Vol 4 (2021), No 2: 85–122

DOI: 10.21248/jfml.2021.31

Discussion paper available at:

Constructing co-presence through shared VR gameplay

Abstract

This study analyzes how participants playing VR games construct co-presence and shared gameplay. The analysis focuses on instances of play where one person is wearing the VR equipment, and other participants are located nearby without the ability to directly interact with the game. We first show how the active player using the VR equipment draws on talk and embodied activity to signal their presence in the shared physical environment, while simultaneously conducting actions in the virtual space, and thus creates spaces for the other participants to take part in gameplay. Second, we describe how other participants draw on the contextual configurations of the moment in displaying co-presence and position themselves as active and consequential co-players. The analysis demonstrates how gameplay can be communicatively constructed even in situations where the participants have differential rights and possibilities to act and influence the game.

Keywords: conversation, conversation analysis, co-presence, shared gameplay, single player games, VR-games

1 Introduction

This study analyzes how participants negotiate presence and coconstruct gameplay when playing single player virtual reality (VR) games together. Originally, approaches to understanding presence focused on ‘perceptual illusion of nonmediation’ being produced by certain factors, such as realism in the environment, and the degree of immersiveness created by the interface (Lombard/Ditton 1997). The focus in such cases has typically been on the individual’s psychological experience. Our analysis, in contrast, concentrates on the social aspect of presence and play – the observable practices through which participants create a sense of ‘being together’, or co-presence (Goffman 1966), in shared play-situations using VR equipment.

As a context, VR presents specific kinds of challenges for social play. Typically, the physical set-up of putting on a headset allows for one user to be immersed in the mediated environment, while leaving others without similar equipment into the role of the spectator. Yet, studies of gaming interaction show that ‘spectators’ should not be seen simply as passive observers, but that they engage in different forms of participation ranging from silent viewing to actively taking part in gameplay (e. g. Isbister 2010, Tekin/Reeves 2017, Baldauf/ Colón de Carvajal, this issue). With the help of a close inspection of recordings of instances of play, we analyze how participants who do not have similar access to the technological resources co-construct gameplay through a dynamic process of managing presence in virtual and physical spaces.

The data for this study come from instances of play where one person is in charge of the controllers and wearing the VR equipment, and other participants are located nearby – sitting or standing in the same room with a view into the game world through an external screen, but without the ability to directly interact with the game. The participants thus have differential rights and possibilities to act and influence the game. This asymmetry structures participation and influences the way in which the interaction is organised. Our analysis builds on an action-based approach to gaming as multimodal interaction in technosocial space (see e. g. Keating/Sunakawa 2010, 2011, Arminen/Koskela/Vaajala 2008). We also draw on Goodwin’s (2000, see also 2007, 2013) notion of contextual configuration as an entry point into understanding how co-presence is a ‘product’ of locally negotiated resources and material structures. Here, material structures refer to the way the VR technology shapes the organization of action and creates affordances for social interaction. The analysis focuses on the multimodal constitution of co-presence: how participants use multimodal resources to construct and make presence relevant to each other, and how this is consequential for the actions through which gameplay evolves.

We aim to show how shared gameplay is achieved through the participants’ orientations to the temporal unfolding of the game and their shifting alignments between the virtual and physical space. The player wearing the VR headset uses the tools, language and bodily resources to display presence and act within and across the virtual and physical space. The other participants are involved in interaction with the game through their actions achieved through talk and visible embodied displays. These actions contribute to the organization and sociability of the play event in a continuous movement between different orientations towards the game as well as the other participants.

2 Gameplay as interactional activity

In studying games and gameplay, especially within the context of single-player games, there exists a long tradition where researchers have analyzed games by playing them themselves, often utilizing some form of structuralist analysis (Mäyrä 2008). Another popular choice has been to observe and interview individual players in order to understand their subjective perceptions and experiences with game systems (Jørgensen 2012).

In contrast, studies anchored in an ethnomethodological or conversation analytic perspective on games investigate gaming as a practical accomplishment and draw attention to the sequentially and temporally organized activities that constitute gameplay (e. g. Bennerstedt 2013, Bennerstedt/Ivarsson 2010). This involves close analysis of naturally occurring gaming activities paying attention to the players’ engagements with technologies and the mechanics of gameplay as well as the methods of action through which social aspects of play are accomplished. The latter is what Isbister (2010: 12) calls ‘social play’: “active engagement with a game (through use of its controls or through observation and attention to ongoing game play) by more than one person at once.”

Studies looking at social play have focused on joint play activities in diverse material environments, such as the home (Mondada 2012, 2013, Piirainen-Marsh 2012) or spaces dedicated to gaming (e. g. LAN parties, internet cafes) (Keating/Sunakawa 2010, 2011, Sjöblom 2011). As Reeves et al. (2017) observe, one group of studies mainly focuses on the verbal and bodily actions by players around the game and pay attention to the game and on-screen activities as resources for talk, while others specifically investigate the organization of ingame actions as they become visible on the screen (e. g. Laurier/Reeves 2014). A number of studies show how video gaming activities involve different forms of participation and shifts from one type of activity to another (e. g. Keating/Sunakawa 2010, Mondada 2012, 2013), such that they can be characterized as multiactivity settings (Haddington et al. 2014, Reeves/Greiffenhagen/Laurier 2017).

The implications and effects of social play can be manifold. Earlier research has indicated that co-located play adds to the fun, challenge, as well as perceived competence in the game (Gajadhar/de Kort/IJsselstejn 2008). On the other hand, in some cases, the presence of other people is seen as a possible interruption or distraction to gameplay (Sweetser/Wyeth 2005). Social play may also tie in play as performance (Stenros/Paavilainen/Mäyrä 2009; Baldauf-Quilliatre/Colón de Carvajal 2015).

In addition to utilizing an ethnomethodological and conversation analytic perspective, we apply the lens of a recent theorization of gameplay by Larsen and Walther (Larsen/Walther 2019). Their conception draws on Heidegger’s notion of Dasein (1996 [1927]) and sees gameplay as coming about from the tension between play and game, and from their dimensions of being-here and being-there. This means that there is a temporal orientation to all gameplay, a kind of continuous dialectical tension – or, in Larsen and Walther’s words, oscillating dynamic – between freely playful and more structured modes of participation.

Larsen and Walther’s (2019) theory, or framework, contains multiple elements, and it is beyond the scope of this study to take it into account in its entirety. What we focus on here is the theory’s explanation of the oscillatory, dynamic level of gameplay. Understanding gameplay as dynamically oscillating highlights the need to approach it as a continuously evolving process. This approach also resonates with Goodwin’s (2000: 1517) viewpoint on how human action is constructed in a kind of a “temporally unfolding juxtaposition of multiple semiotic fields.” Where the original theorization focuses on the individual player’s experience, our contribution is in illustrating how multiple participants engaged in playing a single-player VR game jointly co-construct gameplay moment by moment by drawing on talk, bodily action and the semiotic and material resources of the environment. Consequently, we show how the co-construction of gameplay can be tied in with the construction of co-presence.

