Vol 2 (2019), No 2: 195–235

DOI: 10.21248/jfml.2019.21

Discussion paper available at:

http://dp.jfml.org/2019/opr-oloff-some-systematic-aspects-of-self-initiated-mobile-device-use/

Some systematic aspects of self-initiated mobile device use in face-to-face encounters

Abstract

This paper investigates self-initiated uses of mobile phones (such as texting or making a call) in everyday video-recorded conversations among Czech speakers. Using ethnomethodological conversation analysis, it illustrates how participants publicly frame their own device use (for example, by announcements), and how co-present interlocutors respond to it. Previous studies have described how participants manage two concurrent communicative involvements, but have not provided detailed sequential descriptions of how device use can be negotiated and accounted for. This study shows that mobile device use in co-presence is not a priori problematic (or vice versa). Instead, participants frame their technology use in different ways according to various features of the social situation they treat as momentarily relevant. These features include the course of the conversation and how the device use relates to it, the overall participation framework and the opacity of the device use for co-present others.

Keywords: conversation analysis, multimodal analysis, ordinary conversation, mundane technology use, smartphones, announcements, accounts

1 Introduction

This paper investigates self-initiated uses of mobile devices – mobile phones or smartphones – in video-recorded face-to-face encounters. Exploiting the analytical framework of ethnomethodological conversation analysis, it illustrates when and how participants publicly frame their own device use, and how co-present others respond to it. While early sociological accounts of public mobile phone use described how both phone users and non-users observably reacted and adapted to practices involving mobile devices, a systematic description of recurrent patterns of “public” mobile phone use still remains to be established. Via a sequential and multimodal analysis of videotapes of ordinary conversations in Czech, this contribution will analyse how participants self-initiate a mobile device-related activity such as texting or making a phone call in the co-presence of others. It will be argued that the presence or absence of a verbal announcement of an individual’s mobile device use, as well as the co-participants’ responses to this, cannot be simply or unequivocally linked to the type of device use and its potential “intrusiveness”. Both phone users and non-users negotiate and orient towards other interactionally relevant features as well, such as the sequential fittedness of the device use with regard to the on-going encounter, the device user’s current involvement in this encounter, or the potential opacity of the device use for co-present others.

Early studies focused on mobile device use in freely accessible and anonymous public spaces, employed fleeting observations of and reported claims about problematic mobile device use, and usually connected it to an assumed overall social order (Section 2.1). This paper adopts an alternative approach to “socially problematic” mobile device use by investigating the individual handling of a mobile device as a public and accountable practice in focused encounters (in both public and private settings), and by describing how participants systematically manage practical problems of diverging orientations and activities in the co-presence of others (Section 2.2). Based on video recordings and transcripts of naturally occurring social encounters in Czech, this contribution adopts a conversation analytic perspective on divergent mobile phone use in face-to-face encounters; that is, use that is not framed as a joint activity, but as an individual action trajectory of a single participant. The analyses will contribute to a more recent line of interactional research on mobile phones in face-to-face encounters (Section 2.3) by focusing on the initiation of classic types of device use in the co-presence of others, such as writing a text message (Sections 3.1, 3.2) or making a phone call (Section 3.3). The adopted sequential and multimodal approach reveals that even divergent mobile device use is not treated a priori as problematic. Participants can (but do not automatically do) account for their individual device use by formulating an “announcement sequence”. The analysis aims to reveal when and how these sequences emerge, and how the participants’ choices are consequential for the management of multiple action trajectories (Section 4).

2 Sociological and interactional accounts of mobile telephones: Public perceptions of “private” communication and use

The tension between “public” and “private” communication settings was already recognised as a problematic issue in the time of landline phones (Höflich 1996: 195–231; Pool 1977, see also König/Oloff 2019). However, this did not spark extensive sociological interest (Fischer 1992), probably because it was perceived as already being a fully domesticated technology (Berker 2006; Höflich 2009: 65–69; Silverstone/Haddon 1996). In contrast, the appearance of the mobile phone was met with immediate academic enthusiasm; at first, mainly with regard to its general perceivable uses in public spaces (Section 2.1) and, more specifically, in relation to the tension between social encounters in co-presence and involvement with the device (Section 2.2). More recently, research has increasingly become focused on the detailed management of talk-in-interaction and concurrent device use (Section 2.3).

2.1 A new observable practice in public spaces

While other personal mobile devices have been used in public spaces previously (for example, the Walkman; DuGay et al. 1997; Goggin 2006: 6–10), mobile phones generated far more scientific output. In fact, it was not the most evident innovation itself, the mobility of the device, that motivated early ethnographic observations and descriptions, but rather the mere visibility and audibility of a new communication practice in public spaces. The metaphor of privacy somehow seeping into the public space and life (often referring to Sennett 1977), in which the mobile phone seems to act autonomously, was particularly popular in earlier studies:

Much has been asked about whether cell phones privatize public spaces or publicize private spaces. This is the same case of whether the cell phone is responsible for taking one in or out of physical space: the borders have been blurred and it is hard to define what is private and what is public. The very concepts of private and public have been transformed. (de Souza e Silva 2006: 33)

The now spatially independent reception or initiation of phone calls in public spaces has led to two fundamental practical problems with regard to social conduct in co-presence. Firstly, how do phone users manage their physical presence and on-going activity with regard to their sudden involvement with the phone? Secondly, how do co-present others react appropriately to and coordinate with this potentially competitive involvement? Particularly in earlier studies, the use of mobile phones was represented (both by researchers and by respondents) as entering into conflict with the usual social norms and conduct in public: A phone can ring at unpredictable and unsuitable moments, trigger psychological or emotional stress, and disrupt on-going face-to-face interactions (Cumiskey 2005; Höflich 2009; Katz 2006), leaving “bystanders helplessly waiting” (Geser 2004: 22). Co-present parties are possibly annoyed at being forced to listen to phone calls that are “acts of unreciprocated communication” (Katz 2006: 44), that reveal information that bystanders may not wish to know, and that the phone user might not want to reveal (Ling 2008: 93–95). Although the commonplace vision of the “intrusiveness” of the mobile phone has also been criticised (Lasén 2005: 41), it is widely assumed in early studies of public mobile phone use (Geser 2005; Höflich/Kircher 2010; Kopomaa 2000; Ling 1997; 2008: 57–72; Persson 2001; Plant 2001).

2.2 Managing two concurrent interactional involvements

The problematic character of public mobile phone use has essentially been linked to the fact that phone users “occupy multiple social spaces simultaneously” (Palen et al. 2001: 110); in other words, the physical space of the phone user and the “virtual space of the conversation” (Palen et al. 2000: 209). This leads to different types of observable social conduct: Phone users actively seek an appropriate space to make a call by turning or moving their bodies away from co-present others, possibly formulating an apology (Geser 2004; Lasén 2005: 94). They frequently withdraw their gaze from their co-present interlocutors; and their eyes can wander around or be directed into the distance (Plant 2001: 53). Co-present participants, for their part, do usually not gaze at phone callers; they turn their bodies away from the caller or retreat to a different area (Lasén 2005: 94; Ling 2004: 135–136; Murtagh 2002). Alternatively, they might find some other task in order to displace their attention (Plant 2001: 34). If co-present participants choose to sanction public phone use, they can do so by ostensibly turning their heads to the phone user, by sighing, by looking at them “disapprovingly”, or even by commenting negatively about the phone use, addressing either the phone user or other bystanders (Ictech 2019: 35–40; Lasén 2005: 78; Ling 1997; Okabe/Ito 2005; Plant 2001: 32–34).

This diversity of practices among phone users and bystanders is connected to variations in spaces or in cultures, and/or to a development in user norms and attitudes. Participants are more likely to use their phones in “transitory” spaces – typically public transport (Lasén 2006; Paragas 2005; Schlote/Linke 2010) – than in spaces in which highly ritualised forms of interaction take place (Geser 2004: 26; Höflich 2009; 2014). The acceptability of public phone use is also considered to depend on distinctions between “indoor” (shops, bars, cafés and restaurants) and “outdoor” settings (streets and places; see also Lasén 2005: 70–94; Ling 1997; Taylor 2005), and the degree of formality of a given space (such as different types of restaurants, Plant 2001: 36–38, or institutional settings such as schools, Ling/Yttri 1999; Taylor 2005: 160–163). Some studies have also investigated differences according to countries or global cultural zones (Höflich 2005; Katz/Aakhus 2002; Lasén 2005; Plant 2001; Rivière/Licoppe 2005). In an early study involving nineteen new mobile phone users, Palen et al. (2000) noted that people quickly adopted different perceptions regarding public mobile phone use, which became more acceptable once they began to use mobile phones themselves (Plant 2001: 31). Lasén (2005) also observed that participants in different European countries modified their phone use within a timespan of only two years (2002–2004): They used their phones for longer periods and more frequently, engaged in more multi-tasking (such as texting while walking or phoning while pushing a bike; Lasén 2005: 52), and displayed their emotions while talking on the phone more explicitly (Lasén 2005: 89). They also tended to remain in the participation framework of an on-going face-to-face interaction when making a call more frequently, and were described as listening to co-present parties while texting, such as by making short comments to co-present others while being on the phone (Lasén 2005: 96–98), or such as using loudspeakers in order to allow others to participate in a phone call (Lasén 2006). More detailed observations of public phone use therefore reveal that participants frame and respond to such use in situated and flexible ways, and that handling the double involvement seems to become less problematic over the course of time.

