Vol 3 (2020), No 1: 57–93

DOI: 10.21248/jfml.2020.34

Open peer review available at: http://dp.jfml.org/2020/opr-luginbuhl-schneider-medial-shaping-from-the-outset/

Medial Shaping from the Outset: On the Mediality of the Second Presidential Debate, 2016

Abstract

In the present article we argue that all communication is medial in the sense that every human sign-based interaction is shaped by medial aspects from the outset. We propose a dynamic, semiotic concept of media that focuses on the process-related aspect of mediality, and we test the applicability of this concept using as an example the second presidential debate between Clinton and Trump in 2016. The analysis shows in detail how the sign processing during the debate is continuously shaped by structural aspects of television and specific traits of political communication in television. This includes how the camerawork creates meaning and how the protagonists both use the affordances of this special mediality. Therefore, it is not adequate in our view to separate the technical aspects of the medium, the ‘hardware’, from the processual aspects and the structural conditions of communication. While some aspects of the interaction are directly constituted by the medium, others are more indirectly shaped and influenced by it, especially by its institutional dimension – we understand them as second-order media effects. The whole medial procedure with its specific mediality is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition of meaning-making. We distinguish the medial procedure from the semiotic modes employed, the language games played and the competence of the players involved.

Keywords: mediality, medial shaping, procedures of sign processing, technique, presidential debate, political communication in television

0. Introduction

We argue that all communication is medial in the sense that every human sign-based interaction is shaped by medial aspects from the outset, and we propose a dynamic, semiotic concept of media that focuses on the process-related aspect of mediality: media can be understood as social procedures of sign processing. We criticize the reification of media by arguing that all media are technical media, but the technical aspect cannot be reduced to materiality. Our dynamic concept takes into account the narrow link between ‘sign’ and ‘medium’[1] in social interaction and is therefore relevant as a theoretical and methodological basis of multimodal interaction analyses.

We test the applicability of the proposed definition using as an example the second presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump in 2016, which shows how the spatial arrangement and camerawork create meaning and how the protagonists both use the affordances of this special mediality and have their behavior shaped by it. The analysis also demonstrates that, even in this staged situation, face-to-face communication must already be regarded as an inescapable medium of human communication and has a mediality from the outset.

1. Theoretical Discussion

1.1 The Concept of Media in Everyday Language and Science

The word medium has many different usages in everyday language. Three of the most interesting and relevant are the following:

a) a thing or pure matter (the material aspect), as either a machine, an apparatus, a device or hardware (e. g. computer, smartphone, television, typewriter), on the one hand, or a ‘carrier medium’ (e. g. sound waves, paper, blackboard, overhead transparency), on the other;

b) an institution (the institutional aspect): “So you want to work in the media”;[2]

c) a potential or process in which something, especially meaning, is constituted or generated (the process aspect): He “knew how to express himself in the medium of paint”.[3]

These three aspects correspond to three traditional meanings of the word medium in the history of Western thought (cf. Margreiter 2003: 152; Lagaay/Lauer 2004: 9 f.; Münker/Roesler 2008; Münker 2008):

a) the medium as a means to an end or a tool;

b) the medium as the middle or ‘the in-between’: the place of encounter that brings people and different things together (cf. Margreiter 2003: 152; Münker 2008: 322 f.);

c) The medium as (a necessary condition of) mediation.

Recent media theories and research on mediality thematize and discuss all three aspects. They have been strongly influenced by Marshall McLuhan (1964), who defines media as extensions and substitutes of the human body and sensory performance. This definition is extremely broad: for example, eyeglasses, the microscope and the camera extend or replace the eye; clothing expands our skin; a telephone expands our speech organs, and so on. This understanding of media finds its origins in the philosophy of technology of Ernst Kapp and Arnold Gehlen. According to Kapp and Gehlen, ‘technique’ consists of objectified, outsourced body functions, and all technical artefacts are projections of our organs (cf. Margreiter 2003: 153).

Another crucial point in McLuhan’s theory is that the mediality of a medium is normally not perceived: we use the medium, talk about it ideologically, but what we do not see or recognize is its mediality, i. e. the ways it shapes the choice of signs and how we use them, and therefore its materiality and processuality (cf. Margreiter 2003: 153). Media have a tendency to make themselves invisible (cf. Krämer 1998). This tendency shapes the mediation process: media do not merely transport something, but are instead part of the way in which sense is produced and constituted; precisely because they have a tendency to become invisible, they imperceptibly leave their traces on the respective message (cf. Jäger 2004, 2012, 2015; Linz 2016; Luginbühl 2015, 2019; Schneider 2006, 2008; Stetter 2005). Krämer’s trace theory can be understood as a moderate reading of McLuhan’s “The medium is the message”. But while McLuhan holds the deterministic view that “cool” media have a different effect than “hot” ones, other media theorists today have pragmatized his theory (cf. Sandbothe 2001; Bolter/Grusin 2002): whether a medium is cool or hot depends not only on its mediality, but also on how we use it. Accordingly, Jay David Bolter and Robert Grusin define a medium as “[t]he formal, social, and material network of practices that generates a logic by which additional instances are repeated or remediated, such as photography, film or television” (Bolter/Grusin 2002: 273, italics added).

Furthermore, media theories and research on mediality consider not only the processual and material aspects of media, but also the institutional aspect. “New institutionalism” conceptualizes not only media, especially mass media, but also social media like Facebook and Twitter as institutions in order to compare and relate them to other institutions like family, church, school and government: “[...] it can be argued that the mass media have emerged as a social institution, fulfilling many of the functions that are no longer being served by traditional social institutions such as the family, church, and school” (Silverblatt 2004: 39). Shoemaker and Reese describe the interweaving of mass media and other social institutions in modern societies, especially the US, on the basis of this view: “Indeed, we assume media cannot be understood except in relation to other fields” (Shoemaker/Reese 2014: 99; cf. Cook 1998; 2006; Sparrow 1999; Schudson 2003; 2018).

Journalism was often perceived as an independent, objective authority, and this view promoted a separation between journalism and social institutions (cf. Shoemaker/Reese 2014: 98). But the two cannot be separated at all, of course: mass media have never represented reality ‘objectively’, but are themselves ‘political actors’ – something that has long been pointed out in media sociology and mass media and communication studies (e. g. Gans 1979; Cook 1998; Sparrow 1999; Schudson 2003; Shoemaker/Reese 2014), in cultural studies (e. g. Hartley 1982; Hartley/Montgomery 1985; Fiske 1987; Morley 1992; Fairclough 1995) and in media linguistics (Straßner 1975; Schwitalla 1979; Holly/Kühn/Püschel 1986; 1989; Jucker 1986; Schegloff 1988; Greatbatch 1998; Clayman/Heritage 2002; Holly 2004).

According to Shoemaker and Reese (2014: 100), this view of media as “an institutional actor allows us to take it seriously in relation to other key political institutions”. Generally speaking, considering mass (as well as social) media as social institutions makes it possible to compare them with other key institutions. Following Bourdieu’s field theory, Shoemaker/Reese stress that economic and cultural capital interact in the various ‘fields of action’ with which mass media and other institutions are intertwined: “Modern societies, through the interplay of economic and cultural capital as forms of power, develop specialized spheres of action, or fields, which have their own relative autonomy and power dynamics among them” (Shoemaker/Reese 2014: 101). In journalism, media institutions can be culturally or economically rich, and sometimes both (Shoemaker/Reese 2014: 102). The same is true of various television channels and political talk show and discussion formats that combine economic and symbolic capital in different ways.

According to Luginbühl (2019: 128), political television discussions are subject to a threefold logic. First, they function as a fourth estate (cf. Hanitzsch 2007: 373 f.), a potential political corrective. Second, they enable the filmed protagonists to present themselves in as positive and successful a light as possible. And finally, they must entertain the audience. In this threefold way, the medium of television is thus a political actor: it presents oral interactions that are shaped from the outset by the institution of television and the media format of television discussion. Without the medium of television, these interactions would never take place in this way, as a result of which the medium not merely transmits the content, but becomes an actor in its own right. As we show below in our analysis of the second US presidential debate in 2016, the medium of television is a political institution; it shapes not only the spatial arrangements and the camerawork, but also the conversation itself, including aspects like turn-taking, topic treatment and presentation of self and others.