3 Method

3.1 Data collection

The data comprises video-recorded instances of VR gaming with multiple participants who were playing a number of different types of games. VR setups vary significantly in their complexity and style. As a general rule of thumb, a typical consumer-level VR equipment meant for gaming purposes includes some kind of a headset or visor for visuals, a system of loudspeakers or headphones for audio, and hand-held controllers for interacting with the game. While using a visor to block visual feed from the outside reality seems to make the experience more geared towards the individual, the systems are usually designed to allow for a video feed to be transmitted to an external screen. Some VR games even build on this affordance specifically, for example by having one player engage with the game via the headset, and the others seeing a different view presented on the external screen and interacting with the game that way.

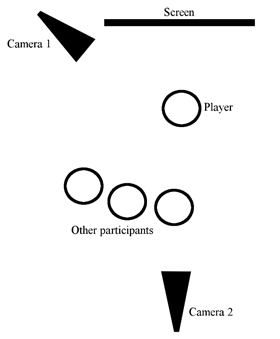

For this study, we built a temporary game lab with consumer-grade VR equipment available for the general public in 2018. More specifically, we used PlayStation VR. The setup of the game lab is illustrated in Figure 1. One person was in charge of the controllers and wearing the VR equipment. Other participants, as well as the researchers, were seated nearby the player. In addition to the VR equipment, a large screen displayed the video feed coming from the console – similar to a TV setup in a living room. We also used loudspeakers for the game sound, enabling everyone in the room to hear the soundscape of the game. We recorded the gaming situations with a setup involving three video feeds. One feed showed the screen and what was happening in the game. One feed came from a video camera pointed at the player, and another came from a video camera positioned behind the participants. This setup allowed for us to see both what was happening in the game, as well as in the room in general. We recorded both the game audio as well as the conversation between the participants.

Figure 1: The game lab setup

We collected data on four different occasions in the spring of 2018. Participants were university students with little or no experience in VR gaming. Each session lasted between 135–155 minutes and involved 3–4 participants, who took turns in controlling the game. Altogether ten students participated in the sessions.

3.2 Transcription

To enable systematic analysis of the changing dynamics of participation, we have created transcripts of the focal episodes following the principles of Jefferson’s transcription conventions and multimodal transcription developed in multimodal CA (Mondada 2014b, 2018).[1] The transcripts represent the multimodal conduct of the participants, i. e. the active player and the co-participants. The aim was to capture their (i) embodied activities and their relation to talk as well as (ii) the active player’s in-game actions that become visible on the large screen and are thus available for scrutiny by those participants who were not directly in control of the game. Images are used to show how multimodal actions and visual resources are timed relative to talk.

3.3 Data analysis

Our analysis builds on the ethnomethodological understanding of the participants’ talk and action as constituting an analysis of both the unfolding events and scenes in the virtual space and each other’s actions in the physical environment. The interactional organization of co-presence and sense of shared play is achieved through emergent courses of action by multiple participants who occupy different positions in the situation and use the resources available to them to contribute to the events.

The analysis traces the multimodal practices through which the participants display engagement with the game and build co-presence by using talk, bodily action, visual and material resources for action. The main interest is in moments where the sequential organization of talk and embodied activity are intertwined with the active player’s actions that become visible through the screen. We describe two extended cases drawn from the larger data set to illustrate how the game unfolds through a dynamic movement from single player orientation to team-orientation where multiple participants contribute to gameplay in a coordinated way. The cases illustrate the methods that the participants use to establish interactional opportunities for joint play. First, we show how the active player using the VR equipment draws on talk and embodied activity to signal their presence in the shared physical environment, while simultaneously conducting actions in the virtual space, and thus creates spaces for the other participants to take part in negotiating emerging puzzles of the game. Second, we describe how the other participants draw on the contextual configurations of the moment in displaying presence and position themselves as co-players whose contributions are consequential to unfolding gameplay.

4 Findings – the interactional organization of co-presence and gameplay

The examples to follow illustrate how the active player’s verbal commentary, coordinated with the use of embodied resources (virtual gaze, head pointing and body shifts), works to invoke and sustain co-presence and create opportunities for the other participants to align with the current play activity and move from ‘spectators’ to active members of a team engaged in gameplay. While the player using the controls has the primary right and responsibility for advancing gameplay, they orient to the others in the shared physical space, whom they cannot see, as co-participants in a multiparty participation framework where they can be recruited (Kendrick/Drew 2016) to assist in solving the puzzles of the game.

4.1 Case 1: Confusing contraption

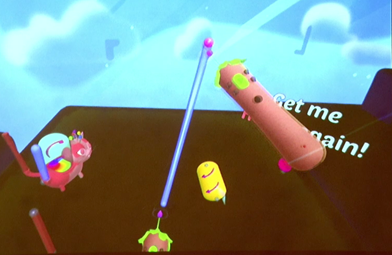

The first extended case shows how the participants establish and sustain co-presence while playing a VR construction game. The game, Fantastic Contraption (Radial Games 2017), places the player in a room with colorful materials (e. g. wheels, beams, sticks) that they can use to build machines (see Fig. 2). The active player uses two motion controls to pick up, move and manipulate the materials and tries to fit them together to construct a working machine, in this case a type of car that can drive itself across the virtual play area. The episode below begins when Simo has been working on the task for approximately 2 minutes. The others are monitoring his progress and show their alignment by means of occasional comments and embodied displays (e. g. shared laughter). Moments before the excerpt begins, Simo has succeeded in solving the task and now begins a new one. The analysis to follow details how the construction task unfolds temporally as a collective activity, where the multiparty participation framework is mobilized to assist in resolving puzzles that the game offers. At the start of the excerpt, Simo observes new materials that appear in front of him and starts picking them up, while also visually scanning the environment. This is visible to the others through his embodied conduct (head movements from left to right and small adjustments to his body position) and the way these are represented as changing views on the screen. Another participant, Matti, draws Simo’s attention to the new materials (lines 2-3), but Simo quickly establishes his primary rights to knowledge (epistemic primacy, Stivers/Mondada/Steensig 2011) (line 4) and launches the new activity with a noticing that displays his evolving understanding of the task (lines 4-6).

Figure 2: Screen view of Fantastic Contraption

Excerpt 1: Formulating understanding of the task

|

1

Simo ihan kohta |

|

2

Matti niin siitä kasvaa kato (.) |

|

3

jatkuvasti lisää ni[itä.] |

|

4

Simo [I kn]ow. |

|

5

*nyt mie huomaanki= |

|

6

oho *tonne pitää *lingota se. |

Figure 3: Virtual gaze and headpointing Figure 4: Head down

|

7

ja °nä*in tässä pyöreä.° |

|

8

(0.5) |

|

9

mitä nää *on (.) nuppineuloja.* |

|

10

Hannu *onko ne koristeita |

|

11

(3.0) ((gong

noise)) |

|

12

Simo *m[itäs ihmet*tä. |

Figure 5: Pointing with controller

|

13

Matti [nii::n#]= |

|

14

Simo *=pitäs päästä tonne ylös. mun

pitää niinkun |

|

15

*(2.0) |

Figure 6: Visible searching

Simo’s noticing (lines 4–6) displays presence in both the virtual space and the physical environment. A verbal meta-comment (‘now I notice’), followed by a change of state token (‘oho’) are finely coordinated with head movement, visible as a virtual gaze shift, which shows change of attentional focus to a specific part of the play area. These actions show the player’s simultaneous orientation to the here and now of the virtual space and the shared physical space, where the others are following his actions via the screen.