Despite some attempts to draw a more balanced picture of public mobile phone use, early studies focused mainly on a dichotomic view of public/private spaces and of phone users/non-phone users. On one hand, this could be related to the type of data, as most of the aforementioned studies used ethnographic and anonymous observations or variations of breaching experiments in public spaces, and have sometimes also used interviews or focus groups. On the other hand, the analyses have relied mainly on reported practices and traditional sociological concepts (such as of the city, of public space and of social conduct). While this resulted in important descriptions of early mobile phone adoption and use, more detailed explorations of the specific ways in which mobile phone use may intrude in on-going interactions, and how the participants manage this double orientation, were only developed later.

2.3 Mobile phone use in talk-in-interaction

Early mobile phone users have typically been observed and conceived of as isolated actors, even though collaborative uses have been occasionally described, such as sharing the phone and media content on the phone with remote (Oksman 2006) or co-present participants (Relieu 2008; Taylor/Harper 2003; Taylor 2005: 156; Weilenmann/Larsson 2002; see also Suderland 2020). In tandem with the increasing number of mobile device users and the growing frequency of use in recent years, sociological interest has noticeably turned to more differentiated questions. As mobile device use has now infiltrated all types of situations and settings of everyday social practice, it has become available for more systematic and fine-grained observation, particularly within the framework of conversation analysis (Sacks et al. 1974) via the use of audio/video data of naturally occurring interactions and detailed transcripts of talk and embodied conduct (Mondada 2013a; 2016). In this approach, the question of how co-present participants sequentially manage the double involvement of the on-going interaction and their phone use has recently been addressed in more precise ways. Studies have illustrated, among other things, how smartphones are exploited for topical development in conversations (Keppler 2019; Porcheron et al. 2016), how they are used to conduct collaborative searches (Brown et al. 2013; 2015; Suderland 2020), how responses to incoming text messages are related to different discourse identities (DiDomenico et al. 2018), or how showing sequences of media content are initiated and carried out (Oloff 2019a; Porcheron et al. 2016; Raclaw et al. 2016).

While earlier research pointed out the overall and intrinsic problematicity of mobile device use and focused mainly on reported moral aspects, the first micro-analytical studies of coordination between talk and device use, and of the situated negotiation of related moral aspects, have been established more recently (see Robles et al. 2018). Research within the tradition of conversation analysis has concerned the management of joint coordination; therefore, collaborative or “convergent” uses (Brown et al. 2013) of mobile devices have been considered more frequently. By contrast, “divergent uses”, which occur when the mobile device use is disconnected from the on-going conversation (Brown et al. 2013), have more rarely taken centre stage within this approach. Mantere and Raudaskoski (2017) analysed how a participant attempted to overcome the pervasiveness of the “sticky media device”, and struggled to attract a smartphone user’s attention and response. DiDomenico and Boase (2013) showed how a participant shifted her attention back and forth between the face-to-face interaction and her texting activity (also see DiDomenico et al. 2018). By turning to her phone at sequence endings and suspending the use in response to her co-participant’s summons, the phone user clearly demonstrated that she treated the on-going interaction as the “primary involvement” and texting as the “secondary involvement”. Finally, in their study of mobile phone use in pubs, Porcheron et al. (2016) concluded that using a mobile device in co-presence with others remained problematic, as this frequently led to “[…] interruptions, recapitulations of the conversation for members re-joining, displays of attentiveness despite ostensible inattentiveness, and prompts of absent-minded members” (Porcheron et al. 2016: 1657). The authors also noted that participants provided a verbal account, particularly for “unrelated device use” (that is, not connected to the conversation; see the “divergent uses” mentioned by Brown et al. 2013), and thus “[…] make their device interaction both observable and reportable to the other members within the setting” (Porcheron et al. 2016: 1654).[1] The results of the latter contributions hint at the need to describe the organisation of the device-related double involvements more extensively; for example, on which grounds do phone users give preference to one or the other activity, and which interactional details reveal whether the participants regard the device use as interactionally problematic?

Concerning the participants’ orientation to the accountability of the phone use, to date, only a few verbal actions have been described as ways to account for involvement with technology. Apologies could be thought of as being the most prototypical accounts (see Geser 2004; Lasén 2005), but other types of verbal turns can also serve this purpose (Porcheron et al. 2016). While formulating what one will do, is doing or has done with a mobile device can all be understood as tackling the accountability of technology use in a general sense, these different temporalities (before using the device, while using it and retrospectively) obviously imply different accountables and can thus be expected to differ in format. Explicit descriptions of the action to be carried out on the phone are in the initial position (for example, comments such as “I’m going to look for it” that announce and initiate a searching activity on a smartphone, Keppler 2019: 179; Suderland 2020: 102–111), while online comments and reading elements from the screen typically accompany a specific use (in the sense of an “online commentary”, see Suderland 2020: 111–116; see also Porcheron et al. 2016: 1655, fragment 5). In late or post-position, accounts refer to why a device has been used previously (for example, apologies; Porcheron et al. 2016: 1654, fragment 3). However, these different types of verbal turns related and referring to smartphone use have not yet been subject to a differentiated analysis. In most of the cases described in the previously quoted studies, the mobile device will become relevant for joint action at some point, as in the case of smartphone-based showings. If the mobile device is merely used for an individual activity, phone users have been described as formulating “statements” about the imminent suspension of focused interaction (Ictech 2019: 38). As this paper focuses on self-initiated uses of phones, I will take a closer look at these possible “statements” or “announcements” of individual mobile device use. While announcements are typically connected to informings or the delivery of news in the conversation analytic literature (Pomerantz 1984; Terasaki 2004), announcements foreshadowing a specific mobile device use have different practical and sequential implications, as will be shown in the analysis and in the final discussion (Sections 3. and 4.).

3 Analysis

This section will illustrate the interactional features that constitute the way in which participants frame their own smartphone use and the way in which co-participants respond to it. The analysis is based on a number of excerpts from different data sets that were video recorded – with the participants’ informed consent – between 2013 and 2016[2] in cafés and pubs, or in the participants’ homes. The participants were well acquainted with each other and did not receive any instructions with regard to conversational topics, structures or the length of the recording (see Mondada 2013b). The analytical work on which this contribution is based considered both Czech and German data (Oloff 2019b) but, for the sake of clarity, it will focus on Czech examples (for excerpts of the German data, see Oloff 2019a).

The data were transcribed according to the Jeffersonian conventions (Jefferson 2004). The multimodal annotations were made according to Mondada’s conventions (Mondada 2016),[3] and screen captures of the recordings depicting relevant postures or actions are positioned in the transcripts using “#” and continuous numbers within each transcript. In the transcripts, the original Czech talk is presented in black, the idiomatic translation to English in blue, and the multimodal annotations in grey. All proper names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

A fine-grained multimodal approach, considering both the sequential and the embodied dimensions of the social encounters (Deppermann/Streeck 2018; Goodwin 1981; Streeck et al. 2011), was used to examine the verbal turn formats and embodied actions that preceded and accompanied the self-initiated mobile device use. The excerpts, in which one co-participant initiated the writing of a text message (Sections 3.1, 3.2) or a phone call (Section 3.3), exemplify that both mobile device users and co-present others can orient towards the relevance of, for example:

• the channel or “technology” used (call/SMS/internet, audible/non-audible/visible),

• the topical and sequential fittedness of the device use with respect to prior and on-going talk,

• the participant constellation (dyadic/multi-party) and specific membership categories,

• the opacity of what is done with the mobile device, and/or

• the possible opacity of how the device use is multimodally framed by its holder.

