anonymization than about authentication and thus favours one end of the Authenticity-Anonymity continuum. Here, as is so often the case, cultural differences are important for the interpretation of the data (Spencer-Oatey 2005). The fact that only very few authentic names are used on the Weibo platform in China has to be interpreted in the context of the political climate as a potential reaction to the policing of digital spaces and the more flexible attitude towards names and naming in general in China.

3.3 Self-naming Practices Online

As argued above, the analysis of self-naming practices on social media strongly suggests that they are a form of face-work. However, for a better understanding of the complex sociolinguistic practices that accompany face-work, we need to include the restrictions and affordances of the respective platform in the interpretation: the dilemma of authenticity and anonymity (Bedijs/Held/Maaß 2014), the collapse of concrete and shared contexts (boyd/Marwick 2011; Wesch 2008) and the users’ ability to de-contextualise and re-contextualise. The following section outlines how the Four Principles of Onomastic Identity Construction can be transferred to the study of naming practices in online environments.

3.3.1 The Four Principles of Online Naming

3.3.1.1 Mono-Referentiality

Names differ from common nouns in that they ideally have only one referent in a particular context, while common nouns can have many referents. In onomastics, mono-referentiality is not necessarily absolute, because two or more people can share the same name.

However, technical restrictions of a particular platform can lead to a need to create a unique, truly mono-referential username. Twitter, for example, has a specific help page addressing, among other things, what to do when a username is already taken; they recommend the use of an underscore, which is one of a number of strategies that users apply – in particular if the username contains the users’ birth or legal (components) (see e. g. Hämäläinen 2013). In these cases, numbers or special characters are often found as additions to the anthroponymic components, as is variation of spelling or the combination of the name with other lexis. If this username uniqueness is generated by adding numbers, age or the year of birth is often preferred over consecutive numbering. Nübling/Fahlbusch/ Heuser (2015) discuss the dehumanising nature of numbering in humans against the background of the common practice of numbering livestock. In livestock as well as in scientific laboratory animals name uniqueness is generated by assigning numbers, because the context demands maximum individualization – similar to the technology of the online platform that enforces name uniqueness. But in contrast to livestock, users choose their numbers freely. There is tentative evidence that the inclusion of numbers does not, for example, influence the “in-out effect” (Silva/Topolinski 2018), but how exactly numbers in user-names are perceived by other users outside marketing and psycho-logical research has to our knowledge not been studied extensively.

3.3.1.2 Self-Representation

In older publications the potential to be able to perform a certain partial identity through a screenname is often regarded to be a driving factor (e. g. Bechar-Israeli 1995; Kaziaba 2013) with the username thus being a vehicle of (emotional) self-expression. This aspect may become less relevant in Web 2.0, not least because the boundaries between online and offline are becoming increasingly blurred. In online gaming, however, there are numerous examples of usernames being used for the expression of partial identities (see Bainbridge 2010).

What is important to many users, however, is that they like the online name themselves. They consciously or subconsciously follow an aesthetic principle, which in turn is also a form of self-expression.

One motivation behind the name choice of users who choose a creative name incorporating e. g. appellatives is thus to follow an aesthetic principle. What is perceived as aesthetic is highly subjective, trends within a given CoP and also depends on the cognitive concept of graphic or phonic aesthetics. In order to devise a creative name in written media, test subjects are often influenced by an orality-oriented concept of communication (see Dürscheid 2003). For example, melancholypeach explained their choice of name by stating “I like the flow of it”, although the name is likely to be written and read more often than spoken out loud.

3.3.1.3 Authentication vs Anomymisation

The use of (parts of) one’s birth or legal name can be considered as a special kind of authentication practice that emphasizes the offline self (see Jacobson 1996, Lindholm 2013), so that the users thus identify themselves as persons with rights and obligations and in order to express closeness.

The information on strategies employed when choosing usernames provided by the informants of our survey of students based in the UK show that it is a multi-layered and multi-dimensional decision-making process. The informants consistently stated that this strategy is used to make their account easier to find for friends and family. Others expressed the view that a higher degree of transparency (i. e. offering at least the potential of being able to relate it back to a real person in an offline context) when choosing names is a sign of openness and authenticity. Many users settle on a compromise between others being able to recognise them through a higher degree of ‘onymicity’ and the protection of privacy through the choice of more opaque appellatives.