As the utterance continues, the emergent and forward-orienting nature of gameplay becomes evident when Simo produces a verbal formulation that projects the goal of the task. He refers to the direction of movement where the new car needs to move and uses a visible head point to index the deictic reference (‘that’s where’) (line 6, Fig. 3). The embodied formulation makes Simo’s reasoning available to the others through multiple semiotic fields: vocally, through visible bodily shifts, and through changing scenes on the external screen (see also Bennerstedt/Ivarsson 2010). Following this, Simo continues to scan the environment, picks up objects and provides on-line commentary on the items that are visible (lines 7–9). Simo’s verbal utterances in lines 6 and 7 indicate possible turn completion via syntactic and prosodic cues and thereby create occasions for the others to initiate talk. However, the other participants do not self-select; instead, they silently direct their attention to the screen and follow Simo’s virtual actions, which unfold continuously without a break. In line 9 Simo produces an interrogatively formulated turn (‘what are these (.) pins’, line 9), which is co-produced with the action of picking up a ‘pin’ and putting it down again. The turn is recognizable as a rhetorical question, as the interrogative TCU is followed by a candidate answer. It occasions an aligning response, a Y/N question suggesting an alternative candidate answer, from Hannu (line 10), but does not lead to further talk. Simo continues to manipulate the materials and the others observe this in silence (line 11). This suggests that identifying and naming the virtual objects is not a primary concern for the participants; rather they focus on the moves through which Simo advances the larger construction activity.

In line 12, Simo shifts his attention to the right side of the play area, which shows a large wall, an obstacle for the car that he is building. This new challenge occasions a display of surprise (‘what on earth’, line 12). Concurrently with the end of the verbal turn, Simo begins a virtual pointing gesture (Fig. 5) and then formulates his evolving understanding of the task ahead by referring to the direction where he needs to get the car to move (‘up there’, line 14). The verbal utterance is syntactically incomplete and followed by a visible search in the virtual space (Fig. 6), displayed by Simo’s embodied actions (head movements, changes on the screen showing changing direction of gaze). The search continues for 2.0 seconds during which the others watch the screen in silence. Unlike the verbal turns earlier, this moment of task trouble occasions offers of assistance from two other participants and enables them to team up with Simo in solving the problem.

Excerpt 2: Possible solution 1: assembly line

|

16

Hannu *siihen ¤pitäs tehdä |

|

17

semmoinen ¤liukuhihnahomma= |

|

18

Kari niin¤ mäkin (miet-) |

|

|

|

19

Simo liukuhihna*. ai

niinkun näistä semmon*en eh |

|

20

Kari (tää kestää vaan)

viiskytkaheksan (tuntia) |

|

21

Hannu #£nih£ |

The silence is broken by Hannu, who offers a possible solution (line 16-17) to the trouble and suggests that what is needed is a ‘kind of assembly line’, which would enable the machine to climb over the wall. Through its linguistic design – hedging and reusing resources from Simo’s turn (‘pitäs tehdä’ / should make, ‘semmonen’ / a kind of) – the utterance is designed as a helpful suggestion, which is sensitive to Simo’s observable efforts to find a way to proceed. The turn aligns with the forward orienting actions of the player and claims some degree of knowledge that is relevant to solving the problem. At the same time, it attends to the participants’ asymmetrical access to the controls as well as their social positioning by showing orientation to Simo’s primary right to make decisions about gameplay.

Hannu’s verbal characterization of the imagined object (‘assembly line thing’) is accompanied by a gesture, a linear movement of his right hand followed by a circling movement. The gesture depicts the imagined virtual object that is referred to in talk and traces the movement of the vehicle towards the wall on the righthand side of the play area. Depictive gestures typically convey interactional meaning to recipients in that they elaborate verbal TCUs and contribute to the recognizability of the actions that are being produced, especially if the gesture is extended beyond the end of the TCU (Streeck/Haartge 1992; Lilja/Piirainen-Marsh 2019). However, the contextual configuration restricts its visibility to the others, especially the player Simo. Nevertheless, the gesture displays Hannu’s close monitoring of the virtual space and contextualizes his suggestion. Hannu’s actions occasion an aligning comment from Kari, who is seated next to him (line 18). The suggestion is also quickly picked up by Simo. He repeats the key term and simultaneously stops manipulating the objects: he puts down a yellow cylinder that he had picked up and shifts his gaze from the objects towards the obstacle on the right (line 19). These actions indicate a change of orientation; Simo seems to be formulating a local understanding of what it might mean to follow the suggestion. At this point the other two participants momentarily withdraw from engagement with the game and align with each other. Kari makes an ironic comment referring to the time it takes to solve the problem and Hannu agrees with a smile (lines 20–21). Next, Kari offers another suggestion, building a ramp (lines 22–23):

Excerpt 3: Possible solution 2: building a ramp

|

22

Kari *tai ^mä mietin että sillä

tikulla |

|

23

vois tehdä semmonen ramppi. |

Figure 7: Player stretches blue stick.

|

24

Hannu onko? to[ssa semmonen

*portai[kko vielä] |

|

25

Matti [↑u:h hh |

|

26

Anna [cool ] |

|

27

Hannu mitä pääsis ylös |

|

28

*(4.0) |

|

29

Kari *eiks tos oo tommonen kynnys. |

|

30

Hannu joo kynnys.* |

|

31

Simo *ai mitä että,= |

|

32

Kari *oliks siinä se kynnys ku mä

aloin jotenkin |

|

33

sen yli yrittää päästä |

|

34

mä en tiedä pääseekö toi port-

tonne |

|

35

(0.4) |

|

36

reen kanssa (.) itessään sitä

*[yli.= |

|

37

Simo

[>niin joo<= |

|

38

Kari =sä voit *kokeilla

tietenkin. |

Kari’s turn (line 22) marks a return to engagement with the game and shows close monitoring of the player’s actions in the virtual space: it is temporally coordinated with Simo’s actions and refers to the specific object (a blue stick) that Simo is currently “touching” in the virtual space (Fig. 7). It also suggests a new solution to the task: using the stick to build ‘a kind of ramp’ (line 23). Next Hannu asks a question that draws attention to another feature of the virtual environment, characterizing it as a staircase (lines 24, 27). Concurrently with this, Simo continues to manipulate the virtual object: he lengthens the blue stick he has been working on, which occasions affective displays from Matti and Anna (lines 25–26). Directing his focus to the task in hand, he does not respond to any of the other participants’ turns, but silently focuses on the task (line 28).

In the next turns Kari and Hannu continue to comment on the visible features of the game area in alignment with each other. Kari offers an alternative way of seeing and interpreting the ‘staircase’ identifying the same feature as a ‘threshold’. His turn, formulated as a negative interrogative, receives an aligning response, a confirmation, from Hannu (line 30). Kari and Hannu’s alternative ways of referring to features of the virtual space contribute to co-constructing the shared interactional space for making sense of the environment and identifying those materials and features that are relevant for advancing the task. While Simo is busy with the objects, he is also attentive to their verbal contributions and now begins to adjust his actions accordingly. He stops handling the blue stick and, concurrently with a verbal initiation of repair, lowers his hands and shifts his gaze again towards the righthand side of the play area. He then continues to scan the environment, while Kari launches into an extended account where he describes how the threshold might be crossed with the vehicle (lines 32–36). The turn expresses his view of a possible solution in a highly tentative way: it contains several uncertainty-markers and is elaborated with a suggestion that Simo ‘can try’ (line 38). The player Simo then picks up the blue stick again and begins to move it. In the next few moments he picks up another stick, which he moves next to the first one to form a kind of ‘ramp’, thus following Kari’s earlier suggestion.