The analysis will be followed by some general reflections concerning how the participants organised the management of multiple action trajectories with regard to personal mobile devices. Moreover, it will illustrate how a detailed multimodal perspective on such moments can reveal fundamental sequential mechanisms of normative orientations in mobile device use, which have been acknowledged, but not yet described in detail (see Section 2).

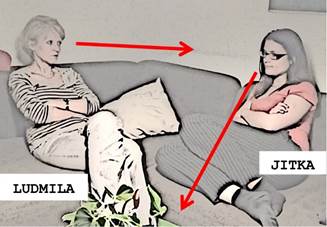

3.1 Writing a text message in co-presence

The first excerpt illustrates how one of the participants in a dyadic interaction self-initiates the writing of a text message. In the family’s home, Jitka (J), and her mother, Ludmila (L), are discussing various topics such as the daughter’s study and holiday plans and the mother’s past student life. Before the beginning of the excerpt, Ludmila enquired about the study curriculum of one of Jitka’s friends, who studied both at the university and at the French Institute (002–011). While Ludmila expands on this topic, it has already come to a possible end, as the pauses and Jitka’s delayed answer indicate (001, 005–006). Jitka simultaneously withdraws her gaze from her mother (006, Figure 1) and begins to look at the table, at the spot where her mobile phone is lying, and seizes it soon thereafter (007–008, Figure 2). In the rest of the excerpt, Jitka explicitly accounts for her disengagement from the joint conversation commenting constantly on her writing of a text message to a friend, thus continuing to interact with Ludmila.

Transcript (1): BOL_SMS_002720

|

001 |

|

(1.5) |

|

002

003

004 |

L

l j |

a jak to, že vona studuje na and how come that she is studying at the institutu- já myslela že studuje na .h institute I thought she is studying at .h (0.3) *univerzitě +ne; (0.3) the university isn’t she *...gaze J----------->014 >>gaze down-----------+..gaze L-> |

|

005 |

|

(0.6) |

|

006 |

J

j |

.th .h + no,#1 .th .h well, >gaze L+..gaze to table/in front-> |

|

|

|

Figure #1 |

|

007 |

j |

(0.9)+(0.2) +..dissolves posture--> |

|

008

009

|

J

j

j |

ne; na francouzském institutu=ONA už tos#2 no at the French institute=she’s already >---reaches for phone, bends forward-----> tou+ univerzitou#3 skončila; finished with university +..gaze L while retracting to sofa-> |

|

|

|

Figure #2 Figure #3 |

|

010 011 |

J

j |

(0.8) °ona už toho nechala.°#4 she already left it >--holds phone in hands, turns screen-> |

|

|

|

Figure #4 |

|

012 |

L |

°mhm_hm,° |

|

013

014

015 |

J

j j

l |

+.h >hele +víš co mi došlo,< že jsem .h listen y’know what I’ve realised that I +...gaze down/phone------------------>037 +button/unlocks screen, taps--> nenapsala Ev*ě Černo*vé=já ji °budu muset haven’t written to Eva Černová=I will have to >gaze J-----*J’s phone*..gaze J-----> asi napsat.°#5 (.) rychlou esemesku. probably write her (.) a quick SMS |

|

|

|

Figure #5 |

|

016 |

L |

°proč,° why |

|

017 |

J

l |

.h: °že jsem ji měla vol*at.° .h: that I had to call her >gaze J-----------------*,,, |

|

018 |

|

(0.6) |

|

019 |

L

j |

°mhm° °tak (.) ji napiš es°emesku+ že,° mhm so (.) write her an SMS that >phone in lap--------------------+..lifts> |

|

020 |

J |

já ji napíšu [rychle:, ]#6 I’ll write her [quickly ] |

|

021 |

L

j l |

[*°nemáš čas(h),°]+he,* [you don’t have tim(h)e]he, >brings phone&hands in position+starts SMS >gaze in front--*..gaze J------------*,,, |

|

|

|

Figure #6 |

|

022 |

|

(0.4) |

|

023

024 |

J

j l |

.th:: (1.0) °prosím°*(0.3) tě .th:: (1.0) hi (0.3) there >taps on display / writes SMS----------> *..gaze J-------->029 (0.9) brou::,(.) čin:; (0.2) ku:, (0.9) <babe ((‘little beetle’))> |

|

025 |

|

(0.3) |

|

026 |

L |

no pr(h)os(h)ím t(h)ě well r(h)eall(h)y |

|

027 |

J |

°zas-° °agai-° |

|

028 |

L |

°.h .he h:° ty ji píšeš broučINku; jo °.h .he h:° you really write babe to her |

|

029 |

J

l |

°°.h: .th::°° no,* °°.h: .th::°° yes >gaze J----------*,,, |

|

030 |

|

(0.7) |

|

031 |

J |

[za:vo:lám ]#7 zí:tra: [I will call ] tomorrow |

|

032 |

L |

[he, he; .hf: (.) °hm::;°] |

|

|

|

Figure #7 |

|

033 |

|

(1.9)#8 |

|

|

|

Figure #8 |

|

034

035 |

J

j l

l j |

ču, ču;+(0.5) °°.nh hf*::°°(0.6) no aby to bye bye (0.5) .nh hf:: (0.6)well so that >taps--+,,,tilts phone forward-> *...gaze J------> bylo °vtipný;°* (.)+°a blbý(h)° it would be funny (.) and silly(h) >gaze J-------*,,,,, +screenlock/phone away> |

|

036 |

L |

°he, [he;° |

|

037 |

J

j j |

[+.hFS+:::,:; +NO, [ .hFS:::,:; WELL >phone+...gaze L---+,,,gaze in front-> >----------+phone on sofa->> |

|

038 |

|

(0.3) |

|

039 |

L |

°hah::;°#9 hele prosím tě; °hah::;° hey listen |

|

|

|

Figure #9 |

|

040 |

J |

co je;=H:: what’s up=H:: |

|

041 |

L |

táta bude mít (.) svátek. it will be dad’s (.) name day. |

While simultaneously answering her mother’s topic-expanding question (002–004), Jitka visibly engages in another action trajectory: She begins to look at the table (Figure 1, 006), dissolves her sitting posture (007), bends forward and picks up the phone that has been lying on the coffee table in front of her (Figure 2). Jitka’s orientation towards the phone takes place in passing; she looks back at Ludmila while resuming her position on the sofa (Figure 3, 009), projecting the possible completeness of her answer. During the following reformulation of the answer (011, due to Ludmila’s lack of uptake, 010), Jitka keeps the phone in her hands and brings the screen into a ready-to-use position (Figure 4). Immediately after Ludmila’s minimal closing acknowledgement (012), Jitka initiates a new turn and sequence in which she announces that she has to contact a friend (013–015). The misplacement marker “hele” / ‘listen’ (013) indexes the upcoming turn as being unrelated to the directly prior talk (Schegloff/Sacks 1973). Visibly orienting her gaze towards the phone on her lap (Figure 5), and simultaneously unlocking and touching the screen, Jitka refers to the projected activity of writing a text message as something that had been planned in the past and that has already been delayed (‘I’ve realised that I haven’t written’), that is addressed to a specific person (the use of the proper name, indicating that Ludmila is expected to know this person), and that she is obliged to do (‘I will have to’). Finally, she announces a minimal suspension, as the SMS will be ‘quick’ (015). Despite these details, Ludmila pursues a further account (‘why’, 016), which Jitka promptly delivers (017[4]). Although Ludmila briefly stops looking at Jitka (end 017), she continues with a directive (‘so (.) write her an SMS’, 019), the use of the imperative displaying her high entitlement (Craven/Potter 2010). Once more, Jitka underlines the “quickness” of her projected texting (020), thereby acknowledging her mother’s entitlement.

While Jitka has been prepared to write the text message from very early on (anticipating the end of a topic and sequence, picking up her phone and bringing it into position), it is only after her mother’s directive (019) that she lifts the device and brings it into a writing position (Figure 6). This illustrates that she treats Ludmila’s directive as a type of go-ahead response to her announcement in first position[5]; thus, both turns form an announcement sequence. Jitka now begins tapping on the keyboard while simultaneously voicing the text (023–024). In the absence of screen capture, it cannot be confirmed that the voicing of the text corresponds to its precise input time on the screen; in any event, it addresses two practical problems (see DiDomenico et al. 2018; Suderland 2020). On the one hand, it makes the otherwise invisible text production on screen and its timing comprehensible for Ludmila (see Mortensen 2013: 122–124). On the other hand, it allows Jitka to continue interacting with her while proceeding to write the SMS. This is also shown by Ludmila responding to this voicing, specifically by assessing her daughter’s choice of address terms used in the text message (026, 028). In this way, the on-going writing/voicing activity surrounding the mobile device becomes intertwined with a sequence of talk between the co-present parties. However, Jitka’s minimal answer (029) shows that she does not project an expansion of this sequence at this moment, particularly as her gaze continues to be directed at the phone display.