Figure 2: Decision continuum between anonymity and authenticity when choosing usernames.

In cases where users decide to adopt a different gender or ethnicity in an online environment such as Second Life, this has been de-scribed as a utilization of the “potential for anonymity” and “identity tourism” (Bullingham/Vasconcelos 2013: 103). Anonymity through adopting a pseudonym that bears no relation to the offline self has also been described as a driving force for users who write under difficult political circumstances or on topics generally regarded as taboo (Aleksiejuk 2016a, b). In a survey by Swennen (2001, cited in Aleksiejuk 2016b: 452) more than half of the participants stated that the driving factor behind choosing a pseudonym was preservation of anonymity. Similarly, in a study by Hämäläainen (2013) where participants were asked to rate usernames, a majority rated nontransparent, mysterious usernames as ‘good’ usernames.

In many contexts, however, an opaque username that preserves anonymity may be perceived as suspicious (Hagström 2012; Heisler/ Crabill 2006) with the absence of authenticating cues being interpreted as suspicious and potentially fraudulent.

3.3.1.4 Individualisation vs. Group Convergence

Identity work in online communities is inherently relevant to users’ sociolinguistic practices in online environments (see e. g. Seargeant/ Tagg 2014 on identity and community online) and group effects such as adaptation and differentiation play an important role in this context (see theories on social identity, Tajfel/Turner 1986). Choosing an appropriate username, e. g. on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube or online gaming platforms, is a form of self-presentation and a means of authenticating oneself as a member of a CoP. The goals of self-presentation vary according to the group and individual. For example, Kaziaba (2016: 24–25) finds in the ego-shooter Counterstrike particularly frequent names related to the game content (Feuerengel ‘fire angel’, Terminator) as well as their persiflage from a satirical distance (Affe mit Waffe ‘monkey with a weapon’, Stirb! ‘Die!’). Evidence for this was provided by our own study on usernames and the stylistics of youth languages and group-related slang (Lotze/ Sprengel/Zimmer 2015). For the Gothic forum nachtwelten.de we find ’mystical’ names with (also partly ironic) references to Gothic subculture (mindshaper, Spooky, carpe_noctem). Feature clusters can also be found in Stommel's (2007) study of usernames in forums about eating disorders: users prefer e. g. usernames that connote lightness, small size or childishness. In a similar vein, Lindholm (2013) analysed usernames of two forums, one on parenthood and one on photography and found that many usernames in the parenting forum emphasize motherhood and femininity (with over a third of usernames in the data explicitly relating to the parenting theme), whereas in the photography forum there were also usernames that index masculinity and less than 10 % of usernames were explicitly photography related.

The four principles of online naming are not mutually exclusive, but rather go hand in hand, since they essentially describe human identity work on different levels: unity with oneself and a mono-referential name, self-expression of partial identities, authentication as a rational agent, and group behaviour.

We argue that all of the above is face-work and that there appear to be discernible strategies that are perpetuated in certain CoPs or by specific individuals and potentially depend on the technical affordances of the respective platforms which warrant further investigation. Users “actively negotiate the material features, or boxes, buttons, and menus, of platforms” (van der Nagel 2017: 326). This means that there has to be media competence to negotiate the complex terrain of social media which is also worthy of further analysis.

4 Final Remarks and Directions for Further Research

We understand online self-naming as a complex and dynamic socio-linguistic practice of authentication or anonymisation, which can be understood as face-work in Goffman’s sense.