The examples so far illustrate how the participants’ orientations and alignments shift from moment to moment and are temporally adjusted with the changing virtual scenes and the visible actions of the player in control. Forms of participation are structured by the material ecology of the activity; the asymmetrical access to technological and material resources. The visible actions and verbal participation (such as noticings, questions, displays of surprise or uncertainty) of the player in control create occasions for, but do not always engender co-participation. However, observable task trouble generates suggestions and formulations that are acknowledged by the player and consequential for his gameplay actions. Participation is also shaped by spatial arrangements and reflexively tied to social relations between the participants. Two participants seated next to each other build local alignments for commenting on the task (Ex. 2) and suggesting possible solutions by ‘reading’ the game space, noticing its features and drawing attention to them with verbal formulations (Ex. 3). The latter are consequential for the task, as displayed by the subsequent visible displays and actions of the player in control.

Excerpt 4 illustrates how the gameplay unfolds as a collaborative activity between the same three participants. Here Simo’s verbal and visible display of difficulty (lines 60–61) after a failed attempt to build a working ‘ramp’ creates an occasion for both Kari and Hannu to offer assistance by suggesting objects that could be used to build a support structure (lines 62–63, 65–67, 71–72).

Excerpt 4: Possible solution 3: small sticks across the ramp.

|

60

Simo *[£niin kyllä tässä vähän

vaikea |

|

61

ei [oo (iha ei oo hel-) |

|

62

Kari [et #semmoiset pik- pienet

tikut |

|

63

ton rampin yli |

Figure 8: The ramp

|

64

Simo *niin pienet, |

|

65

Hannu *niin (ennemmin) pienemmät

tikut että |

|

66

se pääsee kato porraks-

kynnyksen yli |

|

67

*sieltä.= |

|

68

Simo mutta miten se *pääsee tonne |

|

69

*kun tuo on tolleen ilma[ssa |

|

70

Hannu [pitäskö |

|

71

*siihen laittaa semmosen |

|

72

^tuki: ¤(.) jotai

pilari. |

After Simo’s attempt at using two long sticks to build a ramp for the vehicle fails, all participants join in shared laughter (not shown). Following this and a short side comment by Hannu, Simo comments on the difficulty of the task (lines 60–61) with a laughing voice. In partial overlap with this, Kari steps in and makes a new suggestion: placing small sticks across the ramp (lines 62–63, Fig. 8). Simo immediately acknowledges the suggestion and stops moving the objects he has been handling (line 64). Hannu also joins the team by reformulating the suggestion in a more explicit way: smaller sticks (placed across the two longer sticks that form the ‘ramp’) would help the vehicle cross the threshold (lines 65–67). During Hannu’s turn Simo peruses the virtual space, shifting his gaze from the right back to the left. He seems to be considering the proposal but does not take action to follow it immediately. Instead, he asks a question and uses the controller to point to and touch a virtual object that he refers to in his turn (lines 68–69). In response to this, Hannu makes another suggestion, elaborated by a co-occurring gesture, of making a supporting pillar. From here onwards the activity continues with Simo’s manipulation of the objects following suggestions offered by Hannu and Kari.

The examples from our first case illustrate how several participants form a shared interactional space and contribute to the process of gameplay. Simo’s online commentary and visible embodied conduct show double orientation to the virtual space, in which only he has full access to the environment and ability to manipulate objects and materials, and to the shared physical space where the others can follow his actions via the screen. Simo’s multimodal conduct makes relevant the different but intertwined temporal orientations of gameplay. It displays his here-and-now perceptions and evolving understandings of the virtual play area, its properties and emerging puzzles. In addition, it shows progressive orientation to the overarching goals (constructing a vehicle) and actions that potentially advance gameplay towards the goal. Other participants closely monitor Simo’s efforts, and offer verbal commentary and embodied displays in response to the actions as they become visible on the screen. While two of the participants position themselves as ‘spectators’ (Laurier/Reeves 2014), three take a more active role and two of them, Hannu and Kari, align together and form an interactional team with Simo to assist him with the task. They offer verbal noticings, suggestions and formulations that are temporally fitted to Simo’s gameplay actions, draw attention to specific features of the environment and propose possible solutions to puzzles of the moment. The contributions from these two participants do not challenge Simo’s epistemic primacy (Stivers/Mondada/Steensig 2011, Heritage 2012), that is his relative authority of knowledge, nor his entitlement in performing gameplay actions. The verbal proposals are typically initiated at moments where Simo is visibly having trouble with the task, as indicated by silent embodied and virtual actions (e. g. gaze shifts, visible searching) as verbal expressions indicating difficulty. Further, the utterances are typically formulated as questions or tentative solutions, which show orientation to Simo’s right to make the final decisions and perform actions of his choice.

4.2 Case 2: Mouse in trouble

The second extended instance comes from a game called Moss (Polyarc Inc 2018). The player is in control of the main character, a small mouse, as well as an orb that allows them to interact with objects in the game and assist the main character e. g. by opening doors, moving heavy items and holding down enemies. Also in this case, the main participants are Kari, Simo, and Hannu, only this time Kari is operating the VR-equipment, while Simo and Hannu closely monitor his gameplay. The excerpt begins with the mouse entering a new room containing a puzzle that needs to be solved in order to unlock a path forward on to the next room.

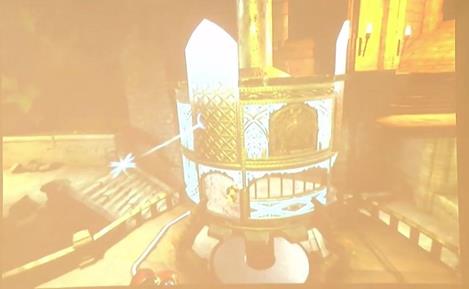

The setup of the room is as follows (Fig. 9): there are stairs to the left (where the mouse entered the scene), a plaza in the middle with a hollow, barrel-like device that contains four closed gates, and a hallway and balcony to the right (where the mouse will exit the room once the puzzle has been solved). Left and right of the barrel are floor-switches that react to weight and keep the barrel’s gates open for as long as the switches stay activated. With the help of the controller/orb, the player can turn the barrel around to change the direction of the gates. In addition, an armored insect is walking around on the left side. The player can interact with the insect, dragging it around or holding it in place. The barrel – in combination with the floor-switches – is the actual puzzle, as the player needs to find a way to navigate the mouse into (and inside) the barrel and through the different gates so that it eventually may reach the balcony on the upper righthand side of the room.

Similar to our first case, also the following example illustrates a double orientation of the primary player as he is acting in the virtual world while mobilizing multiple resources that make his gameplay accountable in the physical space – his actions open up spaces for the others to participate actively in constructing gameplay. However, this case exhibits clear tensions between team- and single-player orientations, as Kari begins to reject suggestions and instructtions that align with his gameplay and with his increasing displays of uncertainty and trouble. The example thus reveals an understanding and recognition of different participation rights in this set-up and for maintaining and drawing on co-presence as an interactive resource.