Ludmila aligns with Jitka’s projected solitary activity by withdrawing her gaze at the end of the sequence (029, Figure 7), while Jitka continues voicing her text messaging activity (031). Ludmila now displays a posture of disengagement by not self-selecting for a next turn (033) and looking down (probably at her watch, Figure 8). Jitka’s greeting projects the end of her writing (034); directly afterwards, she stops tapping on the display and tilts the phone slightly forward, probably sending the text message. Only now does she provide a more elaborate response to Ludmila’s previous question regarding the use of the address term ‘babe’ (034–035; see 028). It is interesting that this bi-partite response (first a minimal response token at 029, then, after a gap, a full response, 034–035) is similar to the way in which she has answered previously (006, 008). Providing a quick, albeit minimal response (without looking at the co-participant) and then developing it at a later point (while looking back at the co-participant) allows Jitka to insert actions related to the device manipulation (007, 030–033) and to handle both involvements simultaneously. Consequently, this type of multiactivity is organised in a sequential rather than in a strictly simultaneous way (Mondada 2014). During her extended response to Ludmila, Jitka locks the screen and puts her phone to her right on the sofa (see Figure 9). Via a loud inbreath, a “no” (‘well’, 037) and looking back at Ludmila, Jitka audibly and visibly closes the device-related activity. Shortly afterwards, Ludmila initiates a new sequence and topic (039–041).

This first excerpt shows that the participants orient towards the accountable and potentially opaque character of device use in co-presence. It is interesting to note that, for Ludmila, Jitka’s account of having forgotten to write a message is not sufficient, and that she holds Jitka accountable for publicly providing another reason (016). Jitka’s further account – that she could not keep her promise to call, 017 – is acknowledged rather than being accepted by Ludmila (012). In fact, the rest of Ludmila’s third-position turn (019) displays her entitlement to permit Jitka’s device use,[6] and even to formulate a suggestion about the content of the message (021). In this sense, the device use has been framed by Ludmila as something that unnecessarily suspends the on-going interaction, to which Jitka’s voicing of the writing is a response that makes the suspending activity maximally public for Ludmila.

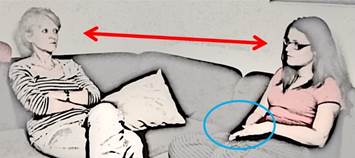

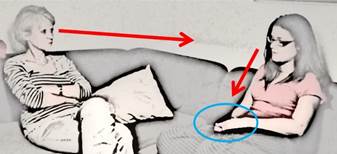

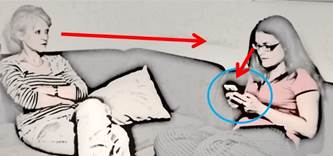

3.2 Writing a text message in a multi-party setting

In a dyadic setting – such as in the first excerpt – the device-use initiating participant is more likely to be held accountable for partially disengaging from the current conversation (see DiDomenico et al. 2018). In settings in which more than one participant can be addressed as a recipient or self-select as the next speaker, and in which schisms can lead to parallel conversations (Egbert 1993), the accountability of visible device use and the formulation of explicit accounts might consequently be reduced. Instead of being based on a purely numeric criterion (that is, two versus more participants), the second excerpt illustrates that the accountable nature of mobile device use in multi-party settings actually depends on the co-participants’ monitoring.

Four participants, Pavel (P), Anton (A), Milan (M) and Karel (K), are having some drinks on the terrace of a café following a joint soccer match of their amateur team (Figure 1). At the beginning of the excerpt, Pavel and Karel are not involved in the talk, while Anton and Milan are engaged in an on-going discussion of Milan’s work. Anton wonders about Milan’s handling of business-related documents when working on different computers (002–005). Anton is looking at his addressed recipient Milan, while Pavel and Karel both gaze in other directions and display no specific orientation towards any co-participant (Figure 1). This “by-sitter” status is used by Karel as an opportunity to take out his mobile phone and prepare to write a text message. In the course of the excerpt, Pavel’s visible orientation to Karel will lead to an announcement and thus an account of Karel’s device use.

Transcript (2): HAM_SMS_002150

|

001 |

|

(2.0)#1 |

|

Figure #1 |

||

|

002

003 |

A

k p

|

*.ts no právě proto mě za+ráží že prostě .ts yes exactly I am surprised that indeed *...gaze toward A----------------->006 >gaze down---------------+..lifts head +* materiály #2 [nějáké+připravu-]& the material [somehow prepare-]& |

|

004 |

P p p k |

[.h hf: ] +...gaze toward K------------->012 +lifts glass-> *...right Hand twd right pocket--> |

|

Figure #2 |

||

|

005 |

A |

&se [ připra*ví] &is [ prepared] |

|

006

007 |

M

k k

k |

[ale tak* tod- to-] todle jako#3*nevadí. [but so it- it-] this like doesn’t matter >twd A------*...gaze twd P---------------> left hand to left pocket*....> jo, (.)* °to- to- to-° todle prostě& right, (.) °it- it- it-° this simply& >gaze P---*,,, |

|

Figure #3 |

||

|

008 |

M |

&[myslím (se) jako (.) z pozice& &[I think (it) like (.) from the business& |

|

009 |

K

k p |

[*°bych° moh+ napsat Lukášovi;&& [ I could write to Lukáš && *..gaze twd P-----------------> >drinks------+,puts glass on table, touches> |

|

010 |

M |

&věci jako nevadilo,] &point of view it like doesn’t matter] |

|

011 |

K |

&&(se zeptám) jak to ] je, no; &&(I will ask) what about] it huh |

|

012 |

k |

*(0.2) *..takes phone out of pocket-> |

|

013 |

A |

+jako*+ne#4ni +to[*+jakoby:;+] like it isn’t [sort of ] |

|

014 |

P |

[°xx° ] |

|

015 |

K

|

[*+Lukášovi+#5][napíš]u:; [ to Lukáš][I will wr]ite |

|

016 |

M

p p k k |

[ne. ] [no ] +lifts head/chin+SPK+..gaze down t/his SP->> >glass+rHand,,,,,,,,+.......+touches his SP> >P----*,,gaze twd his mobile phone-------->> >-------------------*.takes phone in rHand-> |

|

Figure #4

Figure #5 |

||

|

017 |

M

p |

+ne ne ne; no no no +grabs his SP with rHand, repositions it> |

|

018 |

P |

a jako s (.) čim, [že a- e- ] and like with (.) what [that a- e-] |

|

019

020 |

K

|

[že jsme vy]hráli a že; [that we’ve] won and that +*(0.2) [ať přijde. ] (0.2) [he should come] |

|

021 |

P

p k |

[.ts (.) a ať] příde=m:#6(.)*příště, [.ts(.) and that he should] come_m:(.) next time +...left Hand to SP, uses both hands----->> *..retracts phone twd himself------*u/table> |

|

Figure #6 |

||

|

022 |

K |

on příde v [sobotu:;] he will come on [Saturday] |

|

023

024

025 |

A |

[stejně mě to ja]ko [anyway it li]ke překvapuje jo, protože vem si, surprises me right because for example (1.0) děláš to třeba v ňákym počítači:,& (1.0) you do that perhaps on some computer& |

Before reaching into his pocket for his mobile phone, Karel gazes in Anton’s direction, thereby monitoring the current speaker’s gaze orientation (002). As Anton is still and constantly looking at Milan, his turn (002–003, 005) can be understood as being addressed to Milan rather than to the others. While still monitoring Anton (see Figure 2), Karel begins searching the right pocket of his jacket with his right hand (003–004). At this point, Pavel looks up and at Karel (003, Figure 2). At the end of Anton’s turn, Karel redirects his gaze to Pavel (005–006, Figure 3). When both finally engage in mutual gaze, Pavel has already reached for his glass and is drinking (see Figure 3): Pavel monitors Karel, but does not project a turn at this moment (see also Goodwin 1981).