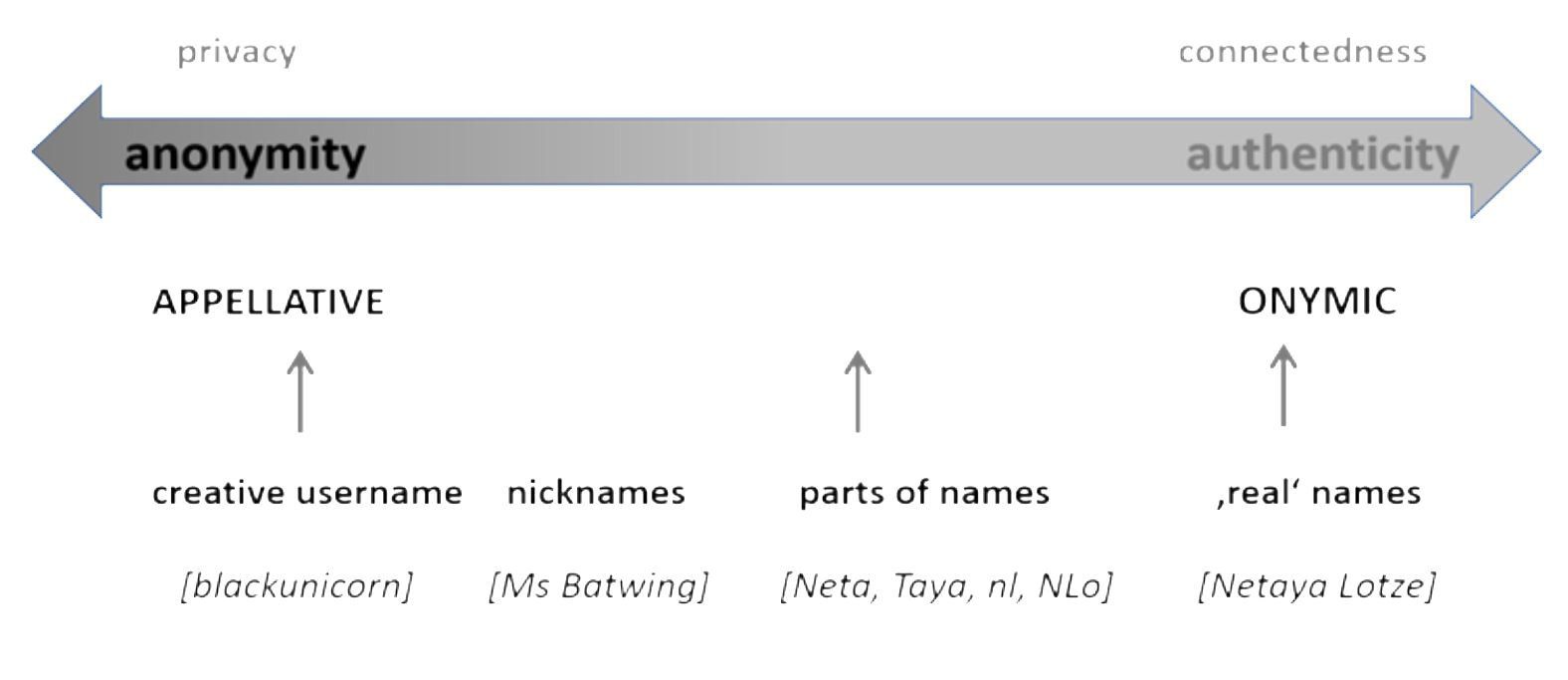

If screennames are interpreted as the positioning of the individual in relation to a community through use of a shared semantic inventory, they cannot be denied a communicative character. But how interactive is linguistic identity work online? (principle of emergence, see Bucholtz/Hall 2005)? The social face was often interpreted as a subject of negotiation in the context of relationship work (see Locher/ Watts 2005). But how are names negotiated in online communities? Androutsopoulos (2006: 525) defines screennames as “acts of self-presentation that are designed and presented to, rather than negotiated with, an audience”. More recently, naming is viewed more like a dynamic than a static concept in onomastics. Evidence comes from studies on name choice in parents (Aldrin 2011) and the transgender community (Schmidt-Jüngst 2018), where names are discussed, tested and altered when transitioning from one gender to another.

When parents name their child, this is usually a dynamic, interactive and highly recursive process in which different possible names are discussed (compare Aldrin 2011).

Figure 3: The process of personal naming (Aldrin 2011: 394).

So, to which degree is self-naming online and self-naming in general a negotiated practice? There is evidence for communities in which the name choice is commented on and discussed by the group, which sometimes leads to a change of name (Bechar-Israeli 1995; Gatson 2011; Lindholm 2013; for gaming: see Bainbridge 2010; Kaziaba 2013, 2018). And in our survey, the vast majority of participants points to some form of name negotiation or change of username in analogy to Aldrin (2011) and Schmidt-Jüngst (2018). This suggests that the principle of emergence after Bucholtz/Hall (2005) applies to online naming, too. Studies that place the interactive nature of identity work through usernames at the heart of their inquiry would provide valuable insights into the co-constructed nature of usernames, not least because Goffman’s notions of face and face-work are ideally suited to illuminate this area of DMI.