The view that media are institutions fits with the view of language as a medium, because language was also conceived of as an institution early on by some of the most influential linguistic theorists. For both Whitney and Saussure, the language system – for Saussure, la langue – is a social institution. This view implies that there is no strict conceptual separation between mass media and semiotic media such as languages, because both are social institutions. For Saussure, there is a dialectical interplay of langue and parole (language use) at both the social and individual levels: the language system can only develop by being used socially by individuals, and at the same time all language users participate in the social institution “langue”. However, langue can only exist in a more or less stable way if the linguistic schemata are internalized in individuals’ language “depots” (see Saussure 1967: 383 f. Jäger 2010: 188 f.). The langue is “a kind of average” (“une sorte de moyenne”; de Saussure 1972: 29) between speaking individuals.

According to Ryfe (2006: 137), “[i]nstitutions mediate the impact of macro-level forces on micro-level action”. They are a necessary condition for social systems and communication. Mass media as social institutions and as a “networked public sphere” (Shoemaker/ Reese 2014: 98) can be used to overcome spatial distances. Similarly, the standardization of languages goes hand in hand with the possibility of inter-regional communication. Another similarity between languages and other social institutions is that they are all based on social conventions, rules and habits, and thus possess an inherent normativity (cf. Silverblatt 2004: 37 f.; Austin 1975: 12–46). Just as a speech act is based on conventionalized felicity conditions (cf. Austin 1975: 14–15), there are also conventionalized patterns of action and customs in other social institutions (e. g. one should get to school on time, parents are responsible for their minor children and the government can enact laws to be obeyed).

1.2 A Plea for a Process-related Understanding of Media

As the previous considerations have already shown, in both everyday language and scientific discourses the concept of media includes material, processual and institutional aspects. Nevertheless, there has always been a tendency to reify media and reduce them to their material aspect. In some media theories, the term medium is still used to refer to only the matter used to ‘transport’ meanings, information or signals from a sender to a receiver. Especially in German media discourse, but also internationally, this technical conception of media is still dominant in linguistics (cf. Marx/Weidacher 2014: 54; Schmitz 2015: 8) and some media studies works (e. g. Hartley’s widely read introduction to Communication, Cultural and Media Studies (2020: 200): “Media of communication are therefore any means by which messages may be transmitted”). Leeuwis (2004: 118) focuses on media as apparatuses combining communication channels that exist “for the ‘transportation’ of visual, auditive, tactile and olfactory signals”; in his view, communication media are “composite devices which incorporate several channels at once”. On the one hand, this is a technical concept in the narrower sense; on the other hand, Leeuwis (2004: 118), along with Schmitz and Marx/Weidacher, emphasizes the idea of potentiality when he discusses media as incorporations of channels that “allow for” communicative applications.

In our opinion, the technical aspect of media can be integrated more adequately if a broader concept of technology is used that does not reduce the term to hardware, but instead includes the meaning of the word technique. As Winkler (2008: 91) points out, this broader concept has its origin in Greek philosophy, where téchne referred to certain practical skills, for instance the skill of painting or making music. In ancient rhetoric, elocution skills were also understood as ‘téchne’, something between a pure instrumental technology and an esthetic art (Gutenberg 2001: 146). This skill-related aspect is clear in English, as examples in dictionaries show (“I used a special technique to make the bread”, Merriam-Webster online, emphasis in original).

If we employ a concept of media that takes into account both the material and the procedural aspects of technology/technique, we can say with Winkler (2008: 91) that all media are technical. We understand media as socially constituted procedures of sign processing (Schneider 2008, 2017). This definition first implies that media always have to do with communication and the mediation of signs (cf. Stetter 2005; Margreiter 2003: 154). Thus, this understanding of media is narrower than McLuhan’s, who sees even a street, a wheel, glasses and a microscope as media, but broader than the technical definition, which only focuses on hardware, apparatuses and sign transmission.

Although media always have a material and ‘apparative’ side, a medium cannot be reduced to its technical aspect in the narrow sense. From this perspective, it becomes possible to dissolve the reifying concept of media and at the same time always include in it the material basis of mediality: as Christian Stetter puts it, a medium can be seen as “a procedure operating over an apparatus of any kind” (Stetter 2005: 91, our translation). This apparatus or apparatuses, “bodily or apparative substrates” (72), can be of very different kinds: our speech organs, a typewriter, a computer and so on. In the same publication, Stetter also defines a medium as “an apparatus set in operation, so that through this operation something is created, namely a representation of a certain form” (Stetter 2005: 74, our translation). In our understanding, these two formulations represent two sides of the same coin: a procedure operating over an apparatus can also be seen as an apparatus set in operation. This model of the dialectical interplay of procedure and apparatus is also consistent with Winkler’s thesis that all media are technical (in the broader sense). If one adopts this way of seeing, even a computer can be regarded as a medium without necessarily being reified. For only a computer that is switched on functions as a medium (cf. Schneider 2017: 37). In reference to social media, Münker (2013: 252) argues “that some media exist only due to their use”. We reformulate this thesis: all media exist only due to their use. Our comprehensive understanding of media – and this is crucial – does not imply that we do not have to make further analytical distinctions in empirical studies in order to understand media procedures in detail. But it does make it possible to see that mediality is relevant at different analytical levels, and that it always includes a procedural and a material aspect.

A specific feature of this process-related understanding of media is the proximity of sign system and medium – the two terms describe one and the same multi-faceted phenomenon from different perspectives (cf. Margreiter 2003: 155). If we analyze sign systems or semiotic modes ‘technically’, if we consider them from the perspective of their mediality, i. e. their materiality and processuality, then we look at them as media or medial procedures (Schneider 2008, 2017, following Margreiter 2001: 4). The specific way in which a given medium processes signs defines its mediality. Processing here means not only mediation, but also constitution. The sign with its potential for meaning and its material qualities cannot be separated from its medial processing.

This process-related view of mediality makes it clear that we should not reify media by looking for things that can be categorized as media, but should instead look at the medial processes that are involved in each case (cf. Jäger 2015: 110). How can the mediality[4] of a given medial procedure be described? For example, what structural conditions are specific to the medial procedure of face-to-face communication? What effects does mediality, i. e. the characteristics of a given medial process, have on communication? Seen in this light, ‘medium’ is a typical “zoom concept” (Hermanns 2012: 269) in which the “scopus” can be set differently, the granularity can differ depending on the particular research interest. If the medium ‘spoken language’ is to be compared with the medium ‘written language’, the scopus is relatively wide and coarse; a comparison between face-to-face and telephone communication is narrower, and a comparison between landline telephony and mobile telephony is narrower still. The medial procedure is characterized by its mediality, i. e. by its medial properties or structural communication conditions. It opens up specific latitudes that communicators can use. Thus we always have a certain freedom of action under the specific media conditions. At the same time, however, the media infrastructure shapes what we can do: it is always and inevitably part of meaning production. It is this relationship between the possibilities and limitations given by a media infrastructure, on the one hand, and the way people use this scope for their communicative purposes, on the other, that is addressed by the concept of media affordances (cf. Zillien 2008; Hutchby 2014).

McLuhan denies such freedom of action and takes a deterministic view: “McLuhan’s own theory is not interested in exploring what we do with media – it is interested in describing what media do with us. And what media do is to shape, according to their technical properties, the people who use them as well as the content they transport” (Münker 2013: 247, emphasis in original). In Münker’s view, McLuhan’s – and Kittler’s – “media-technological determinism simply misreads the relationship between the technology and the use of media by interpreting the necessary condition of media technology for any media usage as a sufficient condition” (Münker 2013: 250). Even mediality as a whole is not a sufficient, but only a necessary condition of media usage.