Shortly afterwards, Karel reaches into the left pocket of his jacket with his left hand, then initiates a turn in which he announces that he ‘could write to Lukáš’ (009, 011). His continuous gaze at Pavel and the turn-final tag (“no”, 011) make a response from Pavel relevant. Precisely after the end of this turn (012), Karel starts taking his mobile phone out of his pocket. However, at the end of the turn that he addresses to Pavel, Karel’s mobile phone is not yet visible (see Figure 3). In fact, while Pavel has constantly looked at Karel, he does not visibly respond and maintains a steady posture, indicating possible trouble concerning Karel’s announcement (Oloff 2018a). After the end of Karel’s turn (012–013), Pavel lifts his chin and simultaneously starts frowning (see Figure 4). This display of repair initiation is quickly dissolved, as he glances briefly at Karel’s now visible mobile phone (“SPK” in the multimodal annotation), then directs his gaze down to his own mobile device that is lying on the table (013–016, Figure 5). This change in trajectory is also visible in the movement of his right hand. During repair initiation, Pavel’s right hand is still touching the glass of beer he has just put down on the table (see Figure 4), but he then retracts his hand by lifting his forearm and, once he has seen Karel’s phone, he redirects his right hand to his own smartphone and unlocks the screen (Figure 5). It is difficult to say whether Pavel turns to his own smartphone because he has interpreted Karel’s turn as a possible request to write a (joint) message to Lukáš, or if he simply seizes Karel’s phone use as an opportunity to turn to and use his own mobile device. In either event, both Pavel and Karel reorient their gaze towards their respective mobile devices until the end of the excerpt (starting at 013, see Figures 5 and 6).

Karel’s reformulation (015) of his initial turn (009) pursues uptake of his announcement (Terasaki 2004) and orients towards the absence of Pavel’s response (the now turn-initial position of the proper name “Lukáš” in 015 indicating Karel’s orientation towards a possible repairable). Despite the absence of mutual gaze, both participants continue the sequence of talk initiated by Karel’s first announcement. As Karel has now announced for a second time that he will write a message to Lukáš, Pavel’s smartphone use does not seem to be related to the writing of a message to Lukáš, but rather to the checking and then writing of another message (see the later horizontal repositioning of his smartphone, 017). In his next question, Pavel asks about the possible content of Karel’s message (018). At the first possible transition-relevance place (Sacks et al. 1974), Karel responds by extending his previous turn with a relative clause (019), stating that he will tell Lukáš about their team’s victory and that he should come to the next match. With a retraction to the “a že” / ‘and that’, Pavel formulates a pre-emptive completion of Karel’s turn in overlap (020–021), responding in the absence of mutual gaze to the possible break in turn progressivity (Oloff 2018b; see Figure 6). The slightly rising final intonation on the last item in Pavel’s turn leads to a try-marked format (Sacks/Schegloff 1979: 16). Karel responds with a reformulated version (022), thereby treating Pavel’s turn as a request for confirmation and closing the sequence he had initiated in 009. Both Karel and Pavel now handle their respective mobile devices in silence, Karel being busy positioning his phone under the table in order to avoid light reflection (as he states 27 seconds later, not shown). Milan and Anton continue discussing the topic of Milan’s work and do not orient towards their co-participants’ mobile device use.

This excerpt illustrates that mobile device use in co-presence is not accountable a priori, and can be initiated or at least prepared without commenting on it, as Karel does when beginning to search for his phone in his pockets. However, the phone use becomes accountable as soon as the device user (here, Karel) perceives that he is being monitored by a co-participant (here, Pavel), which is mainly accomplished via gaze in face-to-face encounters (Goodwin, C. 1980; Goodwin M. H. 1980). In fact, Karel initiates the first announcement of his phone use soon after having established mutual gaze with Pavel. The fact that Karel pursues a response with a second, reformulated announcement shows that a response from the monitoring co-participant is expected. These announcements of mobile phone use therefore act as first pair parts within an announcement sequence, while the co-participant’s response in the second position provides a go-ahead for the device use (here, Pavel’s try-marked completion). If this go-ahead is minimal or dispreferred, as in Excerpt 1, the device use will be further accounted for (expanding the announcement sequence) and/or commented on (for example, by simultaneously voicing the actual writing process; see Excerpt 1).

The announcement itself seems to follow a specific structure. It first contains a description of the activity to come, namely that message writing will take place and, in both cases, the name of the addressee is offered as a recognitional reference (Schegloff 1996). This type of announcement also contains elements that are more clearly related to the accountability of the device use, which are upgraded in Excerpt 1 (stating the participant’s obligation to write the SMS), but which are unsurprisingly less strong in Excerpt 2, in which Karel is initially somewhat vague about the content of the message (011). The voicing of the text message, that is making the visible activity of writing audible, which only occurs in Excerpt 1, can thus be understood as a response to a co-participant’s request to deliver an upgraded account for the device use.

3.3 Making a phone call in co-presence

The announced, perceived and negotiated impact of mobile device use in a face-to-face encounter also depends on the type of use that is made of the mobile device. Writing a text message can be carried out silently (but implies gaze withdrawal), while making a phone call potentially competes with current talk (see Schmitt 2005) even if, in theory, mutual gaze with co-participants could be maintained during a phone call. The next excerpt illustrates this problematic potential of phone calls in the co-presence of others, and how recipients may respond to the absence of an announcement sequence.

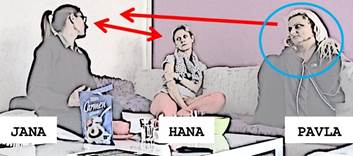

In Excerpt 3, Jana (J), Hana (H) and Pavla (P) are meeting at Pavla’s home. As Jana is no longer living in the same town, the three friends provide for thorough mutual updates during this meeting. At this point, Jana talks about the impossibility of selling her parents’ house and the importance of keeping them in their home environment for as long as possible. While Hana audibly and visibly displays her alignment and affiliation with Jana’s telling, Pavla has withdrawn from contributing actively to the on-going conversation because the (relatively silent) vibrate alert of her phone had gone off (18 seconds before the transcript began). Pavla has picked up her phone that was lying to her left on the couch, but keeps the phone in both hands as it only rang/vibrated twice. She has now decided to return the call and puts the phone to her ear (003, see Figure 1). During the call, she remains seated next to her friends, who gradually suspend their talk and respond to Pavla’s unannounced smartphone use in various ways.

Transcript (3): Pink_12_Phonecall Radek_002638

|

001

002 |

J

|

aby:::; na staré kolena °jako (vyžit so that at their time of life °like (enjoy [a jako) neztratili xx& [and like) that they don’t lose xx& |

|

003 |

H

p p |

[jasně, +někde- ano=ano=ano=+ano;&& [of course; somewhere- yes=yes=yes=yes&& +taps display, phone to ear--> >>gaze SP------------------------+.gaze J> |

|

004 |

J |

&jenom v příp][adě;° ] &just in cas][e ] |

|

005 |

H |

&&°mhm_hm ][mhm_hm°] |

|

006 |

P |

[mhm_hm,]#1(.) mhm_hm, |

|

Figure #1 |

||

|

007 |

|

(.) |

|

008 |

H |

°jas[ně.° °of [course° |

|

009

010 |

J

|

[.h:: (.) takže::; m: (0.8) to mi bylo [.h:: (.) so:: m: (0.8) for me it was (.) vždycky jako důležité; [a jako ten ]& (.)always like important [and like this]& |

|

011 |

H |

[mhm;_hm, ] |

|

012

013 |

J |

&barák je; (.) pro moje rodiče &house is (.) for my parents it znamená všechno; means everything |

|

014 |

|

(0.7) |

|

015

016 |

H |

°tak jasně,° (.) °yes of course° (.) [°celý život [tady žijou.°] [their whole lives [they’ve been living here] |

|

017 |

J

p |

[.h:: [takže:]+:;_m. [.h:: [ so:]:_m >gaze J------------------+gaze front/side> |

|

018 |

|

(0.4) |

|

019 |

P |

no a[hoj,] yes he[llo ] |

|

020 |

J |

[ jo:]:- (0.4) °mh::°#2(j)ako:_m. [yeah]: (0.4) °mh::° like:_m. |

|

Figure #2 |

||

|

021 |

P |

co si [chtěl Rad+ku; ] what did [you want Radek ] |

|

022

023 |

J

p |

[je to takhle, ] otevřené, [it is like that] open >gaze front/side---+...gaze J--> [a u]vidíme,+ co bu[de;] [and we]’ll see what will [be] |

|

024 |

H |

[mhm:_hm,] [jo= ]jo=[jo=jo. ] [mhm:_hm,] [yes=]yes[=yes=yes] |

|

025

026 |

P

p

j |

[ty si ] mi [but you‘]ve >gaze J-----+,,,gaze front/side-> %VOlal ale teďka- called me just now %..head/gaze to P->l.036 |

|

027 |

h |

*(0.4)*#3/3a(2.4---------)*(0.7) *..turns head quickly to P*,,gaze ahead-> *‘disapproval‘ face-* |