References

Aldrin, Emilia (2011): Choosing a Name = Choosing Identity? Towards a Theoretical Framework. In: Generalitat de Catalunya (eds.): Proceedings “Els noms en la vida quotidiana: Actes del XXIV Congrés Internacional dʼICOS sobre Ciències Onomàstiques”. Biblioteca tècnica de politíca lingüística onomàstica, 11. Barcelona, 392–401.

Aleksiejuk, Katarzyna (2016a): Internet Personal Naming Practices and Trends in Scholarly Approaches. In: Puzey, Guy/Kostanski, Laura (eds.): Names and Naming: People, Places, Perceptions and Power. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 5–17.

Aleksiejuk, Katarzyna (2016b): Pseudonyms. In: Hough, Carole (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Oxford: OUP, 438–452.

Aleksiejuk, Katarzyna (2017): Names on the Internet: Towards Electronic Socio-onom@stics. Edinburgh. [Dissertation University of Edinburgh]. URL: http://hdl.haaldrinndle.net/1842/23441.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2003): Medienlinguistik. Beitrag für den Deutschen Fachjournalisten-Verband e. V. URL: https://jannisandroutsopoulos.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/medienlinguistik.pdf.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2006): Multilingualism, diaspora, and the Internet: Codes and identities on German-based diaspora websites. In: Journal of Sociolinguistics, 10, 520–547.

Androutsopoulos, Jannis (2007): Neue Medien – neue Schriftlichkeit? In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Germanistenverbandes 54 (1), 72–97.

Angouri, Jo (2015): Online communities and communities of practice. In: Georgakopoulou, Alexandra/Spilioti, Tereza (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Language and Digital Communication. London: Routledge, 323–338.

Antos, Gerd (2004). Namenwahl: Ein biographisches Streiflicht. In: Bulletin VALS-ASLA 80, 21–25.

Bainbridge, William Sims (2010): The Warcraft Civilization: Social Science in a virtual World. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

Baron, Naomi S. (2008): Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World. Oxford: OUP.

Barton, David/Lee, Carmen (2013): Language Online: Investigating digital texts and practices. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bechar-Israeli, Haya (1995): From <Bonehead> to <cLoNehEAd>: Nicknames, play, and Identity on Internet Relay Chat. In: Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 1–2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1995.tb00325.x.

Bedijs, Kristina/Held, Gudrun/Maaß, Christiane (2014): Introduction: Face Work and Social Media. In: Bedijs, Kristina/Held, Gudrun/Maaß, Christiane (eds.): Face Work and Social Media. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 9–28.

Beißwenger, Michael (2007): Sprachhandlungskoordination in der Chat-Kommunikation. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter.

boyd, danah/Marwick, Alice (2011): Social privacy in networked publics: teens’ attitudes, practices and strategies. Presentation at Decade in Internet Time: Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and Society, September 2011, URL: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1925128.

Bucholtz, Mary/Hall, Kira (2005): Identity and interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach. In: Discourse Studies 7 (4–5), 585–614.

Bullingham, Liam/Vasconcelos, Ana C. (2013): ‘The presentation of self in the online world’: Goffman and the study of online identities. In: Journal of Information Science 39 (1), 101–112.

Conrad, François (2018). Luxemburgisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 241–262.

Crystal, David (2001, new edition 2010): Language and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Del-Teso-Craviotto, Marisol (2008): Gender and sexual identity authentication in language use: the case of chat rooms. In: Discourse Studies 10, 251–270.

Dürscheid, Christa (2016): Nähe, Distanz und neue Medien. In: Feilke, Helmuth/Hennig, Mathilde: Zur Karriere von ‚Nähe und Distanz‘. Rezeption und Diskussion des Koch-Oesterreicher-Modells. Berlin: De Gruyter, 357–385.

Dürscheid, Christa (2007): Private, nicht-öffentliche und öffentliche Kommunikation im Internet. In: Neue Beiträge zur Germanistik 6(4), 22–41.

Dürscheid, Christa (2003): Medienkommunikation im Kontinuum von Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit. Theoretische und empirische Probleme. In: Zeitschrift für Angewandte Linguistik 38, 37–56.