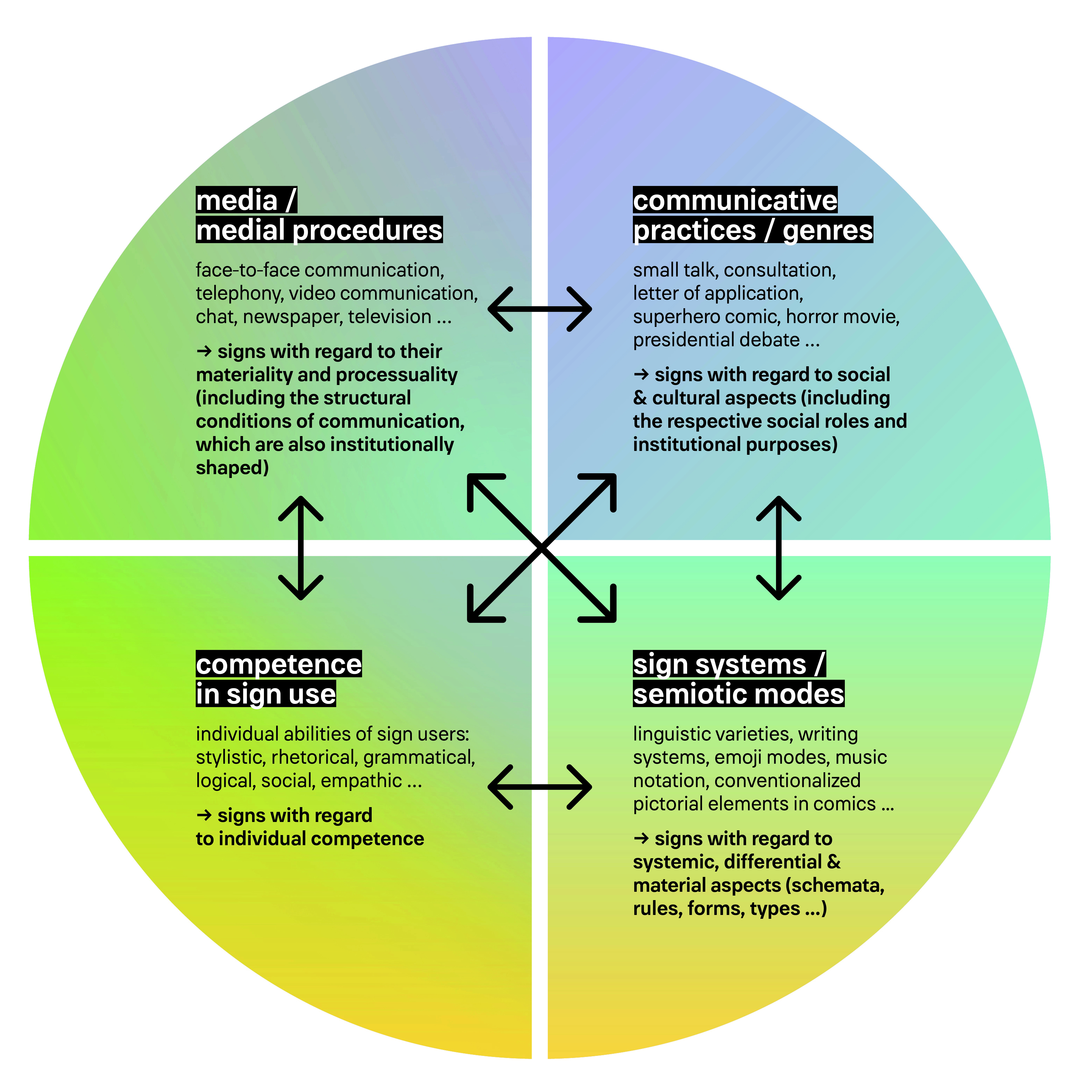

The crucial point is this: for scientific analysis, a distinction must be made between (a) mediality, i. e. the possibilities of the medium, (b) the sign systems/semiotic modes employed, (c) the communicative practices (language games in a Wittgensteinian sense)/genres and (d) the skills of the players. The following diagram (see also Schneider 2017: 45) integrates these four interacting aspects of human sign use:

Figure 1: Four dimensions of human sign use

The arrows pointing in both directions mean that in the concrete use of signs the four dimensions of human communication interact. In practice, they are inseparable and interdependent; only analytically can they be distinguished from each other as aspects of one and the same process, and even analytically it would not be appropriate to draw sharp boundaries between them.[5] No matter which of the four aspects one starts with in an analysis, one automatically reaches the other three. The mediality of traditional (landline) telephony, for example, allows simultaneous interaction between spatially absent persons in fixed locations using the oral signs of a given language; in this medium, numerous culturally grown language games can be played (e. g. private telephoning with friends, telephone negotiations, making appointments). A further question is how skillfully individuals master these medially shaped practices – how well they can, for instance, negotiate on the telephone.

Contrary to the deterministic view, then, we argue that there is a strong interdependence between mediality and media use. On the one hand, media contour the use of signs; on the other, individual and social use changes the media.

1.3 All Media are ‘Technical’: The Inescapability of Sign Use

As we have outlined above, face-to-face communication can also be regarded as a medium or a medial procedure with a certain mediality. This view overcomes the traditional notion of medialess communication, which separates things that belong together. In our opinion, there is no such thing as non-medial communication.

Some theorists refer to interpersonal communication (especially face-to-face communication) when referring to synchronic exchange between communicating persons. If these persons interact at the same time and in the same place, we have a case of face-to-face communication. For our discussion, it is important that face-to-face communication is usually not considered a medium. Leeuwis (2004: 196), for instance, calls face-to-face communication “non-mediated”. When referring to “interpersonal ‘media’”, therefore, he places the word media in quotation marks. However, studies in conversation analysis discuss the mediality of face-to-face communication, even though they do not explicitly refer to oral language as a medium (cf. Auer 2009; Becker-Mrotzek 2009; Imo/Lanwer 2019).

In German media linguistics, face-to-face communication is usually not seen as medial or as a medium but – along with, for example, telephony, chat and weblogs – a “communication form” (for a recent discussion of this concept, see Brock/Schildhauer 2017a). The term communication form usually concerns the structural conditions of communication provided by the medium, e. g. ‘uni-directional’ versus ‘bi-directional’, ‘synchronous’ versus ‘asynchronous’, ‘spatially absent’ versus ‘spatially present’ (cf. Brinker 2005: 147). These are, indeed, important pairs of terms through which to analyze medialities, and there are various approaches describing conditions like these precisely (e. g. Meiler 2018; see also the contributions in Brock/Schildhauer [eds.] 2017a) – but in our view they can be seen as dimensions of the medial procedure. The concept of communication forms was – for good reasons – originally introduced to describe the structural conditions of communication that could not be captured by a narrow definition of media (see also Schneider 2017: 8–12), but the process-related definition of media includes these structural conditions.[6] In mass-media communication, for example, there is no separation between interpersonal communication and technically mediated communication in the medial procedure. In television discussions, for example, the medial procedure of oral interaction is technically and medially shaped from the outset. As we will see in the empirical section below, this shaping happens, for example, through spatial staging and camerawork.

But the crucial point here is the following: even (unfilmed, ‘natural’) face-to-face communication is medial and ‘technical’ in a broader sense. This view makes it possible, for example, to compare the medial procedure of face-to-face communication (not for broadcast) with the medial procedure of television discussion. That these are two different sign-processing procedures would be occluded if we were to regard face-to-face communication as media-less. Always considering sign use as medially shaped is a precondition for contextualizing and comparing all kinds of sign use. This opens up new horizons for analysis and overcomes the division between phenomena that are actually inseparable. In Section 1.1, we observed something similar with the concept ‘institution’: by understanding media as institutions, we can see how they are related to other institutions, e. g. political ones. In the same way, understanding face-to-face communication as a medium makes it possible to compare it with other media and work out interesting similarities, connections and differences.

The traditional belief that interpersonal communication, especially face-to-face communication, is non-medial was, in our opinion, based on the ‘myth of authenticity’: face-to-face communication was regarded as genuine and authentic, while written communication acts and acts that depend on human-made devices (e. g. telephoning or watching television) tended to be branded as artificial. But this view is misleading: since the use of signs is fundamental for meaning-making from the outset, there are no completely objective representations; rather, every form of communication and representation is semiotically and medially shaped and thus perspectival.

The remainder of this article is devoted to the analysis of a media event that was watched live by about 66.5 million television viewers (Serjeant/Richwine 2016) and streamed by probably more than 100 million Internet users (Granados 2016): the second presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump on October 9, 2016. We do not analyze this debate in terms of content or politics, but instead the media process in which the debate took place. Our aim is to offer an exemplary analysis that builds on research done on older and other similar debates (e. g. Schroeder 2000; Bucher 2007; Krebs 2007; Denton 2017), but which still needs further refinement with more data. Roughly speaking, what we are dealing with here is a live, unidirectional, mass-media broadcast that encompasses several partial formats, including one-to-many monologues and face-to-face, side-by-side and split-screen communication. As in any face-to-face communication, the oral communication used here is sequential, multimodal and ephemeral. At the same time, however, it is recorded and thus made repeatable for all time. In addition, the presidential debate is not only characterized by its complex mediality, but also institutionally shaped from the outset, because the footage was produced by certain television stations, in this case NBC, CBS and C-SPAN, countless other mass media (television and radio stations, print media, social media) are involved and the entire staging and script are subject to strictly defined regulations. While some aspects of this interaction are directly constituted by the medium, others are more indirectly shaped and influenced by it; we refer to the latter as second-order media effects.