|

Figure #3 Figure #3a |

||

|

028 |

H |

hf:; |

|

029 |

h |

*(0.3)* *slight headshake* |

|

030

031

|

P

h

h |

ehe_he, ty si mi teďka *VOlal; (0.7) ehe_he, you’ve just now called me (0.7) >gaze ahead------------*..down-------> d(h)obré;#4(0.5) *tak jo:- a*hoj; g(h)ood (0.5) okay then bye >gaze down-------*...gaze P-*,,down-> |

|

Figure #4 |

||

|

032 |

h p p |

(0.9)*+(4.0)+(0.7) >down*..gaze P/head twd P--------> +..lowers SP, held in front-> +...gaze J, headshake, smile-> |

|

033 |

P |

#5°hF:° °.h° |

|

Figure #5 |

||

|

034 |

j p |

%(0.9) +(1.0) %light headshake, smiles >gaze J+,,,,gaze down/SP-> |

|

035 |

P |

.h::::, HF::::;#6 |

|

Figure #6 |

||

|

036 |

j |

(3.6) %(1.0) >twd P%,,,gaze forward-> |

|

037 |

P |

.h:: |

|

038 |

|

(3.8) |

|

039 |

P

P j h |

+no %mluv*te; nějak #7+jste potichu well talk you’re kind of silent +..gaze J--------------+..H----> %..gaze P------------------> *..gaze P-------------> |

|

Figure #7 |

||

|

040 |

H |

nHE: t(h)ak(h)= w(H)ell s(h)o= |

|

041 |

J |

=H::: [he;_he, he_he; .h::;]’ |

|

042

043 |

H |

[<:-)jsme tě nechtěly rušit [<:-)we didn’t want to disturb you u toho ne ne u:;>]’ while doing huh huh while:>] |

|

044 |

J |

[he_he- (.) .h: ] |

|

045

046 |

P |

[<:-)ne on mi volal omy]lem; Radek;> [no he called me by mis]take Radek [víš to já jsem ] se ze- co zas je,° [y‘know there I‘m ] with ze- what’s up now |

|

047 |

J |

[aha; ] |

|

048 |

|

(1.3) |

|

049 |

J |

kdo Radek- to je which Radek- this is |

While Jana is explaining why her parents should be able to stay in their house for as long as possible, Hana accompanies this formulation work by affiliative response tokens in overlap (001–005). Her close monitoring of Jana’s turn development (see also their mutual gaze, Figure 1) leads to an additional acknowledgement token at the next transition-relevance place (004–005). Pavla, who has initiated the call on the smartphone in the meantime and has put the phone to her ear (003), attempts to align with the on-going conversation by looking back at Jana (end of 003, see Figure 1) and formulating an acknowledgement (006), although it is late compared to Hana’s response and does not address Jana’s turn in a particularly affiliative way (compare Hana’s next turn at 008). Jana then elaborates on her prior explanations (009–013), which again is received by Hana with an upgraded affiliative response (015–016). While Jana self-selects again in overlap (017), Pavla withdraws her gaze (see Figure 2), probably because the person she has called is now responding to the summons, as shown by her subsequent greeting (‘yes hello’, 019, typically with no self-identification; see Arminen/Leinonen 2006).

As topic attrition and possible sequence closing has already been foreshadowed by Jana’s prior restarts and reformulations, it is impossible to say whether her turn suspension (020) is also linked to the fact that Pavla has now begun her phone call. At this point, however, Jana and Hana maintain their visible mutual engagement (Figure 2), and Jana’s continuation (022–023, projecting a closing more clearly; note the figure of speech she uses: ‘and we’ll see what will be’, Drew/Holt 1998) shows that, for the time being, Pavla’s simultaneous phone call (021) is not specifically receiving attention.

However, Pavla’s next turn in the phone call (025–026) occurs at a moment at which the next recipient response is due (see Hana’s multiple response tokens, 024). Although Pavla has continued to monitor Jana while being on the phone (see her gaze at Jana, 022–023), she now fully engages in the call, also displayed by the higher volume of her voice, probably related to the on-going repair sequence in the talk (see also her modified repeat in 030). During this turn, the dyad formed by Jana and Hana dissolves their mutual engagement and visibly attends to Pavla’s activity: Jana turns her head and gazes in Pavla’s direction; a moment later – and timed precisely with the end of Pavla’s turn – Hana quickly turns her head and also starts to look at Pavla (026–027, Figure 3). Both Hana and Jana have stopped talking and are now visibly and audibly attending to the phone call. Hana’s reorientation clearly implies a negative assessment of Pavla’s phone call activity: The speed of her gaze reorientation and the straightening of her posture, particularly of her neck, display some “surprise” (albeit well-timed with the transitionrelevance place in 026), and she adopts a facial expression that displays a negative, “disapproving” stance (pulled down corners of the mouth, raised eyebrows, widely opened eyes, held for nearly 2,5 seconds; see Figure 3a, a detail of Figure 3). Hana then turns her head back to a more relaxed position (end of 027), sighs audibly (028) and shakes her head slightly (029), thereby expanding her assessment.

Jana does not respond to Hana’s assessment, but looks in Pavla’s direction steadily while maintaining her posture (until 036). This frozen posture also has some assessment potential; in any event, this augmented monitoring – and not turning back to her prior interlockutor, Hana – displays a specific way of waiting (Figure 4). For her part, Hana exhibits a different way of “doing waiting”, as she now begins to look down and adopts a waiting posture (Figure 4). The fact that she glances quickly at Pavla, first when the closing of the call is projected (031), then after the end of the call (032, see Figure 5), shows that she is nevertheless monitoring Pavla’s activity and is not preparing to self-select for a next turn herself.

Pavla does not seem to have perceived her co-participants’ displays regarding her phone call, as she now simply lowers her phone, begins to look at Jana and assesses her phone call (or rather, the person she had called and the fact that he had previously called her inadvertently) with a headshake, a smile and a sigh (032–033, Figure 5). Although neither Jana nor Hana explicitly formulate or re-initiate their negative assessment, they remain visibly and audibly passive. Jana delivers a minimal and somewhat mechanical answer, responding to Pavla’s previous display with just a hint of a smile and a light headshake (034). Pavla does not respond to this lack of uptake, as she is still focused on the call’s aftermath; she looks back at her phone and sighs again (034–035, Figure 6; also note her facial expression). She continues to look at her phone for more than nine seconds (034–038), while Jana and Hana remain silent and do not look at Pavla (that is, they no longer look at her, as Jana also withdraws her gaze in 036).

After more than nine seconds, Pavla finally looks up, first at Jana, then at Hana, and initiates a new turn in which she requests her co-participants to talk (039, ‘well talk you’re kind of silent’). It is interesting that this turn neither initiates a new topic (for example, the content of the phone call), nor relates to the previous topic (Jana’s parents and their house), but points to a precise trouble source; that is, the co-participants’ noticeable absence of talk. With this explicit formulation, Pavla displays her understanding of the silence possibly being linked to her previous phone call activity; however, she does not provide an account or take responsibility for this silence (see also her smiling face in Figure 7). Both Hana and Jana quickly reorient their gaze to Pavla during this turn (039, Figure 7), and respond immediately afterwards: Jana with laughter (041, 044), and Hana with a more explicit account (042–043), framed as ironic by the initial laughter particles, possible disagreement markers (‘well so’, 040), and a smiling tone of voice.

It is only at this moment that Pavla seemingly accounts for her phone call, stating that her friend Radek previously called her ‘by mistake’ (045). It should be noted that Pavla does not account for her choice to call him back immediately, thus again minimising her responsibility for the reason and timing of her self-initiated phone call. Consequently, this account is not really acknowledged by her co-participants; Hana does not respond, while Jana simply produces a change-of-state token (047). Thus, no explicit acceptance of Pavla’s account is produced. Instead, the dispreferred tone of the exchange is retained as, after a considerable lapse (048) – and late with regard to the trouble source, the proper noun “Radek” – Jana initiates repair concerning this person reference (049), which again pushes back the acceptance of Pavla’s account. The participants then continue to talk about Radek and do not return to the phone call itself.