Figure 9: Set-up of the barrel room in Moss

Immediately after the mouse entered the new room, the player, Kari, directs his gaze to the armored insect sitting in the lower left-hand corner and begins to talk, while moving the orb first to the insect and then to the right to the nearby floor-switch: ‘ok, now this goes here¿’ (line 1):[2]

Excerpt 5: Entering the puzzle: co-constructing joint gameplay

|

1

Kari okei, ^nyt tää menee tähän¿

|

Figures 10 and 11: Pointing with the orb

|

2 (0.5) [vai, ] |

|

3

Simo [aivan. ] [noin ] |

|

4

Kari [^entäs jos ]

mä laitan sen |

|

5 siihen. |

|

6

Simo ^(.) pistä ^sen

siihen. joo. |

|

7

Kari ^(2.0) |

|

8 (vielä.) |

|

9

^(2.0) |

Kari’s ‘ok, now’ marks a clear orientation to the beginning of a new task (line 1). He finely coordinates the movement of the orb with his talk in such a way that it reaches the insect at ‘now this’ and then arrives at the floor-switch precisely at ‘here’ (Figs. 10 and 11). Thus, Kari uses the orb for pointing at the referents of his talk: the indexicals ‘this’ and ‘here’ attain meaning through this form of virtual deictic reference. However, his on-screen activities also indicate movement and project possible action in the game. Similar to Knoblauch (2008: 83), who found for a certain set of pointing practices in powerpoint presentations that “these movements turn the static elements and the parts of the talk into a dynamic process,” here an anticipated process (i. e. the bug moving to the floor-switch) is made observable (see also Bennerstedt/Ivarsson 2010). By doing so, Kari – blind to the physical space and immediate surrounding – displays an orientation to the public visibility of the unfolding game as well as an expectation of the other participants monitoring the ongoing in-game/on-screen actions and following his commentary. While his understanding is ratified by Simo (line 3), Kari continues by bringing up another option, which he now clearly designs as a question (lines 4–5: ‘and what if I put it there.’).

At ‘there’, Kari has brought the orb back to the bug, where it stays hovering for a moment. In close coordination with Simo’s alignment (line 6), he next selects the bug and begins dragging it towards the switch. Thus, he mobilizes a response by observably awaiting and preparing for an affirmation, before actually selecting the bug and beginning to drag it to the right. His actions and public pondering, then, can be seen and are taken by the other participants as an invitation of sorts for them to align with and contribute to the gaming experience – to team up with him – by attending to the puzzle together with him and to confirm his choices. However, as Kari moves on, the participants swiftly transition back to a single-player orientation, where only Kari is in control. At the same time, he continues to verbalize and project (possible) actions, by which he observably treats the others as “still there” and their presence as relevant (lines 10–17):

Excerpt 6: Exploring: publicly experiencing the room

|

10 Kari ^voin mennä samalla itse (.) seikkailemaan. |

|

11

(0.5) ^(mut hetkinen) |

|

12 (0.5) okei, |

Figures 12 and 13: Shift in gaze direction from switch to barrel gates

|

13

^et se ^vielä tarvii ^sitä ^tähä^n. |

|

14 ^(1.5) ja. |

|

15

^(3.0) |

Figures 14 and 15: Leaving the bug behind

|

16

^pysyt ^siinä

ja (.) mä |

|

17

meen ite (tähän toiselle).^ |

As can be seen from the transcript, Kari comments on and even explains his gameplay: ‘I can go wander around myself (.) at the same time.’ (line 10) or ‘you stay [gaze at the bug] there and (.) I myself go (here to the other).’ (lines 16–17, Figs. 14 and 15), while directing the mouse through the room. He also uses gaze and orb-pointing in this passage (line 13), namely after voicing and executing a full stop (‘but wait a second’, line 11), indicating that he ran into or became aware of a problem. He first produces a short ‘okay’ (line 12), after which he moves his gaze first to the right floor-switch and then to the center (the barrel), while concluding, ‘so it still needs this for that.’ (line 13, Figs. 12 and 13). More precisely, Kari’s gaze is finely tuned with his ongoing talk, as it reaches the right floor-switch exactly at ‘this’ (Fig. 12) and the barrel at ‘that’ (Fig. 13). In addition, towards the end of ‘that’ he shortly moves the orb to the barrel, pointing at it before focusing on the mouse on the righthand side again. These deictic practices that are – like in the passage further above – tied to the ecology of action (Mondada, 2014a, 2016), contribute to establishing reference for Kari’s progress and his considerations. Mobilizing multimodal resources, then, Kari not only makes his actions and (different) foci understandable, but he also displays his own understanding of the room’s hidden puzzle (publicly detecting the role of the right floor-switch as another aspect of the riddle that has not been tackled yet). By doing so, he clearly continues to treat the other participants as present, available for collaboration.

Indeed, as Kari proceeds in the game, he is beginning to display task trouble, which increasingly becomes more explicit, prompting the others to step in and gradually reinforce their engagement, i. e. through verbal commentary and suggestions, up to giving distinct instructions. As we will show in our analysis of the following passage, Kari’s public deliberations occasion a transition back from single player to team orientation, where the player in control works as an executor with certain rights that grant him, for example, the final say and allow him to disregard others’ propositions (at least temporarily). In terms of constructing co-presence, these instances are interesting, because they demonstrate how the participants establish and contextualize availability and involvement, and how they make different prerequisites regarding participation and access relevant.

In the beginning of the extract, Kari continues to direct the mouse through the room and onto the right floor-switch, which – now activated – opens two more gates in the barrel. However, he immediately treats the resulting outcome in the game as insufficient (line 19), removes the mouse from the switch (causing the gates to close), moves it first into and then back out of the barrel, and finally into the barrel again (line 20). With the help of the orb, he then selects the barrel, turns it (with the mouse in it, Fig. 16) leftwards and moves the mouse to the left out of the barrel (line 22). His commentary and gameplay further elicit responses by the others that clearly show an orientation towards support and mutual problem solving, i. e. aligning as a team in the presence of Kari’s verbal and nonverbal (bodily as well as on-screen) displays of uncertainty (lines 21–27):

Excerpt 7: Rejection of assistance I

|

18

Kari ^(7.5) |

|

19

eiku,^ |

|

20

^(6.0) |

Figure 16: Kari interacts with the barrel and turns it left

|

21

Simo ^kato. |

|

22

^(2.0) |

|

23

ai:ka

hienosti. |

|

24

Hannu (ja mä

luulen et siin vois tehä ensin |

|

25

¤et mennä sisälle)

|

|

26

^(ja se näkee siit et täs on

ötökkä.)¤ |

Figure 17: Kari looks into the barrel, Hannu points at the screen

|

27 Simo nii. |

|

28

Kari ^mut, |

|

((lines 29–46 omitted)) |

Simo observably affiliates with the on-screen actions, he shows engagement and monitoring (‘look’, line 21) as well as encouragement (‘quite nicely’, line 23) (Baldauf/Colón de Carvajal 2020) in close coordination with Kari’s choices. Hannu, in turn, provides a strategic description of how to possibly proceed with the puzzle (lines 24–26), which is immediately ratified by Simo (line 27). He thereby makes a future orientation visible that corroborates the current issue in the game as ‘still not solved’, reflecting Kari’s ongoing search for a path through the barrel up to the balcony. The design of Hannu’s turn marks it as a proposal, publicly displaying an idea rather than certainty: it is characterized by careful hedging (‘I think’, ‘there one could’), thereby aligning with Kari’s exploring activities. Similar to example 1, Hannu also begins to gesture with his right hand, lifting it up and pointing at the screen with all fingers extended, while moving the hand clockwise in oval-circling motions twice (lines 25–26). This motion is invisible to Kari, but clearly situated in Simo’s visual field. Yet, Hannu’s gesture – closely coordinated with his talk – is interesting, as it simulates anticipated movement of the mouse in the game and clearly is oriented to the architecture of the virtual space. Thus, Hannu can be seen as highly engaged, even briefly assuming an active player’s position by “directing” the mouse through the room himself.