2. Empirical Discussion

As elaborated above, we understand every communication as mediated and all sign use as shaped by the mediality of the medium in use. Apart from a material aspect that includes technical possibilities and restrictions, we understand the concept ‘medium’ to also include processual, institutional and cultural aspects. Political TV debates are a case in point, as the processing of verbal and nonverbal signs, i. e. the entire interaction, is shaped by the medium of TV (which operates in a certain market, in a certain political system and with certain journalistic norms). This medial shaping affects crucial conversational aspects like turn-taking, topic management, face work, portrayal of self and others and use of the studio space. Of course, these aspects are also shaped by genre and individual competence, but they all rely on the structural moments of the medium mentioned here. What we can observe here is a media- and genre-specific performance of verbal interaction, a phenomenon Tolson (2006: 10) called the “performativity” of media talk.

Political TV debates are also a good example of what has been referred to as the mediatization of politics (cf. Higgins 2018; Strömbeck/Esser 2014; Hepp 2014; Falasca 2014), i. e. the interdependency of the political and the mass-media systems, which results in the adaptation of the political system to the mass-media system and vice versa. As mentioned above, three different logics (journalistic, political and economic) shape the processing of signs in political TV debates as part of the institutional media context. In other words, political information is materialized and processed in a very specific, conversational way, including a specific use of multimodal resources (sensu Mondada 2016). In the following, we focus on aspects of medial shaping that can be related to structural moments of TV mediality and conversational TV formats.

2.1 Double Articulation and Para-interaction

All conversation on TV is double articulated, as Scannell argued in 1991:

All talk on radio and TV is public discourse, is meant to be accessible to the audience for whom it is intended. Thus broadcast talk minimally has a double articulation: it is a communicative interaction between those participating in discussion, interview, game show or whatever and, at the same time, is designed to be heard by absent audiences. (Scannell 1991: 1)

TV conversations are performed from the very beginning for a non-present, but always ratified audience. We therefore have to distinguish between the interaction between the interlocutors within the studio and the pseudo-interaction with the non-present audience. The latter has been described as “parasocial interaction” by Horton and Wohl (1956: 215), but we will instead refer to social para-interaction, because we understand all human relationships as “social” (cf. Moores 2005: 75). Para-interaction means that parts of the sign use provoke the illusion of face-to-face communication between persons in the studio and the audience at home, including mutual perception and two-way communication. Social para-interaction aims at “intimacy at a distance” (Horton/Wohl 1956: 215) and can be realized e. g. by addressing the audience or staging traits of informal face-to-face conversations. In our example, the audience is directly addressed at the beginning of the show (with a brief greeting, “Good evening”, and some explanation of the debate, “The people you see on this stage were chosen […]”) and again at the end of it (Cooper: “Our thanks to the candidates, the commission, Washington University, and to everybody who watched”, Raddatz: “Good night, everyone”); always accompanied by a look into the camera. Apart from these sequences, the audience at home is only once addressed verbally – and only implicitly and indirectly – by Clinton, in the following turn:

1. CLINTON: Well, Martha, first, let me say – and I’ve said before, but I’ll repeat it, because I want everyone to hear it – that was a mistake, and I take responsibility for using a personal e-mail account. (20:59–21:10, italics added)

Although it is clear – and with the greeting and goodbye it is made clear – that the conversation is directed at an audience at home, this fact remains marginalized throughout the debate in the verbal utterances. That – except for one camera tripod that appears briefly in one shot (1:30:50) – no cameras can be seen at any point in the debate also serves to deflect attention from the fact that the conversation is directed at an at-home audience. As such, then, direct hints at the presence of an audience at home are minimized.

At the same time, however, the gaze of the persons on the screen reveals an important aspect of social para-interaction. The politicians use gaze direction strategically: they mostly or at important moments look directly at the camera, and thus at the audience at home. While Trump looks into the camera most of the time when talking, Clinton mostly lets her gaze wander over the studio audience. But she looks straight into the camera at rhetorically key moments (see italics in the following excerpt, Example 2):

2. CLINTON: So this is who Donald Trump is. And the question for us, the question our country must answer is that this is not who we are. That’s why – to go back to your question – I want to send a message – we all should – to every boy and girl and, indeed, to the entire world that America already is great, but we are great because we are good, and we will respect one another, and we will work with one another, and we will celebrate our diversity. These are very important values to me, because this is the America that I know and love. And I can pledge to you tonight that this is the America that I will serve if I’m so fortunate enough to become your president. (10:13–11:02; italics added)

While Clinton generally looks at the audience in the studio or at Cooper, who asks her a question (see Screenshot 1), she looks into the camera during the sequences indicated above. This is not incidental, but clearly intended to address the audience at home with electoral promises (Screenshot 2; for similar observations, see Luginbühl 2017 and already Petter-Zimmer 1990).

Screenshots 1–2: Clinton answering a question

(10:15, 10:56)

This is one example of what we mean by medial shaping: an obviously patterned sign use (here the gaze) that deploys and is developed with the resources of a medial infrastructure (live broadcast over camera). This gaze is not exclusive to politicians in TV debates, or even to TV, so the form alone is not constitutive of the medium. But the form and the fact that it is a pattern can only be understood against the background of the medium: it is the specific technical possibilities (in a narrow sense) and the specific institutional interests and purposes (para-interaction with the voters at home) that lead to this sign use and shape gazing behavior.

A closer look at the candidates’ responses also shows other ways to double articulate answers. Because the main reason to take part in a political TV discussion is not to engage in an objective, rational debate, but to promote one’s own person and positions, politicians often switch the topic without verbally indicating that they are doing so, but instead phrasing the transition as if the two topics were related. Again, we have a form that is not specific to political TV debates but is intrinsically related to the medium of live TV debates with restricted time frames, politicians’ interest in self-promotion and the TV station’s interest in restricting that self-promotion and controlling the topics. Trump’s topic shifts are quite abrupt, integrated in an argumentative transition only very superficially, as in the following excerpt (Example 3).

3. TRUMP [responding to a question regarding some of his comments regarding women]: But this is locker-room talk. You know, when we have a world where you have ISIS chopping off heads, where you have – and, frankly, drowning people in steel cages, where you have wars and horrible, horrible sights all over, where you have so many bad things happening, this is like medieval times. We haven’t seen anything like this, the carnage all over the world. And they look and they see. Can you imagine the people that are, frankly, doing so well against us with ISIS? And they look at our country and they see what’s going on. Yes, I’m very embarrassed by it. I hate it. But it’s locker room talk, and it’s one of those things. I will knock the hell out of ISIS. (6:19–6:59)

Trump’s remarks about ISIS, which very roughly depict his plans if elected president, seem to be related to his response regarding his disrespectful comments about women. The phrasing “You know, when we have a world where …” allows us to expect argumentative support for his assessment of his utterances, but what follows is not related to this issue at all. While this topic shift is (even if only superficially) integrated, the next is not (Example 4).

4. COOPER: Have you ever done those things?

TRUMP: And women have respect for me. And I will tell you: No, I have not. And I will tell you that I’m going to make our country safe. We’re going to have borders in our country, which we don’t have now. People are pouring into our country, and they’re coming in from the Middle East and other places. We’re going to make America safe again. (7:36–7:54)

While the overall subject remains Trump’s behavior towards women, he starts discussing homeland security and “people” that are “pouring” into the country.

Although she is much more subtle, Clinton also sometimes employs this strategy. After Trump claims that Bill Clinton’s behavior towards women was much worse than his own, Clinton discusses Trump’s disrespectful treatment of Captain Humayun Khan. She skillfully and subtly leads to this new topic by accusing her opponent of “never apologiz[ing] for anything to anyone”, not even Khan (15:40–16:01). However, this argumentation cannot hide the fact that Clinton here also switches the topic.

All the aspects mentioned above – the direct or implicit addressing of the audience at home, the gaze behavior and the (more or less) inconspicuous topic shifts – are examples of double articulation. And they illustrate how structural aspects of the medium (one-way audiovisual mass medium, appropriation of public mass media by the political system) shape conversation practices. These practices show that all answers, and of course all questions too, are not for the audience in the studio, but the one at home. The scenario at stake is ‘technically’ contoured by the medial procedure, but it is not constituted by it alone. At the same time, of course, our understanding of the whole scenario is just as much a question of the semiotic construction of meaning, the staging in the language game presidential debate and the individual competence of the protagonists: who, for example, makes the most clever use of the latitudes of double articulation?

2.2 Controlling and Spurring the Debate: The Town-hall Framing

The aspects discussed in this section are second-order media effects: the medium of television (as an institution and procedure) aims to create and maintain a social relationship with its audience. Aspects of this “sociability” (Scannell 1996: 28) include the staging of being close to the audience (see above, para-interaction, but also close shots, live broadcasting and so on), the stating of spontaneous behavior and of course the meta-function of television, entertainment. The aim of television companies is to produce an entertaining (which does not necessarily mean un-informative) debate, a dynamic swapping of blows between the candidates. This means that there must be critical questions and not just keywords that allow the candidates to articulate their slogans (cf. Clayman/Heritage 2002). At the same time, however, the debate must be controlled by the medium’s agents, the hosts, so that it does not descend into chaos.