This excerpt shows how the participants visibly and audibly negotiate the situated (un)acceptability and moral implications (see Robles et al. 2018) of mobile device use in co-presence. Putting the phone to one’s ear and initiating a phone call by dialling and greeting the person called are not initially treated as problematic by the co-present others: Hana and Jana continue to discuss the previous topic and maintain a mutual orientation, treating Pavla’s phone call as an acceptable parallel engagement (although, as in the case of parallel conversations, there may be some possible perturbations in turn constructions, 020, 022, see Egbert 1993). The more and the longer the use of the device implies talk, the more Hana and Jana treat it as a disturbing parallel engagement. However, the “disturbance” is only visibly attended to and assessed as such after the prior sequence has been brought to a close (see Jana’s closing figure of speech). This sensitivity to transition-relevance places shows that Jana’s and Hana’s visible reorientation and possible “surprise” are staged rather than displaying actual changes in their cognitive states. Instead of treating the phone call verbally and explicitly as a complainable, both Hana and Jana practice a kind of “silent moralising”, thus restricting their assessment mainly to visible displays. Accordingly, they orient towards both a perturbation and Pavla’s responsibility for accounting for her mobile phone use, as both let the opportunity to take the turn after the end of the phone call pass, but continue to monitor Pavla.

While the initial simultaneity of talk and the phone call show that this is not problematic a priori (as participants in multi-party settings can and do routinely focus on on-going talk despite parallel conversations; see Egbert 1993), the marked suspension of the conversation in co-presence is clearly used to display an evaluative stance towards Pavla’s use of a mobile device. Jana and Hana orient towards the face-to-face conversation as the main and dominating involvement (see Goffman 1963: 43–59)[7]. However, while making her phone call, Pavla shifts her focus of attention away from the conversation, with the phone call becoming her individual dominating and main involvement, “[…] visibly forming the principal current determinant of h[er] actions” (Goffman 1963: 43). Through their responses, Jana and Hana reveal that they treat the conversation as the dominating involvement and expect Pavla to do so as well (as expressed via Hana’s ironic comment, 042–043, in which she pretends that the phone call was the dominating involvement for both herself and Jana, too). Of interest, Pavla’s co-participants do not immediately and explicitly assess the phone call itself as being problematic, but do so only after a comparatively long time once the phone call has ended; thus, several opportunities to deliver an account from Pavla’s side have already passed (032–039). Before Pavla’s complaint about her co-participants’ silence (039), she has not accounted for the call in any way; neither has she initiated an announcement sequence or a post-positioned apology, nor engaged in specific embodied conduct (such as turning away from the others or getting up from the sofa during the call). Thus, in this case, rather than treating the phone call as being problematic in this context, the participants might orient towards the absence of a routine announcement (or other type of account) of the mobile device use from Pavla’s side, which could have publicly and pre-emptively framed her disengagement from the on-going focused encounter. Based on this case alone, it cannot be claimed that the co-participants systematically orient towards the absence of an account rather than to the particular type of mobile device use (here, a phone call)[8]. However, this excerpt, as do the previous ones, illustrates that mobile device use within a focused encounter is treated as an accountable action, and that early positioned accounts (such as within an initial announcement) seem to be preferred to retrospective accounts.

4 Results and discussion

The analysis illustrated three cases of self-initiated mobile device use in everyday interactions in Czech. As the device uses were not related to prior or on-going talk, one might expect these uses to have led to a considerable disruption of the face-to-face encounter. However, the participants managed this solitary device use in various ways. The participants did not orient systematically towards mobile device use as a problem, and they only related to it explicitly as a problem of accountability (invoking possible social norms) in specific cases. The analysis of the three excerpts aimed to illustrate a major point: In contrast to that which could be expected intuittively, specific types of uses or specific participant constellations do not automatically define a specific degree of “social problematicity” of the mobile device use. Instead, the participants assess and manage the solitary device use with regard to different situated relevancies, which allows us to formulate some preferences and overall tendencies (see the introduction to Section 3):

• The channel or “technology” used (call/SMS/internet, audible/visible): If the device use requires the user’s full visual orientation, users are more likely to frame it verbally, while a phone call during an on-going conversation seems to be treated as requiring more of an account than writing a text message, for example.

• The topical and sequential fittedness of the device use with regard to the on-going talk: Participants tend to orient towards sequence endings and transition-relevant places for self-initiating their device use, and check beforehand whether they are possibly addressed recipients or not.

• The participant constellation (dyadic/multi-party) and specific membership categories: While device users in dyadic settings might orient towards a stronger accountability of their device-related activity and seem to be more inclined to announce and comment on it, in multi-party settings, framing the device use is carried out when users perceive that they are being monitored. The form of the accounting (extended, Extract 1, or somewhat short, Extract 2) is possibly also related to specific membership categories and (a)symmetries.

• The opacity of what is done with the device: In general, participants treat the display as opaque for co-participants and their actions on screen as somehow accountable, unless the device use is visibly and/or audibly clear, as in the case of a phone call.

• The possible opacity of how the device use is multimodally framed by its user: In the absence of explicit or clear announcements by the user, co-participants engage in prolonged monitoring activities in order to evaluate how the device use is related and relevant to the previous and on-going activity. If they treat the announcement as insufficient or noticeably absent, they can pursue extended accounts from the user and can even engage in “everyday moralising”.

This shows that the framing of mobile device use in the co-presence of others is related to the management of recurrent practical issues in social interaction. It is based on the co-participants’ joint negotiation of their mutual availability, and how they jointly treat and acknowledge the public recognisability and sequential implicativeness of the device-related actions for the on-going encounter, rather than simply being an issue of individuals’ face work or of generally steady, external moral or politeness standards that are applied consistently and automatically. A systematic practice that is available to participants for managing independent device use is the announcement sequence, in which a first pair part formulated by the device user serves to announce the type of activity – and thus the possible suspension of further (joint) talk – and a second pair part by a co-participant that acknowledges the announcement and thus serves as go-ahead response. However, mobile device announcement sequences are not typical “announcements” as they have been formerly described in other settings: Unlike news delivery and informings, they do not seem to project an assessment as a next action (see Pomerantz 1984; Terasaki 2004), and do not provide an assessment or an evaluative stance in the first position (see also Keel 2011). Announcements of mobile device use remain somewhat factual regarding the projected activity, and do not display a specific evaluative stance. However, they seem to be more ambiguous with regard to the projected response. While a simple acknowledgement could be sufficient, recipients can also provide more elaborate responses that ask for more information about the motivations and content of the actions to be carried out via the mobile device (‘why’, Example 1, ‘with/about what’, Example 2). It is in these expansions that a possible evaluative stance can be displayed by the co-participant, and subsequently be responded to by the mobile device user. Thus, while a simple acknowledgement in the second position works as a go-ahead and immediately closes the announcement sequence, other types of responses can expand the sequence and possibly delay the announced device use. The recipient’s response (and possibly displayed stance) has implications for how the actual device use is then carried out – as a public, comprehensible and transparent activity (by concurrently glossing the on-going use, Example 1), or as a publicly announced, but solitary and private activity (Example 2).

It is usually – and unsurprisingly – the device user who is held responsible for providing an account for the device use. This is shown in Example 3, in which neither co-participant formulates verbally explicit pursuits of an account (for example, Jana’s absence of a verbal statement after Pavla has noticed the gap, and Hana referring to the silence as means of not disturbing Pavla’s call). As a result, both co-participants leave the recognition of being solely accountable to the device user, Pavla. The fact that the indirect pursuit of an account only occurs after a possible sequence closing – which up to this point had been developed simultaneously with the phone call – hints at the possibility that it might not be the phone call as such that is treated as problematic, but rather the absence of any announcement of the concurrent device use – and thus the absence of a structured and jointly negotiated withdrawal from the previously established participation framework.

While the announcement sequence appears to be a systematic practice for managing self-initiated phone use in the co-presence of others, its absence does not automatically imply that the mobile device use will be received negatively by the co-participants. However, the absence of an announcement sequence might lead to other practical problems, such as a lack of public recognisability of the boundaries between different communication involvements. The difference between the presence and absence of an announcement sequence cannot be discussed in this contribution. It is sufficient to say that, in both cases, the device use has a certain impact on the overall progressivity of the face-to-face interaction. Knowing whether participants have already developed other routine practices for specifically managing the double involvement of talk and mobile device use (such as the announcement sequence, and similar to certain professional multiactivity practices, Mondada 2014; see also Suderland 2020: 116–118) requires further examples and detailed multimodal investigations of the systematics of mobile device use in face-to-face interaction.

References

Arminen, Ilkka/Leinonen, Minna (2006): Mobile phone call openings: tailoring answers to personalized summonses. In: Discourse Studies 8 (3), 339–368.

Berker, Thomas (2006): Domestication of Media and Technology. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

Brown, Barry/McGregor, Moira/Laurier, Eric (2013): iPhone in vivo: Video Analysis of Mobile Device Use. In: CHI 2013: Changing Perspectives, Paris, 1031–1040.