In close coordination with Hannu’s turn, Kari looks into the barrel. In this way, he observably aligns with Hannu’s comment (line 26, Fig. 17). Yet, he does not take up the proposition, but instead initiates a counter argument (‘but’, line 28) and moves on to explore the room, looking around and interacting with the barrel, while commenting on what he sees and does in the game (omitted). At the same time, he gradually enhances his verbal, embodied and in-game displays of uncertainty, involving full stops, question formats, headshakes, and aimless gameplay (e. g. turning the barrel back and forth, looking around). These actions occasion several responses by the other participants, which take on the form of aligned pondering and suggestions, similar to Hannu’s turn in lines 24–26. Interestingly, in addition to this observable team-orientation, where mutual gameplay and group participation are jointly constructed by all three active participants, Kari also keeps up a single player orientation, rejecting his peers’ comments by not implementing their suggestions in his on-screen actions and witnessably trying to proceed “on his own”. He thus positions himself as team member on the one hand, while clearly holding on to being in control on the other hand, displaying an orientation to solving the puzzle alone eventually. As we will show next, Kari even maintains this double orientation after Hannu upgrades his responses in reaction to him exhibiting clear defeat:

Excerpt 8: Rejection of assistance II

|

((lines 29–46 omitted)) |

|

47

Kari ^(1.0) |

|

48

ah::. ^(5.0) |

|

49

(^pitääkö mun nyt tehdä näin.) |

|

50 (3.0)^

^tästä avaudu tää. ((left gates closed)) |

|

51

(1.0) oh my^ ^GO:D. (Fig.

19) |

Figures 18 and 19: Defeat

|

52

Hannu käännä se vielä [¤niinku,] |

|

53

Kari [^JOA, ] nii:n

|

|

54

mun pitää [(vielä),^¤] |

|

55 Hannu

[( )] ( ) |

|

56

Kari ^eikun siis mun mielestä

mun pitäs (ottaa) (.) |

|

57 ton ylös. |

|

58 (1.5) |

|

59 Hannu

niin pistä se ötökkä siihen toisen päälle. |

|

60

Kari >↑NIIn

NIIn.< |

|

61 (1.0)^ |

Kari observably continues in pursuit of a solution (lines 47–50): he looks into the barrel (line 47), produces a change of state token (‘ah::.’, line 48), turns the barrel to the right, stops and directs the mouse out of the barrel to the left side, where he leaves it standing for the time being. Immediately after this, he resumes turning the barrel to the right (line 49). Similar to the earlier passages, these actions are accompanied by commentary that he closely coordinates with what is happening on-screen. Kari notably designs his utterances in the light of the visibility of his gaming actions, drawing on the indexicals ‘this’ and ‘here’, and utilizing the orb for deictic reference (lines 49 and 50, Fig. 18). Mobilizing multiple resources, then, he sustains orientation to the others’ participation and attentiveness, including them in the gaming experience, projecting a possible path to solving the riddle.

However, in the game, some of the barrel’s gates (now facing to the left) remain closed, which prevents the mouse from entering the barrel again to reach the balcony on the upper righthand side of the room. This prompts a strong, emphatic response by Kari (‘oh my GO:D.’, line 51), dropping both hands with the controller to his lap and twisting the head to his left at the end of his turn-constructional unit (simultaneously to ‘GO:D’, Fig. 19). Kari’s embodied expression of failure occasions a directive by Hannu (‘turn it still like ( )’ [pointing movements], lines 52 and 55), thereby treating Kari’s actions – in both, the game and the physical space – as a display of being lost, an occasion to step in and to offer concrete assistance and guidance. The upgrade (from making suggestions to initiating instructions) is indicative of Hannu positioning himself as a knowing participant, which at the same time corroborates his active engagement with the unfolding gameplay in the virtual space. The use of the imperative here implies close monitoring of the ongoing game and of Kari’s prior actions, allowing for a certain understanding of what is going on and how to possibly proceed. However, in overlap with Hannu’s turn, Kari produces an affirmative response (‘YEAH, yes I have to (still),’), stressing the first words of his utterance (JOA, / ‘YEAH,’ and nii:n / ‘yes’), while quickly lifting up the controller and manipulating the barrel again, thus immediately resuming control and (re)claiming epistemic authority (lines 53–54). Next Kari stops moving the barrel and initiates repair (line 56): he voices a change of course (‘or actually I think I should (take) (.) this up’), which he co-produces with the action of turning the barrel to the right, thus changing its direction. This creates a space for Hannu to give more distinct instructions (‘so put the bug there on the other switch.’, line 59) that attend to Kari’s activities as still inadequate. In response, Kari again emphatically claims (>↑NIIn NIIn.< / ‘yes yes.’) competence (line 60). He also explicitly rejects Hannu’s imperative and proceeds turning the barrel to the right (omitted). Eventually the puzzle is resolved, after Hannu’s instructions become more elaborate, and Kari ultimately accepts and implements his advice in the game.

This episode of negotiating epistemic authority is interactively relevant, as the participants navigate between shared gameplay and different rights to making decisions and affecting the course of the game. It demonstrates how the participants position themselves in different ways through construction of certainty and uncertainty, while displaying availability and engagement in the physical as well as virtual space.

The second case illustrates how co-presence is achieved and made relevant in and through shared gameplay involving persistent task trouble. Co-presence in the sense of establishing and maintaining engagement and participation is not only accomplished through verbal, embodied and virtual conduct, but also drawn on as a resource as well as negotiated and carefully balanced with respect to access and participation rights. Throughout the example the primary player ensures – through fine-tuned commentary, gaze and virtual gestures – accountability and projection of his in-game actions. Although Kari does not exclusively draw on the game’s mechanics, this resembles to some extent what Bennerstedt and Ivarsson (2010: 225) describe for teamplay in massively multiplayer online games, namely “that projection should be possible through the reconfiguration of any material” (emphasis in the original). Kari’s activities presuppose careful monitoring by the others, frequently creating opportunities for them to step in and contribute to the course of the game. The participants thus establish a specific participation framework, where Kari is not playing a single-player game alone, but rather can rely on the presence and availability of the other participants as a resource. At the same time, as the passage develops, the interaction exhibits overlapping (and even contrasting) orientations towards teamplay and co-presence and solving the puzzle alone. While Kari continues to display overt uncertainty and even defeat, he does not take up the other participants’ comments and instructions. He observably orients to specific rights as the primary player that allow him to make and implement his own decisions regardless of his co-participants’ engagement or commitment to the game.