Durvasula, Ramani (2016): We live in the age of #narcissism. Podcast. URL: https://twitter.com/doctorramani/status/741274446460112910.

Erikson, Erik H. (1974): Identität und Lebenszyklus: Drei Aufsätze. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Fernandes Soares, Rute Isabel (2018). Portugiesisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 287–310.

Franco Barros, Mario (2018). Spanisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/ Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 351–379.

Fröhlich, Uta (2014): Reflections on the psychological terms self and identity in relation to the concept of face for the analysis of online forum communication. In: Bedijs, Kristina/Held, Gudrun/Maaß, Christiane (eds.): Face Work and Social Media. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 105–128.

Gatson, Sarah N. (2011): Self-Naming Practices on the Internet: Identity, Authenticity, and Community. Cultural Studies <->. In: Critical Methodologies 11, 224–235.

Goffman, Erving (1981): Forms of Talk. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goffman, Erving (1967): Interaction Ritual: Essay on Face-to-Face Behaviour. New York: Anchor Books.

Graham, Sage (2015): Relationality, friendship, and identity in digital communication. In: Georgakopoulou, Alexandra/Spilioti, Tereza (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Language and Digital Communication. London: Routledge, 305–320.

Haase, Martin/Huber, Martin/Krumeich, Alexander/Rehm, Georg (1997): Internetkommunikation und Sprachwandel. URL: http://georg-re.hm/pdf/Haase-et-al.pdf, [11.02.2019].

Habermas, Jürgen (1993): Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. Band 1. Handlungsrationalität und gesellschaftliche Rationalisierung. 2 Bände. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Hagström, Charlotte (2012): Naming Me, Naming You. Personal names, online signatures and cultural meaning. In: Helleland, Botolv/Ore, Christian-Emil/ Wilkstrøm, Solveig (eds.): Names and Identities, Oslo Studies in Language 4, 81–93.

Hämäläinen, Lasse (2013): User Names in the online gaming forum Playforia. In: Sjöblom, Paula/Ainiala, Terhi/Hakala, Ulla (eds.): Names in the Economy: Cultural aspects. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 214–228.

Hansack, Ernst (2004): Wesen des Namens. In: Brendler, Andrea/ Brendler, Silvio (eds.): Namenarten und ihre Erforschung. Ein Lehrbuch für das Studium der Onomastik. Lehr und Handbücher zur Onomastik. Bd. I. Hamburg: baar, 51–65.

Hegelich, Simon/Shahrezaye, Morteza (2015): The Communication Behavior of German MPs on Twitter: Preaching to the Converted and Attacking Opponents. European Policy Analysis (EPA) 1 (2), 155–174.

Heisler, Jennifer M.,/Crabill, Scott L. (2006): Who are “stinkybug” and “Packerfan4”? Email Pseudonyms and Participants’ Perceptions of Demography, Productivity, and Personality. In: Journal of computer-mediated communication 12 (1), 114–135.

Herring, Susan C./Stein, Dieter/Virtanen, Tuija (eds.) (2013): Handbook of pragmatics of computer-mediated communication. Berlin: Mouton.

Herring, Susan C. (1996): Computer-Mediated Communication: Linguistic, Social and Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hölig, Sasha (2018): Eine meinungsstarke Minderheit als Stimmungsbarometer?! Über die Persönlichkeitseigenschaften aktiver Twitterer. In: Medien & Kommunikationswissenschaft 66 (2), 140–169.

Jacobson, David (1996): Contexts and Cues in Cyberspace: The Pragmatics of Naming in Text-Based Virtual Realities. In: Journal of Anthropological Research, 52 (4), 461–479.

Kant, Immanuel (1999): Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten. Herausgegeben von Bernd Kraft und Dieter Schönecker. Hamburg: Meiner.

Kaziaba, Viktoria (2013): Namensmasken im Internet. Anthroponymika in der deutschsprachigen ICQ-Kommunikation. In: Muttersprache 4, 327–338.

Kaziaba, Viktoria (2016): Nicknamen in der Netzkommunikation. In: Der Deutschunterricht 68 (1), 24–28.

Kaziaba, Viktoria (2018): Russisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 311–330.

Kersten, Saskia/Lotze, Netaya (2018): Englisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 101–124.