The ways in which this debate is framed and the ways in which the hosts vary between sparking off and controlling the debate reveal how the institutional aims of the medium shape conversational action at the level of the communicative practices common to political TV debates, including asking questions, providing answers, assigning the right to speak, turn-taking in general, real-time processing of utterances and face work. These essential aspects of face-to-face (or side-by-side) interaction and the political TV debate genre are interwoven with the mediality of the debate, because the communicative practices common in this genre are shaped by, on the one hand, the institutional aspects of and politics within TV and, on the other, the semiotic resources provided by the medium. Of course, this does not mean that the mediality determines everything: it is, as already mentioned, a necessary but not sufficient condition of communication. A presidential debate is an example of a highly staged language game with explicit and implicit rules whose non-compliance is sanctioned. And the competence of the players, their ability to deal with semiotic resources, is also crucially important for the course and outcome of the game.

The debate is framed as a “town-hall meeting” (COOPER: “Tonight’s debate is a town-hall format, which gives voters the chance to directly ask the candidates questions”[7]). This framing as a town-hall meeting that is open to everyone and makes it possible to ask critical questions “directly” is related to the journalistic norm of serving as the fourth estate, because the journalists appear as agents of control by bringing the citizens’ questions to the candidates. But while the frame of a town-hall meeting implies that everyone can spontaneously pose as many questions as they like and the person interviewed can answer in detail, the conversation here is strongly controlled by regulations set by the media institution and the actions of the medium’s representatives, the hosts: the speaking time for an answer is limited to two minutes; the citizens in the inner circle of the studio are hand-picked and prevented from engaging in any backchannel behavior, whether verbal or non-verbal (an obvious transformation of everyday practices) and from asking follow-up questions; and the studio audience in the outer circle, which cannot be seen but can sometimes be heard and is then silenced by the hosts, is also subject to strict rules (COOPER: “We want to remind the audience to please not talk out loud. Please do not applaud. You’re just wasting time”. 20:30; RADDATZ: “And really, the audience needs to calm down here”. 19:39). This control is related to the journalistic principle of balance, but it is of course also intended to control the candidates’ self-promotion and the possible escalation of the interaction.

In some of these cases, we can see how the hosts use the town-hall frame to control the conversation explicitly: they use it to manage the timing and the topics discussed. Timing is crucial for all media talk, as the conversations cannot, unlike in an actual town hall, be open-ended, but have to end right on time. This allows the hosts to interrupt the candidates by referring to the citizens’ questions (already at the very beginning, the host Raddatz says: “[…] we hope to get to as many questions as we can. So we asked the audience here not to slow things down with any applause […]”). In the following extract (00:11:04–12:11), Raddatz interrupts Trump, who is responding to accusations from Clinton (“I said starting back in June that he was not fit to be president and commander-in-chief” 8:39):

5. RADDATZ: And we want to get to some questions from online

TRUMP: Am I allowed to respond to that? I assume I am.

RADDATZ: Yes, you can respond to that.

TRUMP: It’s just words, folks. It’s just words. Those words, I’ve been hearing them for many years. I heard them when they were running for the Senate in New York, where Hillary was going to bring back jobs to Upstate New York and she failed. I’ve heard them where Hillary is constantly talking about the inner cities of our country, which are a disaster education-wise, jobwise, safety-wise, in every way possible. I’m going to help the African-Americans. I’m going to help the Latinos, Hispanics. I am going to help the inner cities. She’s done a terrible job for the African-Americans. She wants their vote, and she does nothing, and then she comes back four years later. We saw that firsthand when she was United States senator. She campaigned where the primary part of her campaign…

RADDATZ: Mr. Trump, Mr. Trump – I want to get to audience questions and online questions.

TRUMP: So, she’s allowed to do that, but I’m not allowed to respond?

RADDATZ: You’re going to have – you’re going to get to respond right now.

TRUMP: Sounds fair.

RADDATZ: This tape is generating intense interest. […]

The questions from the live audience and television viewers are not asked at the initiative of the audience members themselves or when the candidates indicate that they are finished answering the previous question, but when the hosts decide; in addition, audience members cannot ask for further clarifications after asking their question. Referring to audience questions also allows the hosts to ask face-threatening questions and at the same time “deflect” them (cf. Clayman/Heritage 2002), i. e. the hosts can bring up critical issues without having to affiliate or disaffiliate themselves from them (RADDATZ: “So, Tu from Virginia asks: is it OK for politicians to be two-faced?” 43:49).

The hosts perform a tightrope walk between a controlled, answer-question interview and a dynamic quarrel between the candidates. For example, if one candidate provokes the other, the hosts may depart from the question-answer structure. While the overall structure follows the order ‘question – answer candidate 1 – answer candidate 2’, in Example 5 above Trump successfully demands the floor again after Clinton responds to his first answer and attacks him directly (not in transcript). The hosts suspend the regular order here to follow the provocation principle: guests who are provoked get the turn. Nonetheless, Raddatz interrupts Trump after one minute because he does not address the question that has been posed, but instead delivers slogans and demeans Clinton. When he is interrupted, he insists on the provocation principle mentioned above (“So she’s allowed to do that, but I’m not allowed to respond?”). In the next example, he also insists on being permitted to respond after Clinton has responded to a question that was directed only to her; in doing so, he refers to the right to equal speaking time, a phenomenon specific to political TV debates (Example 6, 00:41:57–42:04):

6. RADDATZ: There’s been lots of fact-checking on that. I’d like to move on to an online question…

TRUMP: Excuse me. She just went about 25 seconds over her time.

RADDATZ: She did not.

TRUMP: Could I just respond to this, please?

RADDATZ: Very quickly, please.

Situations like these, which are aimed at controlling the debate, often lead to fights for the floor among the candidates and between the candidates and the hosts. At such moments, the subject is often abandoned quickly, mutual denials are exchanged and more complex arguments cannot be elaborated. But the audience can witness a highly dynamic verbal fight that could become chaotic, and which the hosts must therefore contain. Such situations have a high entertainment potential and thus contribute to sociability, as the following excerpt demonstrates (Example 8, 00:23:37–24:33):

7. TRUMP: […] What you did – and this is after getting a subpoena from the United States Congress.

COOPER: We have to move on.

TRUMP: You did that. Wait a minute. One second.

COOPER: Secretary Clinton, you can respond, and then we got to move on.

RADDATZ: We want to give the audience a chance.

TRUMP: If you did that in the private sector, you’d be put in jail, let alone after getting a subpoena from the United States Congress.

COOPER: Secretary Clinton, you can respond. Then we have to move on to an audience question.

CLINTON: Look, it’s just not true. And so please, go to…

TRUMP: Oh, you didn’t delete them?

COOPER: Allow her to respond, please.

CLINTON: It was personal e–mails, not official.

TRUMP: Oh, 33,000? Yeah.

CLINTON: Not – well, we turned over 35,000, so…

TRUMP: Oh, yeah. What about the other 15,000?

COOPER: Please allow her to respond. She didn’t talk while you talked.

CLINTON: Yes, that’s true, I didn’t.

TRUMP: Because you have nothing to say.

CLINTON: I didn’t in the first debate, and I’m going to try not to in this debate, because I’d like to get to the questions that the people have brought here tonight to talk to us about.

TRUMP: Get off this question.

CLINTON: OK, Donald. I know you’re into big diversion tonight, anything to avoid talking about your campaign and the way it’s exploding and the way Republicans are leaving you. But let’s at least focus…

TRUMP: Let’s see what happens…

In this example, Clinton can hardly respond coherently because Trump keeps interrupting her; in addition, the host repeatedly tries to save the floor for Clinton. She accuses Trump of diversion, i. e. strategic behavior, and attempts to control the debate herself by suggesting that they move on to the audience’s questions. Trump in turn accuses the hosts of neglecting the Clinton e-mail controversy, an accusation Cooper rejects repeatedly before giving the floor to an audience member, causing Trump to utter an ironic remark in which he frames the debate as an unfair fight (“one on three”).

Sequences like these are predictable in political TV debates and are not a result of the specific combination of individuals involved here, but genre-specific practices (cf. Luginbühl 1999; 2007). While the politicians try to get as much speaking time as possible in order to promote themselves and devaluate their opponent, the hosts both spur the debate and try to control it in order to combine the medium’s institutional needs for entertainment and balance. Sequences like these are predictable because they are structural moments of TV communication in general (double articulation, para-interaction, sociability) and political communication in and for TV in particular (mediatization of politics, different logics at work). Aspects of everyday talk like turn-taking, topic management, portrayal of self and others and face and relational work are shaped (but not constituted) by these media-specific aspects from the very beginning – and not just because they are filmed and aired. The same is true of the town-hall frame: it is optimized for the needs of the medium in order to simultaneously stage a democratic discussion and control the interaction.