5 Discussion

This study illustrates how multiple participants playing a single-player VR game interactively construct co-presence and gameplay across physical and virtual spaces. They employ what Mondada (2018) calls ‘local geography’, such as the material ecology of the setting as well as the participants’ spatial organization, in mutually constructing the play event. Through joint efforts between different actors in the situation, each taking on different roles in its creation at different times, a kind of shared gameplay emerges. The analysis reveals a dynamic similar to Larsen and Walther’s (2019) definition of gameplay as a kind of oscillation between being-here and being-there. Here, we extend the concept by showing how this oscillation happens as a joint activity between co-located actors/players, and how it involves shifting orientations to multiple spaces as well as temporalities as the game unfolds. Shared gameplay is constituted through multimodal actions that display the participants’ orientations to being present in the physical space with one’s co-actors, while interpreting and managing the virtual space of the game in an effort to reach a desired game state, a mutually imagined ‘there’.

The analysis has focused specifically on those moments where the participants establish, sustain and dissolve a team orientation to resolve puzzles faced in the game. These moments are often initiated by the active player’s actions such as noticings and verbal formulations of what is visible on the screen, multimodal expressions of uncertainty or questions addressed to the co-participants. These acts create opportunities for the others to step in and realize their role as active participants by drawing attention to specific features of the virtual game space visible through the external screen, by offering their understandings of potential solutions to problems and making suggestions or even giving instructions.

The other participants’ actions are temporally closely coordinated with the unfolding gameplay and sensitive to the social organization of the situation. They are also consequential for gameplay: the player in control may adjust or alter their actions in response to new observations or understandings of a specific puzzle and follow suggestions offered by others. The player may also explicitly reject the attempts to influence their choices, challenge or disagree with them, and make explicit their primary rights to make decisions about gameplay. We argue that in both cases, the other participants work to interactively position themselves in multiple interactional spaces and thereby reconfigure these spaces. This way, they also create new contextual configurations for actions to follow. They simultaneously participate in co-creating gameplay and the game event, and stand outside of it.

The findings illustrate how participants are sensitive to the active player’s primary rights to perform and make decisions about gameplay actions. This is visible both in the sequential environments in which they initiate talk, and in the way that their turns are formulated. Occasions for interaction often occur at moments where the active player has expressed some trouble or recruited participation from others through verbal and/or embodied displays. Through their linguistic design, other participants’ turns that comment on and aim to influence gameplay are often formulated as tentative suggestions that attend to the active player’s epistemic primacy (Stivers/Mondada/Steensig 2011) and align with their efforts to resolve troubles in gameplay.

Our analysis further illustrates that achieving team orientation is not frictionless. The data shows participants engaged in constant negotiation of who has the right to act, when, and how. For example, the active player may show irritation at others giving ‘obvious’ advice, and other participants may design their turns as overtly tentative or polite when trying to influence the active player. Put simply, shared gameplay requires constant interactional work and is related to the social relations between the players.

The findings challenge views of presence that contrast face-to-face and virtual spaces and conceive virtual reality games as immersive and distinct from the physical and material surround in which they are played. Rather, similarly to earlier studies of multimodal interaction in technosocial environments (e. g. Keating/Sunakawa 2010, 2011), the analysis sheds light on the diverse and often creative modes of participation that enable the participants to create coherent play across the ‘real world’ and virtual game world. In situations where multiple participants come together to play single player VR games, we argue that it is precisely the dynamic interplay of building co-presence in multiple spaces that creates occasions for playful enjoyment and sociality around the game. Here, then, is a possible link between how both co-presence and gameplay may be co-constructed, and how their construction may benefit each other. While a player playing a single-player game alone might spend long moments in silence, pondering on their next move, the fact that there are other participants present makes gameplay publicly observable and accountable. The player orients to this both verbally (for instance by verbalizing what might otherwise be internal thoughts) and through bodily conduct (utilizing virtual gestures, visibly searching the game space). This creates occasions for different forms of co-participation and makes visible the oscillation between more structured and organized activity (game) and a more open-ended and fluid activity (play). What our study shows is that the physical presence of other participants allows the active player to draw on them as a resource. It also shows how the material ecology structures forms of participation in specific ways. This is seen in particular in the way that other participant’s turns and actions are fitted to the unfolding game scenes and actions on the shared screen.

The impact of spectators or other participants on gameplay has been seen from different perspectives in earlier literature. Some authors have proposed that having other people present during gameplay could interrupt the flow of the player and “knock players out of their fantasy game worlds” (Sweetser/Wyeth 2005: 10). Others have highlighted how introducing other actors into the setting may boost player enjoyment (Gajadhar/De Kort/Ijsselsteijn 2008) and involvement (Gajadhar/De Kort/Ijsselsteijn 2009). In Gajadhar et al.’s (2009: 14) words: “… co-players do not break the spell of the game, but become a part of the magic circle.” Our analysis leans more on the latter kind of effect, where the other participants are not so much of a liability as they are a potential resource. Therefore, we propose an approach to understanding gameplay that does not try to construct fixed typologies of different kinds of participants, but rather appreciates the many ways in which multiple participants may jointly create the play event even in instances of playing a game designed for a single player.

6 References

Arminen, Ilkka/Koskela, Inka/Vaajala, Tiia (2008): Configuring Presence in Simulated and Mobile Contexts. In: Anna Spagnolli/Luciano Gamberini (eds.): PRESENCE 2008. Proceedings of the 11th annual international workshop on presence. Padova: CLEUP Cooperativa Libraria Universitaria Padova, 129–136.

Baldauf-Quilliatre, Heike/Colón de Carvajal, Isabel (2015): Is the Avatar Considered as a Participant by the Players? A Conversational Analysis of Multi-Player Videogames Interactions. In: PsychNology Journal 13 (2–3), 127–147.

Baldauf-Quilliatre, Heike/Colón de Carvajal, Isabel (2020): Encouragement in Videogame Interactions. In: Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 2 (2).

https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v2i2.118041 [retrieved April 2020]

Baldauf-Quilliatre, Heike/Colón de Carvajal, Isabel (this issue): Spectating: How non-players participate in videogaming.

Bennerstedt, Ulrika (2013): Knowledge at Play: Studies of Games as Members’ Matters. PhD thesis. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, Acta Universitatis Gothenburgensis.

Bennerstedt, Ulrika/Ivarsson, Jonas (2010): Knowing the Way. Managing Epistemic Topologies in Virtual Game Worlds. In: Computer Supported Cooperative Work 19, 201–230.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-010-9109-8

Gajadhar, Brian/de Kort, Yvonne/IJsselsteijn, Wijnand (2008): Shared Fun is Double Fun: Player Enjoyment as a Function of Social Setting. In: Markopoulos, Panos/de Ruyter, Boris/IJsselsteijn, Wijnand/Rowland, Duncan (eds.): Fun and Games. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 106–117.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-88322-7_11

Gajadhar, Brian/de Kort, Yvonne/IJsselsteijn, Wijnand (2009): Rules of Engagement: Influence of Co-Player Presence on Player Involvement in Digital Games. In: International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations 1 (3), 14–27.

https://doi.org/10.4018/jgcms.2009070102

Goffman, E. (1966). Behavior in public places. New York: Free Press.