Keupp, Heiner/Ahbe, Thomas/Gmür, Wolfgang (2002): Identitätskonstruktionen: Das Patchwork der Identitäten in der Spätmoderne. Reinbeck: Rowohlt.

Kim, Hojin (2018). Koreanisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 191–220.

Koch, Peter/Oesterreicher, Wulf (1985): Sprache der Nähe - Sprache der Distanz. Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgeschichte. In: Jakob, Daniel/ Kablitz, Andreas/Koch, Peter/König, Bernhard/Küpper, Joachim/ Schmitt, Christian (eds.): Romanistisches Jahrbuch 36. Berlin/ New York: De Gruyter, 15–43.

Lasswell, Harold. D. (1948): The Structure and Function of Communication in Society. In: Bryson, Lyman (ed.): The Communication of Ideas. A Series of Addresses. New York: Harper/ Brs., 32–51.

Lave, Jean/Wenger, Etienne (1991): Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: CUP.

Lawson, Edwin D. (2016): Personal Naming Systems. In: Hough, Carole (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 169–198.

Lettmaier, Saskia (2015): Personennamen und Recht in Großbritannien aus rechtswisschenschaftlicher Sicht. In: Namenskundliche Informationen 105/106, 147–167.

Lindholm, Loukia (2013): The maxims of online nicknames. In: Herring, Susan C./Stein, Dieter/Virtanen, Tuija (eds.): Pragmatics of Computer-Mediated Communication. Berlin: De Gruyter, 427–461.

Locher, Miriam A./Watts, Richard J. (2005): Politeness theory and relational work. In: Journal of Politeness research 1 (1), 9–33.

Locke, John (1975): An Essay concerning Human Understanding Edited with an introduction, critical appartus and glossary by Peter H. Nidditch. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lotze, Netaya/Kersten, Saskia (2020): Nicknamen zwischen Anonymität und Wiedererkennungswert. In: Calderón, Marietta/Herling, Sandra (eds.): Namen Digital. Zeitschrift für Österreichische Namenforschung.

Lotze, Netaya/Kersten, Saskia (under review): Methoden der Internet-Onomastik – Zur kontrastiven Analyse von Nicknamen. In: Tienken, Susanne/Hauser, Stefan/Lenk, Hartmut/Luginbühl, Martin (eds.): Methoden kontrastiver Medienlinguistik. Sprache in Kommunikation und Medien. Bern: Lang.

Lotze, Netaya (2016): Chatbots – Eine linguistische Analyse. Hamburg: Lang.

Lotze, Netaya/Sprengel, Sebastian/ Zimmer, Anne (2015): Rückgriffe auf ‚dunkle‘ Zeiten? Zur Verwendung historischer Ausdrücke in jugendsprachlichen Subkulturen. In: Der Deutschunterricht 67 (3), 38–47.

Marx, Konstanze (2017): Diskursphänomen Cybermobbing. Ein internetlinguistischer Zugang zu (digitaler) Gewalt. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Mathias, Alexa/Pavić Pintarić (2018). Kroatisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 221–240.

Mead, George Herbert (1978): Geist, Identität und Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Moraldo, Sandro M. (2018). Italienisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/ Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 125-160.

Nicolaisen, W. F. H. (1999): An Onomastic Autobiography, or, In the Beginning Was the Name. In: Names 47 (3), 179–190. DOI: 10.1179/nam.1999.47.3.179.

Nübling, Damaris/Fahlbusch, Fabian/Heuser, Rita (2015): Namen: Eine Einführung in die Onomastik. Tübingen: Narr.

Nübling, Damaris (2017): Beziehung überschreibt Geschlecht. Zu einem Genderindex von Ruf- und von Kosenamen. In: Linke, Angelika/Schröter, Juliane (eds.): Sprache und Beziehung. Berlin/ Boston: De Gruyter, 99–118.

Obwerwinkler, Michaela (2018): Japanisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/ Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 161–190.

Orita, Akiko 折田明子/Miura, Asako 三浦麻子 (2011): ネットコミュニティの利用者の名乗りとアイデンティティ-「発言小町」利用者調査分析(2) 利用姿勢と実名・仮名・匿名 Identity and Screen-name of Users of Online Community Survey on “Hatsugen-Komachi”: Attitude towards Real-name, Pseudonym and Anonymity. URL: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jasmin/2011f/0/2011f_0_85/_pdf

Orita, Akiko 折田明子 (2009): ネット上のCGM利用における匿名性の構造と設計可能性 Structure and Design of Anonymity on the Internet. In: 情報社会学会誌 4 (1) 原著論文 Jōhō shakai gakkaishi 4(1), 5–14.