Brown, Barry/McGregor, Moira/McMillan, Donald (2015): Searchable Objects: Search in Everyday Conversation. In: CWSW 2015, Vancouver, ACM Press, 508–517.

Craven, Alexandra/Potter, Jonathan (2010): Directives: Entitlement and contingency in action. In: Discourse Studies 12 (4), 419–442.

Cumiskey, Kathleen M. (2005): “Surprisingly, Nobody Tried to Caution Her”: Perceptions of Intentionality and the Role of Social Responsibility in the Public Use of Mobile Phones. In: Ling, Richard Seyler/Pedersen, Per E. (Eds.). Mobile Communications: Re-negotiation of the Social Sphere. London: Springer, 225–236.

de Souza e Silva, Adriana (2006): Interfaces of Hybrid Spaces. In: Kavoori, Anandam/Arceneaux, Noah (Eds.). The cell phone reader: essays in social transformation. New York: Peter Lang, 19–43.

Deppermann, Arnulf/Streeck, Jürgen (Eds.) (2018): Time in Embodied Interaction. Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

DiDomenico, Stephen M./Boase, Jeffrey (2013): Bringing mobiles into the conversation: Applying a conversation analytic approach to the study of mobiles in co-present interaction. In: Tannen, Deborah/Trester, Anna Marie (Eds.). Discourse 2.0: Language and new media. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 119–131.

DiDomenico, Stephen M./Raclaw, Joshua/Robles, Jessica S. (2018): Attending to the mobile text summons: Managing multiple communicative activities across co-present and technologically-mediated interpersonal interactions. In: Communication Research doi: 0093650218803537.

Drew, Paul/Holt, Elizabeth (1998): Figures of speech: Figurative expressions and the management of topic transition in conversation In: Language in Society 27(4), 495–522.

Du Gay, Paul/Hall, Stuart/Janes, Linda/Mackay, Hugh/Negus, Keith (1997): Doing cultural studies: the story of the Sony Walkman. London: Sage.

Egbert, Maria (1993). Schisming: The Transformation from a Single Conversation to Multiple Conversations. Doctoral Dissertation in Applied Linguistics. Los Angeles: UCLA.

Fischer, Claude S. (1992): America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Geser, Hans (2004): Towards a Sociological Theory of the Mobile Phone. In: Professor Hans Geser: Online Publications. Zurich, May 2004 (Release 3.0). http://geser.net/mobile/t_geser1.pdf

Geser, Hans (2005): Is the Cell Phone undermining the Social Order? Understanding Mobile technology in a Sociological Perspective. In: Glotz, Peter/Bertsch, Stefan/Locke, Chris (Eds.). Thumb culture. The meaning of mobile phones for society. Bielefeld: transcript, 23–35.

Goffman, Erving (1963): Behavior in Public Places. Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings. New York: The Free Press.

Goggin, Gerard (2006): Cell Phone Culture. Mobile technology in everyday life. London/New York: Routledge.

Goodwin, Charles (1980): Restarts, Pauses, and the Achievement of a State of Mutual Gaze at Turn-Beginning. In: Sociological Inquiry 50, 272–302.

Goodwin, Charles (1981): Conversational Organization. Interaction between Speakers and Hearers. New York: Academic Press.

Goodwin, Marjorie H. (1980): Processes of mutual monitoring implicated in the production of description sequences. In: Sociological Inquiry 50, 303–317.

Höflich, Joachim R. (1996): Technisch vermittelte interpersonale Kommunikation. Grundlagen, organisatorische Medienverwendung, Konstitution “elektronischer Gemeinschaften”. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Höflich, Joachim R. (2005): The mobile phone and the dynamic between private and public communication: Results of an international exploratory study. In: Glotz, Peter/Bertsch, Stefan/Locke, Chris (Eds.). Thumb culture. The meaning of mobile phones for society. Bielefeld: transcript, 123–135.

Höflich, Joachim R. (2009): Mobile Phone Calls and Emotional Stress. In: Vincent, Diane/Fortunati, Leopoldina (Eds.). Electronic emotion: the mediation of emotion via information and communication technologies. Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang, 63–83.

Höflich, Joachim R. (2014): Doing mobility. Menschen in Bewegung, Aktivitätsmuster, Zwischenräume und mobile Kommunikation. In: Wimmer, Jeffrey/Hartmann, Maren (Eds.). Medienkommunikation in Bewegung. Mobilisierung – Mobile Medien – Kommunikative Mobilität. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 31–45.

Höflich, Joachim R./Kircher, Georg F. (2010): Moving and lingering: the mobile phone in public space. In: Höflich, Joachim R./Kircher, Georg F./Linke, Christine/Schlote, Isabel (Eds.). Mobile media and the change of everyday life. Frankfurt, M.: Lang, 61–95.

Ictech, Brad (2019). Smartphones and Face-to-Face Interaction: Digital Cross-Talk during Encounters in Everyday Life. Symbolic Interaction, 42(1), 27–45. doi: 10.1002/symb.406

Jefferson, Gail (2004): Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In: Lerner, Gene H. (Ed.). Conversation Analysis. Studies from the first generation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 13–31.

Katz, James E. (2006): Magic in the air: mobile communication and the transformation of social life. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Katz, James E./Aakhus, Mark (eds.) (2002): Perpetual contact. Mobile communication, private talk, public performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keel, Sara (2011): The parents’ questioning repeats in response to young children’s evaluative turns. In: Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 12, 52–94.

Keppler, Angela (2019): “Zeig mal”: Smartphones im Gespräch. In: Marx, Konstanze/Schmidt, Axel (Eds.). Interaktion und Medien. Interaktionsanalytische Zugänge zu medienvermittelter Kommunikation. Heidelberg: Winter Verlag, 177–190.

König, Katharina/Oloff, Florence (2019): Mobile Medienpraktiken im Spannungsfeld von Öffentlichkeit, Privatheit und Anonymität. In: Journal für Medienlinguistik 2 (2), 1–27, https://doi.org/10.21248/jfml.2019.9.

Kopomaa, Timo (2000): The city in your pocket: birth of the mobile information society. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Lasén, Amparo (2005): Understanding mobile phone users and usage. Newbury: Vodafone Group R&D.

Lasén, Amparo (2006): How to be in two places at the same time? Mobile phone use in public places. In: Höflich, Joachim R./Hartmann, Maren (Eds.). Mobile communication in everyday life: ethnographic views, observations, and reflections. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 227–251.

Ling, Richard S. (1997): "One Can Talk about Common Manners!": The Use of Mobile Telephones in Inappropriate Situations. In: Haddon, Leslie (Ed.). Themes in mobile telephony Final Report of the COST 248 Home and Work group. Farsta: Telia.

Ling, Richard S. (2004): The Mobile Connection: The Cell Phone's Impact on Society. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann.

Ling, Richard S. (2008): New Tech, New Ties: How Mobile Communication Is Reshaping Social Cohesion. MIT: MIT Press.

Ling, Richard S./Yttri, Birgitte (1999): “Nobody sits at home and waits for the telephone to ring”: Micro and hyper-coordination through the use of the mobile telephone. Telenor Forskning og Utvikling, FoU Rapport, 1–27.

Mantere, Eerik/Raudaskoski, Sanna (2017): The sticky media device. In: Lahikainen, Anja Riita/Mälkiä, Tiina/Repo, Katja (Eds.). Media, Family Interaction and the Digitalization of Childhood. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 135–154.

Mondada, Lorenza (2013a): Multimodal interaction. In: Müller, Cornelia/Cienki, Alan/Fricke, Ellen/Ladewig, Silva/McNeill, David/Tessendorf, Sedinha (Eds.). Body – Language – Communication: An International Handbook on Multimodality in Human Interaction. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, 577–589.

Mondada, Lorenza (2013b): The Conversation Analytic Approach to Data Collection. In: Sidnell, Jack/Stivers, Tanya (Eds.). The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 32–56.

Mondada, Lorenza (2014): The temporal orders of multiactivity. Operating and demonstrating in the surgical theatre. In: Haddington, Pentti/Keisanen, Tiina/Mondada, Lorenza/Nevile, Maurice (Eds.). Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond multitasking. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 33–76.

Mondada, Lorenza (2016): Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. In: Journal of Sociolinguistics 20 (3), 336–366.

Mortensen, Kristian (2013): Writing Aloud: Some Interactional Functions of the Public Display of Emergent Writing. In: Melkas, Helinä/Buur, Jacob (Eds.). Proceedings of the Participatory Innovation Conference PIN-C 2013. Lahti: Lappeenranta University of Technology, 119–125.