Goodwin, Charles (2000): Action and Embodiment Within Situated Human Interaction. In: Journal of Pragmatics 32, 1489–1522.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

Goodwin, Charles (2007): Participation, Stance and Affect in the Organization of Activities. In: Discourse & Society 18 (1), 53–73.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926507069457

Goodwin, Charles (2013): The Co-operative, Transformative Organization of Human Action and Knowledge. Journal of Pragmatics 46, 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.09.003.

Haddington Pentti/Keisanen, Tiina/Mondada, Lorenza/Nevile, Maurice (2014): Multiactivity in Social Interaction. Beyond Multitasking. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Heidegger, Martin (1996) [1927]: Being and Time. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Heritage, John (2012): The Epistemic Engine: Sequence Organization and Territories of Knowledge. In: Research on Language and Social Interaction 45 (1), 30–52.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.646685

Isbister, Katherine (2010): Enabling Social Play: A Framework for Design and Evaluation. In: Bernhaupt, Regina (ed.): Evaluating User Experience in Games: Concepts and Methods. London: Springer, 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84882-963-3

Jørgensen, Kristine (2012): Players as Coresearchers: Expert Player Perspective as an Aid to Understanding Games. In: Simulation & Gaming 43 (3), 374–390.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878111422739

Keating, Elizabeth/Sunakawa, Chiho (2010): Participation Cues: Coordinating Activity and Collaboration in Complex Online Gaming Worlds. In: Language in Society 39, 331–356.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404510000217

Keating, Elizabeth/Sunakawa, Chiho (2011): A Full Inspiration Tray: Multimodality Across Real and Virtual Spaces. In: Streeck, Jürgen/Goodwin, Charles/LeBaron, Curtis (eds.): Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 194–206.

Kendrick, Kobin/Drew, Paul (2016): Recruitment: Offers, Requests, and the Organization of Assistance in Interaction. In: Research on Language and Social Interaction 49, 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1126436

Knoblauch, Hubert (2008): The Performance of Knowledge: Pointing and Knowledge in Powerpoint Presentations. In: Cultural Sociology 2 (1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975507086275

Laurier, Eric/Reeves, Stuart (2014): Cameras in Video Games: Comparing Play in Counter‐Strike and the Doctor Who Adventures. In: Broth, Mathias/Laurier, Eric/Mondada, Lorenza (eds.): Studies of Video Practices: Video at Work. New York: Routledge, 181–207.

Larsen, Lasse/Walther, Bo (2019): The Ontology of Gameplay: Toward a New Theory. In: Games and Culture. [online first February 2019] https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019825929

Lilja, Niina/Piirainen-Marsh, Arja (2019): How hand gestures contribute to action ascription. Research on Language and Social Interaction 52 (4), 343–364.

http://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1657275.

Lombard, Matthew/Ditton, Theresa (1997): At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence. In: Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 3 (2).

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x

Mondada, Lorenza (2012): Coordinating Action and Talk-in-Interaction In and Out of Video Games. In: Ayaß, Ruth/Gerhardt, Cornelia (eds.): The Appropriation of Media in Everyday Life. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 231–270.

https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.224

Mondada, Lorenza (2013). Coordinating Mobile Action in Real Time: The Timely Organization of Directives in Video Games. In: Haddington, Pentti/Mondada, Lorenza/Nevile, Maurice (eds.): Interaction and Mobility: Language and the Body in Motion. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 300–344. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.187

Mondada, Lorenza (2014a): The Local Constitution of Multimodal Resources for Social Interaction. In: Journal of Pragmatics 65, 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

Mondada, Lorenza (2014b): Conventions for multimodal transcription. https://franz.unibas.ch/fileadmin/franz/user_upload/redaktion/Mondada_conv_multimodality.pdf

Mondada, Lorenza (2016): Challenges of Multimodality: Language and the Body in Social Interaction. In: Journal of Sociolinguistics 20 (2), 2–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.1_12177

Mondada, Lorenza (2018): Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality. In: Research on Language and Social Interaction 51 (1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878.

Mäyrä, Frans (2008): An Introduction to Game Studies: Games in Culture. London, England: SAGE.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446214572

Piirainen-Marsh, Arja (2012): Organising Participation in Video Gaming Activities. In: Ayaß, Ruth/Gerhardt, Cornelia (eds.): The Appropriation of Media in Everyday Life. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 195–230. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.224.

Polyarc Inc (2018). Moss. https://www.polyarcgames.com

Radial Games (2017). Fantastic Contraption.

https://www.fantasticcontraption.com

Reeves, Stuart/Greiffenhagen, Christian/Laurier, Eric (2017): Video Gaming as Practical Accomplishment: Ethnomethodology, Conversation Analysis, and Play. In: Topics in Cognitive Science 9 (2), 308–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12234

Sjöblom, Björn (2011): Gaming Interaction: Conversations and Competencies in Internet Cafés. Linköping Studies of Arts and Sciences 545. Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press.

Stenros, Jaakko/Paavilainen, Janne/Mäyrä, Frans (2009): The Many Faces of Sociability and Social Play in Games. In: Proceedings of the 13th International MindTrek Conference: Everyday Life in the Ubiquitous Era, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1145/1621841.1621857

Stivers, Tanya/Mondada, Lorenza/Steensig, Jakob (eds.) (2011): The Morality of Knowledge in Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511921674

Streeck, Jürgen/Hartge, Ulrike (1992): Previews: Gestures at the transition place. In: Auer, Perer/Di Luzio, Aldo (eds.): The contextualization of language. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins, 138–158. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.22

Sweetser, Penelope/Wyeth, Peta (2005): GameFlow: A Model for Evaluating Player Enjoyment in Games. In: ACM Computers in Entertainment 3 (3), 1–24. Article 3A.

https://doi.org/10.1145/1077246.1077253

Tekin, Burak S./Reeves, Stuart (2017): Ways of Spectating: Unravelling Spectator Participation in Kinect Play. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’17), 1558–1570. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025813

Appendix

The transcripts follow the transcription conventions established by Gail Jefferson. The description of multimodal details complies to the principles of multimodal transcription developed by Lorenza Mondada:

|

. |

falling intonation contour |

|

, |

level intonation contour |

|

¿ |

slightly rising intonation contour |

|

? |

rising intonation contour |

|

↑ |

sharp rise in pitch |

|

↓ |

sharp fall in pitch |

|

minä |

emphasis |

|

JOA |

strong emphasis |

|

[ |

beginning of simultaneous talk |

|

] |

end of simultaneous talk |

|

(.) |

micropause |

|

(0.5) |

silences in tens of a second |

|

(( )) |

transcriber’s comments, descriptions of nonverbal actions |

|

: |

preceding sound is stretched |

|

se- |

glottal stop or cut off |

|

°joo° |

whispered talk |

|

= |

latches between words or turns |

|

>joo< |

increased speech rate |

|

<joo> |

decreased speech rate |

|

.joo |

word produced with inhalation |

|

.h |

audible inhalation |

|

h |

audible aspiration |

|

( ) |

uncertain hearing |

|

£nih£ |

smiley voice |

|

|

|

|

* |

embodied actions by Simo |

|

^ |

embodied actions by Kari |

|

¤ |

embodied actions by Hannu |

|

# |

embodied actions by Matti |

|

*---> |

the embodied action continues across subsequent lines… |

|

--->* |

…until the same symbol is reached. |

|

--->> |

the embodied action continues after the excerpt’s end |