Pickering, Martin/Garrod, Simon (2004): Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. In: Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27 (2), 169–190.

Pörksen, Bernhard (2005): Die Konstruktion von Feindbildern. Zum Sprachgebrauch in neonazistischen Medien. Wiesbaden: VS.

Radford, Marie L./Radford, Gary P./Connaway, Lynn S./DeAngelis, Jocelyn A. (2011): On Virtual Face-Work: An Ethnography of Communication Approach to a Live Chat Reference Interaction. In: The Library Quarterly 81 (4), 431–454.

Runkehl, Jens/Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (1998): Sprache und Kommunikation im Internet. Überblick und Analysen. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Schlobinski, Peter (2012): Sprache und Kommunikation im Digitalen Zeitalter. Rede anlässlich der Verleihung des Konrad-Duden-Preises der Stadt Mannheim am 14. März 2012. URL: https://ids-pub.bsz-bw.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/40/file/Schlobinski_Sprache_und_Kommunikation_im_digitalen_Zeitalter_2012.pdf, [11.02.2019].

Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (2018a): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt a.M. etc.: Lang.

Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (2018b). Deutsch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 77–100.

Schmidt-Jüngst, Miriam (2018): Der Rufnamenwechsel als performativer Akt der Transgression. In: Nübling, Damaris/Hirschauer, Stefan (eds.): Namen und Geschlechter: Studien zum onymischen Un/doing Gender. Berlin: De Gruyter, 45–72.

Seargeant, Philip/Tagg, Caroline (2014): Introduction: The language of social media. In: Seargeant, Philip/Tagg, Caroline (eds.): The Language of Social Media. Identity and Community on the Internet. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–20.

Siebold, Oliver (2018). Schwedisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 331–350.

Siever, Christina Margrit (2018). Niederländisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever,Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 263–286.

Siever, Torsten (2006): Sprachökonomie in den ‚Neuen Medien‘. In: Schlobinski, Peter (ed.): Von »hdl« bis »cul8r«. Sprache und Kommunikation in den neuen Medien. Mannheim: Dudenverlag. 71–88.

Silva, Rita R./Topolinski, Sascha (2018): My username is IN! The influence of inward vs. outward wandering usernames on judgments of online seller trustworthiness. In: Psychology/Marketing 35, 307–319. DOI: 10.1002/mar.21088.

Sifry, Micah L. (2011): WikiLeaks and the Age of Transparency. New York: ORBooks.

Spencer-Oatey, Helen (2005): Relational Concerns in Intercultural Workplace Teams: Theoretical Insights from the Study of Emotions. URL: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/al/people/spencer-oatey/spencer-oatey_h/interpersonal_relations.pdf, [28.06.2018].

Stommel, Wyke (2007): Mein Nick bin ich! Nicknames in a German Forum on Eating Disorders. In: Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13, 141–162.

Swennen, Geert (2001): Identiteit in computer-mediated communications: Een analyse van nicknames. Licentiate dissertation, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

Szurawitzki, Michael (2010): Wie lässt sich Sprache in sozialen Internet-Netzwerken untersuchen? Grundlegende Fragen und ein Vorschlag für ein Analysemodell. In: Muttersprache 120, 40–46.

Tagg, Caroline (2015): Exploring Digital Communication: Language in Action. London: Routledge.

Tajfel, Henri/Turner, John C (1986): The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel, Stephen/Austin, William G. (eds.): Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall, 7–24.

Tahiri, Naima (2018). Arabisch. In: Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (eds.): Nicknamen international: Zur Namenwahl in sozialen Medien in 14 Sprachen. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 29–56.

Thomas, Angela (2007): Youth Online: Identity and Literacy in the Digital Age. New York/Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

Turkle, Sherry (2012): Wir müssen reden. Laptops, Smartphones, Tablets. Die digitale Technik verändert nicht nur unsere Kommunikation – sie verändert uns. Die Zeit, 03/05/2012, 11.

Twenge, Jean/Campbell, Keith (2009): The narcissism epidemic. Living in the Age of Entitlement. New York: Ataria.