2.3 Camerawork and Editing

Nonverbal behavior is also shaped by the medium. We have already mentioned the strategic use of gazing at the camera (i. e. directly at the audience at home). But while politicians can control their nonverbal behavior to some extent, they cannot control which camera perspective is used or how the footage is edited, and their behavior in space is also restricted by the studio design. Final control over the audio-visual text that is broadcast therefore lies with the medium – that is, with the media institution’s picture director (cf. Holly 2015). The design of the studio and especially the way the footage is edited shape and contextualize what is said and how the participants (can) use their bodies – and what we can see of this. What we can see and hear is not just a combination of sound and images, but an independent staging of the course of conversation (cf. Keppler 2015: 171). What is most striking in NBC’s coverage of the second debate is the predominant use of split screens: of the 68 minutes that the debate lasts, 49:35 consist of split-screen shots in which the two candidates can be seen in close-up. The studio design is obviously optimized for these split screens (Screenshot 3).

Screenshot 3: studio design (0:00).

The two chairs do not face each other or the studio audience (the “town-hall participants”), but the hosts. The cameras are placed to deliver a full frontal view of the candidates: they are located to the left and right of the hosts (note that the chairs actually face the cameras, not the hosts) and (hidden in black windows and thus hardly visible) behind the “town-hall participants”. The room, with its spatial arrangement of hosts, participants and bar stools, and its camera infrastructure, predetermines how the candidates will move, but without prescribing specific movements (cf. Hausendorf 2020). To sum up, the entire room is unobtrusively and invisibly optimized for full-frontal camera shots of the candidates and for staging a town-hall meeting. In addition, the cameras behind the participants allow for medium shots that show both candidates at the same time, one behind the other. This studio design is directly related to the institutional goals of the medium and thus to structural moments of the medium as we understand it. The sign systems made available and their semiotically indicated use are related to the institution’s goals, and as we will show this shapes the ways in which signs are processed within the genre and within the individual competences of the interactants. Again, the optimization of the medial infrastructure for the media’s institutional goals does not determine the sign use, but it does shape communicative practices.

As mentioned above, the predominant camera setting is the split screen (see Screenshot 4).

Screenshot 4: split screen (5:15).

The split screen allows for two frontal close shots at the same time, which makes it possible for the home audience to sit very close to both candidates simultaneously and observe even the smallest mimic movements, allowing it to scrutinize the emotional reactions of the speaker and listener at the same time. It is important to note that this is an ‘impossible’ view, as the screenshot below (Screenshot 5) demonstrates: immediately before Screenshot 4, we can see that, from a viewer’s perspective on site, it is impossible to see both candidates from the front; and we can also see that they do not have their heads at the same height, contrary to what the split screens suggests.

Screenshot 5: split screen (4:59).

We can see here how medial procedures create a reality of their own. A possible attraction of these debates, as mentioned above, is the tightrope walk between control and (conversational) chaos, which also foregrounds face and relational work. And it is these aspects that the split screen, with its frontal view of both candidates’ faces, also emphasizes. In contrast to a switched feed, a split screen also allows the audience to see minimal nonverbal reactions at all times, and not just during reaction shots. Direct reaction shots at more or less predictable points would grant the politicians more control over the situation. But in a split screen any action can be interpreted as a reaction, which usually leads to very reduced and limited backchannel behavior, both verbally and nonverbally. It is therefore not surprising that split screens and switched feeds affect reception differently (see Stewart et al. 2017; Wicks et al. 2017). But the use of split screens can also lead to orientation problems on the part of the audience: because the front view is predominant, it can become unclear who the candidates are looking or pointing at.

Together, Example 8 above and Screenshots 6 and 7 below illustrate how the split screen works. While Trump continues to attack Clinton, she smiles broadly, which she rarely does in the entire debate, and shakes her head.

Screenshot 6: Clinton smiling and shaking head while Trump attacks (23:41).

A few seconds later, a four-second shot demonstrates that the split screen showed an ‘impossible’ view that a person on location could not have had (Screenshot 7).

Screenshot 7: Clinton responding to Trump’s attacks (23:48).

If only the person talking, in this case Trump, had been shown, Clinton’s nonverbal behavior could not have been seen, just as it would have been difficult to see it in the studio. Since the two protagonists are well briefed, they know that the split-screen format predominates, and they expect to be filmed in close-up even when they are not speaking. When she is not speaking, Clinton tries to avoid looking into the camera; in some cases, however, she does glance at the camera before immediately turning her gaze away (37:20–37:38). This is another example of how the media process contours and influences the actors’ communicative actions. We can see here how the camerawork creates a media-specific reality that is intended to allow viewers to witness emotional (or strikingly calm) reactions to attacks. In the end, it is all about who cracks whom.

Although the split screen predominates, reporting on the debate focused extensively on shots during which Trump could be seen behind Clinton. Immediately after the debate, for example, the Guardian published in its online version a short video excerpt from the debate entitled “Trump ‘prowls’ behind Clinton during presidential debate” (Guardian 2016). CNN commented as follows: “Donald Trump created an awkward situation during Sunday’s presidential debate, where the candidates were free to roam around the stage, and the Republican nominee chose to stand right behind Hillary Clinton” (Diaz 2016). Clinton herself wrote afterwards: “It was the second presidential debate and Donald Trump was looming behind me” (Filipovic 2016). And New York Times journalist David Itskoff (2016) created the following meme (Tweet 1):

Tweet 1: Tweet by David Itskoff.

Two things are noteworthy about these shots in which one candidate can be seen behind the other. First, these shots comprise only 16 minutes of the debate (compared to almost 50 minutes of split screen); and second, of these 16 minutes, shots of Trump behind Clinton comprise 11:21, while those of Clinton behind Trump comprise only 4:56. Trump’s “looming behind” Clinton is a result of not only the fact that he is shown doing this twice as much as she is, but also that Trump moves behind Clinton when she speaks, while she does not move very much when he speaks.

The following screenshots show Clinton moving towards the right to answer an audience question from that side of the studio, and Trump moving back to his chair but then positioning himself directly in sight of the camera that is filming Clinton (Screenshots 8–10).

Screenshot 8–10: Trump aligning himself behind Clinton (25:25–25:50).

We can see here how politicians and the medium (as an institution) interact at the micro-level: Trump strategically aligns himself with the camera’s line of sight, and the camera cuts from a close to a medium shot, including both candidates in one frame, again allowing both faces to be seen at the same time. When Trump positions himself in a spot that is likely (but not necessarily) to be captured by the camera, the image immediately cuts to capture that view. As a result, CNN’s claim that Trump “created” this situation is only half true.

The camera also attempts to capture Clinton in the background while Trump is speaking but not looking in the direction of the hosts; but – and this is the difference – Clinton does not align her body with the camera, but only her gaze (see Screenshots 11–12).

Screenshot 11–12: Clinton behind Trump (29:14; 33:39).

The candidates’ gaze work, the way they use the studio room, how they walk, align and disalign their bodies are all shaped by the medium of television. As in language use, the effect of the medium is not secondary. The medium itself influences the behavior of the persons on screen from the outset and creates its own reality of the conversation, a reality that cannot be experienced at the location itself. As well, the ways in which the protagonists of the language game presidential debate use semiotic resources to construct meaning and exploit the latitudes of media staging are once again centrally important. Our example demonstrates that the four aspects mentioned above in Figure 1 can and must be differentiated in an analysis, but also that they interact. The medium (live TV combining the institutional interests of TV stations and politicians) determines the semiotic modes and medial infrastructure that can be deployed (spoken and written language, moving film with camera work, film editing, nonverbal communication and so on). On the basis of these semiotic modes and medial infrastructure and communicative needs, genres emerge, are passed on or change (in our case political TV debate with specifics regarding conversational behavior, nonverbal behavior, film editing, camera work and so on). At the same time, a communicative practice is always co-dependent on individual abilities.

3. Conclusion

As the analysis of the second presidential debate between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump has shown, sign processing during the debate is permeated by structural aspects of television and specific traits of political communication in television. These structural aspects – the technical infrastructure, para-interaction, entertainment, the fourth estate, political propaganda and so on – can potentially conflict with each other, which leads to, and is exploited by, specific practices on the part of the hosts, the politicians and the studio audience. The way oral communication is processed (including embodied aspects) is therefore shaped by the whole medial procedure from the outset, including the ways in which turn-taking is organized, topics are introduced and avoided, face work is done and controversies are cheered on or ended, and where people move or look.

Therefore, it is not adequate to separate the technical aspects of the medium – the ‘hardware’ and the materiality – from the structural conditions of communication and other processual aspects. All these aspects belong to the mediality of a medium, i. e. of a medial procedure. As we have argued, what German media linguists call “communication form” is also included in the medial procedure. If we separate these aspects from each other, it is impossible to adequately analyze the “medial traces” (cf. Krämer 1998) they leave behind. A holistic concept of media, as we propose it here, makes it possible to better understand the medial shaping of human communication, but it must of course be defined more finely and systematically in future studies.

The most important task of media linguistics is to describe communication as consisting of medial procedures of a specific granularity under concrete circumstances. What is the mediality of a given medial constellation and format? Another task of media linguistics is to differentiate the mediality of a concrete case from the communicative, culturally constituted practices involved. Mediality also has institutional aspects. A third task of media linguistics is to distinguish between the institutional and other aspects that are constitutive of communicative practices. Making these distinctions will help us understand our communication better and differentiate medial constellations, and they provide a very specific and clear role for what we call media linguistics.

References

Auer, Peter (2009): On-line syntax: Thoughts on the temporality of spoken language. In: Language Sciences 31 (1), 1–13.

Austin, John L. (1975): How To Do Things With Words. Second edition. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Bateman, John/Wildfeuer, Janina/Hiippala, Tuomo (2017): Multimodality: Foundations, Research and Analysis. A Problem-Oriented Introduction. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Becker-Mrotzek, Michael (2009): Mündliche Kommunikationskompetenz. In: Becker-Mrotzek, Michael (ed.): Mündliche Kommunikation und Gesprächsdidaktik. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren, 66–83.

Bolter, Jay D./Grusin, Richard (2002): Remediation. Understanding New Media. Fifth edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Brinker, Klaus (2005): Linguistische Textanalyse. Eine Einführung in Grundbegriffe und Methoden. Berlin: Erich Schmidt.

Brock, Alexander/Schildhauer, Peter (eds.) (2017a): Communication Forms and Communicative Practices. New Perspectives on Communication Forms, Affordances and What Users Make of Them. Bern/Berlin: Peter Lang.

Brock, Alexander/Schildhauer, Peter (2017b): Communication Form: A Concept Revisited. In: Brock, Alexander/Schildhauer, Peter (eds.): Communication Forms and Communicative Practices. New Perspectives on Communication Forms, Affordances and What Users Make of Them. Bern/Berlin: Peter Lang, 13–43.

Bucher, Hans Jürgen (2007): Logik der Politik – Logik der Medien. Zur interaktionalen Rhetorik der politischen Kommunikation in den TV-Duellen der Bundestagswahlkämpfe 2002 und 2005. In: Habscheid, Stephan/Klemm, Michael (eds.): Sprachhandeln und Medienstrukturen in der politischen Kommunikation. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 13–44.

Clayman, Steven/Heritage, John C. (2002): The news interview: Journalists and public figures on the air. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cook, Timothy E. (1998): Governing with U1e news: The news media as a political institution. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Cook, Timothy E. (2006): The News Media as a Political Institution: Looking Backward and Looking Forward. In: Political Communication 23 (2), 159–171.

Dang-Anh, Mark (2019): Protest twittern. Eine medienlinguistische Untersuchung von Strassenprotesten. Bielefeld: transcript.

Denton, Robert E. (ed.) (2017): Studies of Communication in the 2016 Presidential Campaign. New York: Lexington.

Diaz, Daniella (2016): Trump looms behind Clinton at the debate. URL: https://edition.cnn.com/2016/10/09/politics/donald-trump-looming-hillary-clinton-presidential-debate/index.html.

Fairclough, Norman (1995): Media Discourse. London: Arnold.

Falasca, Kajsa (2014): Political news journalism: Mediatization across three news reporting contexts. In: European Journal of Communication 29 (5), 583–597.

Filipovic, Jill (2016): Donald Was a Creep. Too Bad Hillary Couldn’t Say It. In: New York Times online, August 24, 2016, URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/24/opinion/sunday/donald-was-a-creep-too-bad-hillary-couldnt-say-it.html.

Fiske, John (1987): Television culture: popular pleasures and politics. London/New York: Methuen.

Gans, Herbert J. (1979): Deciding what's news: A study of CBS evening news, NBS nigthly news, Newsweek and Time. New York: Pantheon.

Granados, Nelson (2016): Millions Watch Second Presidential Debate On Illegal Streams. In: Forbes online, October 10, 2016. URL: https://www.forbes.com/sites/nelsongranados/2016/10/10/millions-watched-illegal-streams-of-second-presidential-debate/#3ecce01a58a0.

Greatbatch, David (1998): Conversation Analysis: Neutralism in British News Interviews. In: Bell, Allan/Garrett, Peter (eds.): Approaches to media discourse. Oxford: Blackwell, 163–185.

Guardian (2016): Trump ‘prowls’ behind Clinton during presidential debate. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/video/2016/oct/10/donald-trump-behind-hillary-clinton-debate-video.

Gutenberg, Norbert (2001): Einführung in Sprechwissenschaft und Sprecherziehung. Frankfurt a. M.: Lang.

Hanitzsch, Thomas (2007): Deconstructing Journalism Culture: Towards a universal theory. In: Communication Theory 17 (4), 367–385.

Hartley, John (1982): Understanding News. London: Methuen.

Hartley, John (2020): Communication, cultural and media studies. The key concepts. Fifth edition. London/New York: Routledge.

Hartley, John/Montgomery, Martin (1985): Representations and Relations: Ideology and Power in Press and TV News. In: Van Dijk, Teun A. (ed.): Discourse and Communication: New Approaches to the Analysis of Mass Media Discourse and Communication. Berlin: de Gruyter, 233–269.

Hausendorf, Heiko (2020): Die Betretbarkeit der Institution – ein vernachlässigter Aspekt der Interaktion in Organisationen. In: Gruber, Helmut/Spitzmüller, Jürgen/de Cillia, Rudolf (eds.): Institutionelle und organisationale Kommunikation. Theorie, Methodologie, Empirie und Kritik. Kommunikation im Fokus. Wien: V&R, 119–148.

Hepp, Andreas (2014): Mediatization. A panorama of media and communication research. In: Androutsopoulos, Jannis (ed.): Mediatization and sociolinguistic change. Berlin: de Gruyter, 49–66.

Hermanns, Fritz (2012): Sprache, Kultur und Identität. In: Kämper, Heidrun/Linke, Angelika/Wengeler, Martin (eds.): Der Sitz der Sprache im Leben. Beiträge zu einer kulturanalytischen Linguistik. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 235–276.

Higgins, Michael (2018): Mediatisation and political language. In: Wodak, Ruth/ Forchtner, Bernhard (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Language and Politics. London: Routledge, 383–397.

Holly, Werner (2004): Fernsehen. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Holly, Werner/Kühn, Peter/Püschel, Ulrich (1986): Politische Fernsehdiskussionen. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Holly, Werner/Kühn, Peter/Püschel, Ulrich (eds.) (1989): Redeshows. Zur medienspezifischen Inszenierung von Propaganda als Diskussion. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Holly, Werner (2015): Bildinszenierungen in Talkshows. Medienlinguistische Anmerkungen zu einer Form von „Bild-Sprach-Transkription“. In: Girnth, Heiko/Michel, Sascha (eds.): Polit-Talkshow. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf ein multimodales Format. Stuttgart: ibidem, 123–144.

Horton, Donald / Wohl, Richard R. (1956): Mass Communication and Para-social Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance. In: Psychiatry 19, S. 215-229.

Hutchby, Ian (2014): Communicative affordances and participation frameworks in mediated interaction. In: Journal of Pragmatics 72, 86–89.

Imo, Wolfgang/Lanwer, Jens Philipp (2019): Interaktionale Linguistik. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.

Itskoff, David (dizkoff) (2016): “This looks like a poster for a 1970s horror movie.” 10 October 2016, 3:32 a.m. Tweet. URL: https://twitter.com/ditzkoff/status/785291824273428480.

Jäger, Ludwig (2004): Wieviel Sprache braucht der Geist? Mediale Konstitutionsbedingungen des Mentalen. In: Jäger, Ludwig/Linz, Erika (eds.): Medialität und Mentalität. Theoretische und empirische Studien zum Verhältnis von Sprache, Subjektivität und Kognition. München: Fink, 15–42.

Jäger, Ludwig (2010): Ferdinand de Saussure zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius.

Jäger, Ludwig (2012): Transkription. In: Bartz, Christina/Jäger, Ludwig/Krause, Marcus/Linz, Erika (eds.): Handbuch der Mediologie. Signaturen des Medialen. München: Fink, 306–315.

Jäger, Ludwig (2015): Medialität. In: Felder, Ekkehard/Gardt, Andreas (eds.): Handbuch Sprache und Wissen. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 106–122.

Jucker, Andreas H. (1986): News Interviews. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Keppler, Angela (2015): Das Gesagte und das Nichtgesagte. Was die Dramaturgie politischer Talkshows zeigt. In: Girnth, Heiko/Michel, Sascha (eds.): Polit–Talkshow. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf ein multimodales Format. Stuttgart: ibidem, 169-188.

Krämer, Sybille (1998): Das Medium als Spur und als Apparat. In: Krämer, Sybille (ed.): Medien, Computer, Realität. Wirklichkeitsvorstellungen und Neue Medien. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 73–94.

Krebs, Christina (2007): Die Kanzlerduelle im Fokus der Linguistik: Selbstdarstellung und Beziehungsgestaltung in medialen Streitgesprächen. Saarbrücken: VDM.

Lagaay, Alice/Lauer, David (2004): Einleitung – Medientheorien aus philosophischer Sicht. In: Lagaay, Alice/Lauer, David (eds.): Medientheorien. Eine philosophische Einführung. Frankfurt a. M./ New York: Campus, 7–29.

Leeuwis, Cees (2004): Communication for Rural Innovation. Rethinking Agricultural Extension. Third edition. Oxford: Blackwell Science. URL: http://www.modares.ac.ir/uploads/Agr.Oth.Lib.8.pdf.

Linz, Erika (2016): Sprache, Materialität, Medialität. In: Jäger, Ludwig/Holly, Werner/Krapp, Peter/Weber, Samuel/Heekeren, Simone (eds.): Sprache – Kultur – Kommunikation. Ein internationales Handbuch zu Linguistik als Kulturwissenschaft. Berlin/ Boston, 100–111.

Luginbühl, Martin (1999): Gewalt im Gespräch. Verbale Gewalt in politischen Fernsehdiskussionen am Beispiel der "Arena". Bern: Lang.

Luginbühl, Martin (2007): Conversational violence in political TV debates: Forms and functions. In: Journal of Pragmatics 39 (8), 1371–1387.

Luginbühl, Martin (2015): Media linguistics. On Mediality and Culturality. In: 10plus1. Living Linguistics 1, 9-26. URL: http://10plus1journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/00_OPENER_Luginbuehl.pdf.

Luginbühl, Martin (2017): Massenmedien als Handlungsfeld II: audiovisuelle Medien. In: Roth, Kersten S./Wengeler, Martin/Ziem, Alexander (eds.): Handbuch Sprache in Politik und Gesellschaft. Berlin: de Gruyter, 334–353.

Luginbühl, Martin (2019): Mediale Durchformung: Fernsehinteraktion und Fernsehmündlichkeit in Gesprächen im Fernsehen. In: Marx, Konstanze/Schmidt, Axel (eds.): Interaktion und Medien. Interaktionsanalytische Zugänge zu medienvermittelter Kommunikation. Heidelberg: Winter, 125–146.

Margreiter, Reinhard (2001): Wissenskonstitution im Spannungsfeld von Arbeit, Spiel und Medien. URL: http://www2.uibk.ac.at/wiwiwi/home/tagung/ margreiter.pdf.

Margreiter, Reinhard (2003): Medien/Philosophie: Ein Kippbild. In: Münker, Stefan/Roesler, Alexander/Sandbothe, Mike (eds.): Medienphilosophie. Beiträge zur Klärung eines Begriffs. Frankfurt a. M.: Fischer, 150–171.

Marx, Konstanze/Weidacher, Georg (2014): Internetlinguistik: Ein Lehr- und Arbeitsbuch. Tübingen: Narr.

McLuhan, Marshall (1964): Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

McLuhan, Marshall/Fiore, Quentin ([1967] 2001): The medium is the message. An inventory of effects. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press.

Meiler, Matthias (2018): Eristisches Handeln in wissenschaftlichen Weblogs. Medienlinguistische Grundlagen und Analysen. Heidelberg: Synchron (= Wissenschaftskommunikation, 12).

Merriam-Webster online. URL: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/technique.

Mondada, Lorenza (2016): Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. In: Journal of Sociolinguistics 20 (3), 336–366.

Moores, Shaun (2005): Media/theory: Thinking about media and communications. London: Routledge.

Morley, David (1992): Television, Audiences and Cultural Studies. London/New York: Routledge.

Münker, Stefan (2008): Was ist ein Medium? Ein philosophischer Beitrag in einer medientheoretischen Debatte. In: Münker, Stefan/Roesler, Alexander (eds.): Was ist ein Medium? Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 322–337.

Münker, Stefan (2013): Media in use. How the practice shapes the mediality of media. In: Distinktion. Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory 14 (3), 246–253.

Münker, Stefan/Roesler, Alexander (2008): Vorwort. In: Münker, Stefan/Roesler, Alexander (eds.): Was ist ein Medium? Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 7–12.

Packard, Stephan/Rauscher, Andreas/Sian, Véronique/Thon, Jan-Noël/Wilde, Lukas R.A./Wildfeuer, Janina (2019): Comicanalyse. Eine Einführung. Berlin: Metzler.

Petter-Zimmer, Yvonne (1990): Politische Fernsehdiskussionen und ihre Adressaten. Tübingen: Narr.

Ryfe, David M. (2006): Guest editor's introduction: New institutionalism and the news. In: Political Communication 23 (2), 135–144.

Sandbothe, Mike (2001): Pragmatische Medienphilosophie. Grundlegung einer neuen Disziplin im Zeitalter des Internet. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

Saussure, Ferdinand de (1967): Cours de linguistique générale. Edition critique par Rudolf Engler. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Saussure, Ferdinand de (1972): Cours de linguistique générale. Edition critique preparé par Tullio de Mauro. Paris: Payot.

Scannell, Paddy (1991): Introduction. The relevance of talk. – In: Scannel, Paddy (ed.): Broadcast Talk. London: Sage, 1-13.

Scannell, Paddy (1996): Radio, Television and Modern Life. A Phenomenological Approach. Oxford: Blackwell.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1988): From interviews to confrontation: observations of the Bush/Rather encounter. In: Research on Language and Social Interaction 22, 215 – 240.

Schmitz, Ulrich (2015): Einführung in die Medienlinguistik. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Schneider, Jan Georg (2006): Language and mediality. On the medial status of 'everyday language'. In: Language & Communication 26 (3-4), 331–342.

Schneider, Jan Georg (2008): Spielräume der Medialität. Linguistische Gegenstandskonstitution aus medientheoretischer und pragmatischer Perspektive. Berlin/New York: de Gruyter.

Schneider, Jan Georg (2017): Medien als Verfahren der Zeichenprozessierung. Grundsätzliche Überlegungen zum Medienbegriff und ihre Relevanz für die Gesprächsforschung. In: Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 18 (2017), 34–55. URL: http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2017/ga-schneider.pdf.

Schroeder, Alan (2000): Presidential Debates: Forty Years of High Risk Television. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schudson, Michael (2003): The sociology of news. New York: Norton.

Schudson, Michael (2018): Why journalism still matters. Cambridge: Polity.

Schwitalla, Johannes (1979): Dialogsteuerung in Interviews. Ansätze zu einer Theorie der Dialogsteuerung mit empirischen Untersuchungen von Politiker-, Experten- und Starinterviews im Rundfunk und Fernsehen. München: Hueber.

Serjeant, Jill/Richwine, Lisa (2016): TV audience sharply down for second Trump-Clinton debate, despite tape furor. URL: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-debate-ratings/tv-audience-sharply-down-for-second-trump-clinton-debate-despite-tape-furor-idUSKCN12A1LF.

Shoemaker, Pamela J./Reese, Stephen D. (2014): Mediating the Message in the 21st Century. New York: Routledge.

Silverblatt, Art (2004): Media as social institution. In: American Behavioral Scientist 48 (1), 35–41.

Sparrow, Barholomew H. (1999): Uncertain guardians. The news media as political institutions. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Stetter, Christian (2005): System und Performanz. Symboltheoretische Grundlagen von Medientheorie und Sprachwissenschaft. Weilerswist: Velbrück Wissenschaft.

Stewart, Patrick A./Eubanks, Austin D.7Dye, Reagan G./Eidelman, Scott/Wicks, Robert H. (2017): Visual Presentation Style 2: Influences on Perceptions of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton Based on Visual Presentation Style During the Third 2016 Presidential Debate. In: American Behavioral Scientist 61 (5), 545–557.